It was the Arabs who charted the world’s most ingenious sea route.

Half a millenium ago, they discovered that if they set sail from a North African port in late April, the wind would take them to a hilly cape in Kerala’s Kannur district in about 40 days. They could then turn south, and sail along the coast till they reached the prosperous port of Calicut, in the kingdom of the mighty Zamorin, where they could trade in spices, scents and slaves. The sailors would make landfall with the seasonal rain and leave with it, too. The retreating monsoon would take them back home, much the same way they had come.

In the 15th century, the Portuguese got wind of this magical passage. King Manuel I dispatched his trusted sailors to open a trade route for him to Calicut. Four ships and 170 men skippered by Vasco da Gama thus reached Malindi, a Moor kingdom now part of modern Kenya. They wined and dined there for nine days, and set sail for India with the help of a Gujarati trader and an Arab guide who knew the course.

The rest is painful history.

Centuries on, that history finds reverberations in the fourth and latest edition of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, South Asia’s most popular art jamboree that began on December 12 last year and ends on March 29. Occupying pride of place at Aspinwall House, the biennale’s primary venue, is Messages from the Atlantic Passage, an awe-inspiring exhibit by South African artist Sue Williamson. Five fishing nets filled with grimy bottles hang from the high ceiling of a hall, water dripping from them to rectangular pools built on the wood-panelled floor. The deck and the pools signify the ships that carried millions of slaves across the Atlantic, to work in cotton plantations in America and sugarcane fields in the Caribbean. The bottles—around 2,000 of them—contain colonial records of individuals who were forced to live and work in lands alien to them.

Messages from the Atlantic Passage is a striking representation of the global consequences of Gama’s voyage to Calicut, which threw open the east to the plundering west. It is strangely poetic that Williamson hails from Cape Town, which is near the great promontory that the Portuguese named the Cape of Good Hope in celebration of the opening of the sea route to India. But where the Portuguese saw hope, Williamson discovered misery.

“I came to Kochi as a visitor last year, and I was completely struck by our similar history,” she told THE WEEK. “In Cape Town, we have the accurate transaction records of the enslavement of Indians, who were brought to South Africa by the Dutch East India Company in the 17th century.”

Williamson’s exhibit fits in well with the theme of this biennale—‘possibilities of a non-alienated life’. It is a phrase that sounds like one of those highfaluting art-world jargons, but is just an awkward translation of a rather untranslatable Malayalam catchline, Anyathayilninnu ananyathayilekku. (A running joke in the last edition of the biennale was its theme: Forming in the pupil of an eye. “Like a cataract?” people scoffed then. That phrase, too, was a jarring translation of a tongue-twisting Malayalam beauty—Ulkazhchakaluruvaakunnidam, roughly translated as a womb for insights.)

Untitled (TWO Minutes To Midnight) by Jitish Kallat (India). A sculptural installation modelled on the Doomsday Clock, which represents how close the world is to a manmade global catastrophe. A metaphor for the human plunder of earth, it shows artefacts from the prehistoric past (placed on the minute hand) nearing the midnight hour (doomsday) | Vipin Das P.

Untitled (TWO Minutes To Midnight) by Jitish Kallat (India). A sculptural installation modelled on the Doomsday Clock, which represents how close the world is to a manmade global catastrophe. A metaphor for the human plunder of earth, it shows artefacts from the prehistoric past (placed on the minute hand) nearing the midnight hour (doomsday) | Vipin Das P.

‘Possibilities of a non-alienated life’, however, is splendidly attuned to the ethos of the biennale’s host towns—Fort Kochi and Mattanchery. The narrow lanes belie the breadth of the cultures coexisting here—Sindhis and Gujaratis, Marathas and Dawoodi Bohras, Anglo-Indians and Malabar Jews, to name a few. All descendants of aliens who long discovered possibilities of a non-alienated life here.

Equally cosmopolitan are the exhibits and paintings displayed at Aspinwall House, a heritage building that is the biennale’s primary venue. Aspinwall has been divided into several ‘fragments’, each fragment housing a dozen works that are diverse yet interconnected.

There is Lebanese filmmaker Rania Stephan’s The Three Disappearances of Soad Hosny, which gives a fascinating timeline of the rise and fall of Egyptian cinema through the eyes of its most famous star, Hosny aka the Egyptian Cinderella; Neelima Sheikh’s Salaam Chechi, an illustrated ode to the globe-trotting Malayali nurses, “the unsung heroes of the medical field”; The Clothesline by Mexican artist Monica Mayer, which chronicles the social experiences of women “using an element that alludes to a traditional female activity”; Samsung Means to Come, a delightful text-and-music short about a woman who imagines having sex with a Samsung dishwasher, by Seoul-based collective Young-Hae Chang Heavy Industries; and Kenyan artist Cyrus Kabiru’s C-Stunners, an identity-defying series of self-portraits.

