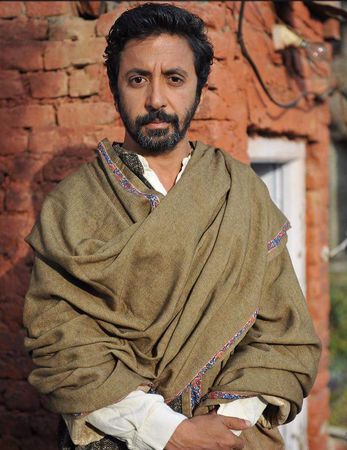

Oscar-nominated director Ashvin Kumar—who has explored terrorism in Kashmir in films like Inshallah Kashmir and Inshallah, Football—has just come out with his next film, No Fathers In Kashmir, after months of struggling for clearance from the central board of film certification. This time, he looks at militancy in the state through the love story of two 16-year-olds, both of whom have lost their fathers.

The film is deeply moving and, at some level, confusing, too, as it destroys many notions that non-Kashmiris have....

Welcome to my confusion. I have been confused for the last 10 years. First, to see what was going on, and then, to realise why it was not going out there. There is a direct relationship between censorship and creating fear, hostility and suspicion in the minds of people outside the state about what the people of Kashmir are going through. When you withhold information, you only allow people to make decisions based on the information that they have, and those decisions are not particularly enlightening because what you are telling them is [about] violence and hate. You show a stone-pelting kid, but you are not showing how that kid tried to go to school and his brother was shot dead. That is the reason he is throwing stones.

You started making Kashmir-based films in 2009. What keeps you so hooked to the state?

I went to the valley in 2009 and could not believe what was happening there, and how the media and government were all working hand-in-hand. The media is very independent. It has no problem covering the Naxal belt and [other] insurgencies in the country. I realised that Kashmir being an all-Muslim state, contiguous with China and Pakistan, makes it very different.

Was there any particular moment that drew you to the state?

The first time I held the hands of a girl was in Kashmir. My grandfather is from Kashmir, so my mother (fashion designer Ritu Kumar) is a half-Kashmiri. And I am a quarter-Kashmiri. We spent all our summer vacations in the state. My childhood was a time of innocence and tenderness. After 1989, we never went back because of the militancy. I went back in 2009 to make a movie, and [when] I saw the things that were happening, I decided to make a documentary. The initial draw was the stark difference I saw—a place I remembered as a paradise had turned dark because of the newspaper coverage. I was deeply intrigued by that.