When Puducherry-based playwright Koumarane Valavane heard the story of star-crossed lovers Shankar and Kausalya from Tirupur, he could not help seeing it through the lens of a Shakespearean tragedy. Shankar, a dalit, and Kausalya, an upper-caste Hindu, got married in 2015 amid severe family opposition. A year later, the couple was assaulted by an armed gang in broad daylight. While Shankar was hacked to death, Kausalya survived, albeit with grave injuries. She became an anti-caste crusader and fought the bail petition of her parents 58 times. While her father, the mastermind behind the murder, was sentenced to death in December 2017, her mother was acquitted. Kausalya continues to fight against her acquittal.

When Valavane met Kausalya, she told him how her mother once charged to the police station, shouting hate and revenge. “If you read the original Romeo and Juliet, when Tybalt (Juliet’s cousin) is killed by Romeo, it is Juliet’s mother who voices her burning desire to kill Romeo and seek revenge. Not her father,” says Valavane. If he had written the original, Valavane might have made the father spout the hate speech. But, Shakespeare did the right thing, he says. “He knew the soul of a woman... it is very strange. And see, this is how it still happens in real life, too,” he says, a day after the staging of Chandala, Impure at the 14th Mahindra Excellence in Theatre Awards & Festival on March 12. The play won the best supporting actor (male) and best lead actor (female) awards at META this year.

In Chandala, Valavane’s modern-day take on Romeo and Juliet through the prism of caste brutality, care is taken to retain this complexity of female psychology, even though there are several plot departures from the original. It is Janani’s raging mother who marches to her daughter’s hovel when she learns of Janani’s secret marriage with Jack, a dalit. The same Jack had also killed her notorious nephew.

Romeo and Juliet become Jack and Janani in Chandala, Impure. The action shifts from 15th century Verona to 21st century Villupuram in Tamil Nadu and the Capulets and Montagues are replaced by families in upper caste Vaishnava Nagar and the marginalised Ambedkar Colony. The basic framework of Romeo and Juliet—the passion and idealism of youthful romance, their rebellion against the strictures of family and society, the fateful forces that eventually overthrow the beautiful lovers—is so porous, it can be transferred to just about any context. Hence, one may sigh, ‘Please, not another adaptation of Romeo and Juliet’. But, Chandala is essential viewing, for the clever and highly inventive ways it transforms a cinematic text into a thrilling experience on stage for three hours on the trot. For not allowing room for a single surplus sequence. For creating memorable characters, especially Janani’s ayah (Juliet’s nurse), the bawdy link between the lovers. For the situational settings of a rambunctious small town where popular cinema is the only gateway drug for freedom and fantasy. “Is the famous balcony scene even possible in a middle class house in Villupuram?” asks Valavane. So, the lovers meet under the ayah’s skirt splayed out in a kathakali pose in the darkness of the night. “Do you expect the lovers to first bump into each other at a party in a stifling small-town society?” Valavane wonders. So, he makes them meet in an adult cinema hall, playing a film starring Shakeela. Ayah, Janani and her sister don a male disguise to watch their first soft-porn film in the company of a sweaty, heaving mass of men. It is here that Janani first feels Jack in the heat of the moment even before she lays her eyes on him. “This is a very complicated scene. And also my favourite,” says Valavane. “You, the audience, has a tantalising choice. What attracts you more? This adult movie scene or a real love story unfolding? It automatically makes the audience confront the complexity of sexuality, where the hero Jack doesn’t even know [whether] he is attracted to a man or a woman.” In Chandala, you will also find a flowery cupid capering around to the tunes of Yumeji’s theme from In the Mood for Love. And, the upright Janani is mute.

Valavane, who grew up in the port town of Karaikal, has always been in thrall to temple festivals and village performances. He left for France when he was 14. He has a French citizenship now, since his father served in the French military. Though he studied theoretical physics, his heart was always in theatre. He formed a travelling troupe in college, staging the Mahabharat, Antigone and The Barber of Seville across villages in France. That was his training ground, he says. “Here in India, we do not appreciate our folk theatre traditions or village performers.” In Chandala, he has interwoven powerful ritualistic performances and references as a comment on the vacuousness of the caste system: be it in the dance of Kali where a lower-caste individual is revered as a goddess for a day or the more sinister practice of deflowering a deceased upper-caste virgin, banned in the 1970s.

Valavane does not want his play to be seen as a tragedy, even though it does not have a happy ending. In the original, the lovers are sacrificed, followed by reconciliation between two warring families. In Chandala, the death of the lovers will not demolish the caste system. “But the change is already happening,” he says. “It is in the energy of the youth, the actors who will transform the society. Love is the silent revolution.” He says the audience will enter a state of ‘ananda’ [from Natyashastra] with this play even when there is death. “‘Ananda’ is when you believe in something,” he says, “when you feel connected with others, with the cosmos, some shakti, some strange energy.”

Reimagining Shakespeare in India

In Sonnets c.2019, director Anirudh Nair rejigs the bard’s lovestruck sonnets into a play that is performed in his duplex apartment in Delhi. In this site-specific piece, the audience moves from one part of the house to another with the writer, the muse and the lover, intimately watching the “ever-fixed mark” that is love being constantly shaken in the tempests of the 21st century.

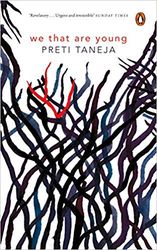

In British-Indian writer Preti Taneja’s debut book We That Are Young, Shakespeare’s King Lear is reset in Delhi’s rich and dirty universe of a business conglomerate, which has at its centre the ageing patriarch Devraj and his daughters Gargi, Radha and Sita. The book, which won the Desmond Elliott prize in 2018, will now be made into a TV series, reportedly co-produced by Narcos’s Gaumont studio.

The National Centre for the Performing Arts in Mumbai presented Lucrece last November. Based on Shakespeare’s narrative poem, The Rape of Lucrece, the play stars Kalki Koechlin as the central character who is raped and who narrates her experience with dignity and honesty. Directed by Paul Goodwin, the 265 stanzas of the poem are deftly whittled down to an hour-long performance.