The collection is eclectic and engrossing.

Most of the works, though, are not optimistic expressions about exploring life’s possibilities. Instead, they give a sense of regret, dismay and belligerence. Delhi-based artist Aryakrishnan’s Sweet Maria Monument is a wistful tribute to Anil Sadanandan aka Sweet Maria, a pioneering Malayali transgender activist who was brutally murdered in 2012. She was stabbed in the stomach and her neck was slit, after canards spread that she was an AIDS patient who was on a campaign to infect others.

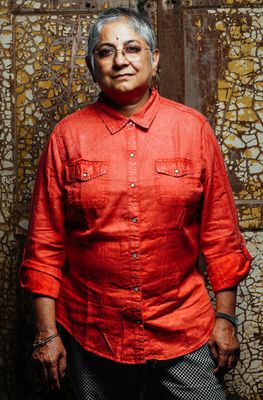

Srinagar Biennale curated by Veer Munshi (India). One of four infra-projects of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, exhibiting works that explore the identity crisis of Kashmiris who live through conflict, migration and displacement. (In pic) Munshi at A Place for Repose, which houses “symbols of resistance and resilience” | Sanjoy Ghosh

Srinagar Biennale curated by Veer Munshi (India). One of four infra-projects of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale, exhibiting works that explore the identity crisis of Kashmiris who live through conflict, migration and displacement. (In pic) Munshi at A Place for Repose, which houses “symbols of resistance and resilience” | Sanjoy Ghosh

Aryakrishnan labels the monument as an “ephemeral archive” of Maria’s personal space. It has her bed, dressing table, cosmetic articles, collection of books—Jean Cocteau’s The White Paper nestles against the Kama Sutra—and sundry other possessions spread across the room. All of it is dominated by a 16-foot red skirt, which was born out of a strange dream Aryakrishnan had, in which Maria asked him to put a bed under her skirt, “one that was big enough to feed 5,000 people”.

“The skirt connects to Maria and her kind of aesthetics,” she says. “It also resembles monuments of Left political parties. But, it is not solid like a traditional monument. It is floating, because trans lives are not stationary.”

The melancholy of Sweet Maria Monument contrasts starkly with the angry activism of The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist, by the New York-based feminist group Guerrilla Girls. Their series of campaign-style posters asks pointed questions: Such as, how many women had one-person exhibitions at NYC museums last year (1985)? The answer: Guggenheim—0; Metropolitan—0; Modern—0; Whitney—0.

Another poster asks the same question for the year 2015. The answer: Guggenheim—1; Metropolitan—1; Modern—2; Whitney—1. And then you get the acid humour of The Advantages of Being a Woman Artist.

The Guerrilla Girls was the toast of the biennale town in the opening weeks of the event. At the biennale’s signature show Let’s Talk, they declared that art needs to become a form of activism to bring about social change. One visitor who was bowled over by their zeal was Andre Wang, who is part of the Singapore Biennale. “This [the activism] just would not happen in Singapore,” Wang told THE WEEK. “Things are heavily controlled [in Singapore], and the artworks are less political. If you go through the galleries, you will see all these feminist ideas and bold statements, [but only] in a subverted way, or in a way that the meaning is hidden.”

The spirit of radical chic that engulfs this biennale owes a lot to its curator, Anita Dube. The 60-year-old artist and art historian was one of the founding members of the short-lived, but influential ‘radical art movement’, launched in the 1980s by a group of mostly Malayali artists. (The Lucknow-born Dube was an exception.)

She wrote the group’s ‘radical manifesto’, which denounced the traditionalists, labelling them as “narrative painters” who were disengaged from social issues. “The radical movement fundamentally changed the art scene in India,” said Bara Bhaskaran, THE WEEK’s illustrator whose works were part of the previous biennale. “It broke the romantic, ivory-tower concepts about what constituted art and helped the rise of a new generation of artists who successfully experimented with a diverse range of forms and styles.”

The rad artists also protested the commodification of the Indian art scene, once even staging a demonstration against a Sotheby’s auction in Mumbai that had the backing of a prominent media house. “The [media house’s] sudden interest in Indian art and culture now shows that the imperialists want to completely poison the people’s mind and life through antihuman projects for artists,” read a pamphlet distributed by Dube and colleagues.

Dube has come a long way since, and her critically-acclaimed works have been displayed at prominent galleries and museums in India and abroad—the Gallery Nature Morte in Delhi, the Mattress Factory in Pittsburgh, the Walker Art Centre in Minneapolis, to name a few. Weeks before the opening of the Kochi-Muziris Biennale curated by her, she was interviewed by Sotheby’s. Asked whether the biennale would be “very political”, she replied, “The biennale is not going to be political in a sloganeering sense; sometimes these positions can be too determinate, counterproductive and polarising.”

