January 31, 1939: I’m looking for someone, to whom I could tell my worries and joys of everyday life. From today on, we start a very hearty friendship. Who knows how long it will last?

July 28, 1942: Hear O Israel, save us, help us! You have kept me safe from bullets and bombs, from grenades, help me to survive, help us!

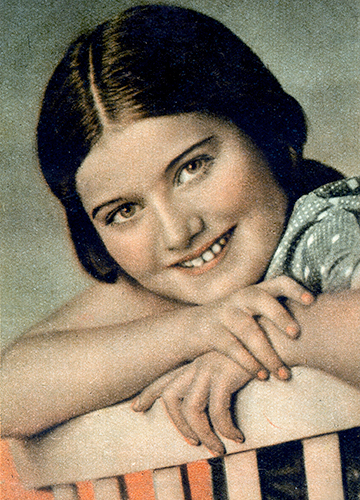

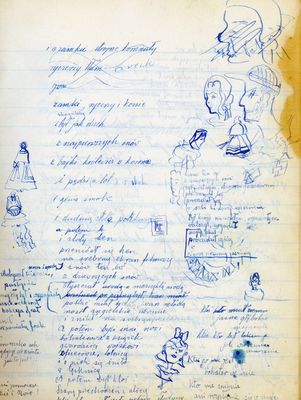

Between the first and last entry in her tattered, blue-lined diary, Polish teenager Renia Spiegel saw life blossom and wither. When 15-year-old Renia sat down to pour out her adolescent struggles into a diary, it is unlikely she anticipated the terror that would flood its pages. The ‘hearty friendship’ lasted a little more than three years. Two days after the entry on July 28, 1942, she was shot to death by Nazis who found her hiding place. She was Jewish.

Nearly 80 years later, the diary, with over 600 pages of prose and poetry, is being hailed as a moving piece of Holocaust literature. Renia’s Diary: A Young Girl’s Life in the Shadow of the Holocaust will be released by Penguin Random House on September 24 in the United States. In the UK, the book is being published by St Martin’s Press. In 1950, Renia’s diary was delivered to her mother and sister Ariana (who now goes by the name Elizabeth Bellak) in New York by Renia’s boyfriend Zygmunt Schwarzer who survived the war. It still remains a mystery how the diary made its way safely out of Poland.

“It was extremely painful for me to read the diary. It still is; I get palpitations,” 88-year-old Elizabeth tells THE WEEK, as she explains why it was locked away in a bank vault all these years. Had it not been for Elizabeth’s daughter Alexandra Bellak, a New York-based real estate agent, the book would still be lying untouched in the vault.

“The stories about my mother’s past were always difficult to discuss. I knew this diary existed and I thought I could discover more about Renia and my own past,” says Alexandra, who got in touch with a graduate student in Poland about eight years ago, and paid him to translate it into English. “And then I realised this had a historic significance.”

Elizabeth and Renia’s life took a turn for the worse in the summer of 1939 when Poland was invaded by the Germans and the Russians. The sisters, who were staying at their grandparents’ home in Przemysl, got stranded on the Nazi side. Their mother Roza was in Warsaw, which fell to the Soviets. The girls remained separated from their mother for almost two years. At one point, the girls and their grandparents were captured and pushed into a ghetto. Zygmunt, who was active in the resistance movement, managed to get them out, recalls Elizabeth. While Renia went into hiding with Zygmunt’s parents in the attic of a house, he put Elizabeth with a Christian friend’s father who helped reunite her with their mother in Warsaw in 1942. Meanwhile, the Germans killed Zygmunt’s parents and Renia. An anguished Zygmunt, who had held on to Renia’s diary, wrote the last entry after he lost the three most important people in his life: “Three shots! Three lives lost!”

After a series of bold moves, 16-year-old Elizabeth and her mother Roza took Catholic names, faked papers, forged connections, procured visas and made their way to the United States in 1946 to start life from scratch. “They kept these identities for the rest of their lives,” Alexandra says.

Ask the Bellaks if they have stuck to Christianity or returned to their Jewish roots, and Alexandra is quick to speak about her ‘secular’ upbringing. Her father, a Jewish man who survived persecution in Vienna, and her mother—both teachers at the Columbia University—tried to maintain a semblance of normalcy in their lives, she says. “They did not speak much of their past.” Elizabeth kept her Jewish identity hidden from her children till they were in their early teens. “My grandmother felt Catholicism saved them, so she wanted it to stay that way,” Alexandra says.

Renia’s diary is not just an account of the horrors of the Holocaust—it is also a peek into the teenager’s relation with her mother, sister Elizabeth who was then an aspiring actress, her stories of romance, the first kiss, and more. It is also a testament of how love survives through the darkest of times. Elizabeth remembers Zygmunt, who passed away in the 1990s, as the handsome, green-eyed, curly-haired boy her sister was smitten with. “He was able-bodied and heroic,” she says. “He loved her. He tried to save all of us.”

For the Bellaks, the book’s popularity has come as a huge surprise. What started as a humble project to trace one’s roots has now attained global significance. It is not an easy walk down memory lane as the octogenarian pieces together her childhood, revisiting the pain and the loss. “Renia, six years older than me, was like my surrogate mother,” says Elizabeth. “She took care of me, my clothes, books, everything.” But what defines Renia is her undying spirit. Says Elizabeth: “She was bright, reserved and thoughtful. She enjoyed life even under circumstances that were so difficult.”

Renia’s writings are bound to trigger comparisons with those of Anne Frank, one of the best known faces of the Holocaust. The Diary of Anne Frank, a compilation of the teenager’s memoirs of her family’s persecution during the German occupation of the Netherlands, is a classic of war literature. This is also why Renia has earned a new nickname—the ‘Polish Anne Frank’.