For the biennale, Dube chose 93 works of 135 artists from 31 countries. All selected works are as reflective as they are political, showing that her dream of transforming the world through art endures. “When you are young, there are some key things,” Dube told THE WEEK. “And however much you change, those things remain.”

One thing that has remained is her aspiration to make things inclusive. “We have to get the voices that are at the edges into the discourse,” she said. “We must look at not just the glamour world of art, the star system. Look beyond that star system, and we will be able to find exquisite things happening.”

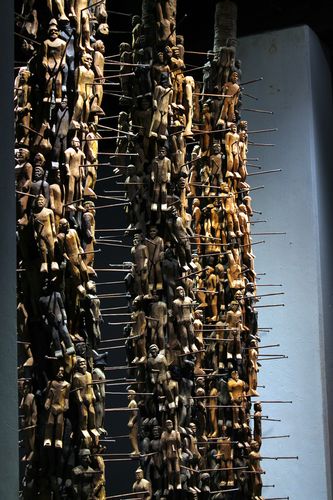

V.V. Vinu’s Ocha (Noise) is one such exquisite thing. It is an exhibit that has several life-size wood sculptures and more than 300 wood figurines nailed to three coconut-tree stumps that are 12 feet high. The figurines show human beings, all outcasts, in various poses—standing, sitting, eating, toiling and making love. The sculptures are made of timber from the tree that bears the poisonous odallanga, once the favourite of village women who wanted to end their lives. In the old days, the timber was also used to fence in property.

Ocha is an allegory of how communities, such as the dalits, are alienated in their own land. And it strangely contrasts with Williamson’s Messages from the Atlantic Passage, for Ocha tells you that you need not journey great distances to become alienated. “I was born in 1974. I felt alienated from the mainstream right from my childhood. You begin to think that this alienation happens because there is something wrong in you, but then you realise that it is the systems that are wrong, not you,” said Vinu. The Kochi-based artist’s exhibit called Noon Rest was selected as a signature piece of last year’s Shanghai Biennale.

Dutch artist Juul Kraijer’s photographic self-portraits—which disturbingly fuses her body to animals and plants—symbolise the alienation from within. “For me, as a spectator, they are about transcending the boundaries of the self and merging with what lies beyond,” said Kraijer. “It is conveyed not by symbolic motives, but rather by archetypical ones, like the human body fusing with a tree or snakes, like entrails or arteries writhing in the body.”

Questions of identity have also put gender issues in focus. Dube is one of the select few women in the world who have curated art projects of this magnitude. And she has made history by curating a biennale in which more than half the artists are women. “This is the first biennale in the world to have more than 50 per cent women artists,” said Dube. “For me, this is about the concerns that women have. If we just go in one direction of ‘manliness’, we are doomed. There would be more violence, more aggression. So, what we are bringing here is the quality that women can contribute to this world.”

Connoisseurs who have been keenly following the Kochi-Muziris Biennale since its inception in 2012 appreciate what Dube has done with this edition. “The biennale has become matured in terms of its confidence,” Sally Tallant, director of Liverpool Biennial, told THE WEEK. “It is doing an amazing job working locally and globally at the same time. One important reason I come here is that I get to see artists from India; artists from South Asia; artists I have not met before, whom I can present at Liverpool.”

Italian art historian and curator Fabio Cavallucci was struck by how Dube touched political and social issues in a straightforward way. “I have to appreciate that,” he said. “It is not normal in exhibitions to speak always in such a direct line.”

When it opened in December, the biennale was greeted with mixed reviews. A refrain of critics was that Dube’s curation had made the biennale brash and loud, that there were more in-your-face exhibits than paintings that require sober contemplation.

But, as weeks passed, the raps gave way to raves. “Had the biennale been a two-week event, it would have failed,” said artist and critic Upendranath T.R., whose works were part of the first biennale. “The main strength of the biennale is that it is open for three months, giving people the opportunity to go for repeated viewings, delve deep into each work, appreciate its textures and grasp its meanings.”

The biennale has a team of 20 art intermediaries, who take visitors on guided tours through all its 10 venues. The intermediaries have been chosen from varied fields—there are art students, architects, musicians and journalists. “They are doing an amazing job,” said Upendranath. “They beautifully explain each work, its artistry, and the significance of its placement. I found that my first impressions were deceptive. It is only after you shed your prejudices, open the windows of your mind and try and transcend your limitations that you can truly appreciate the significance of what is on display.”

What is not on display, but palpable nevertheless, is the sliver of scandal surrounding this biennale. In October, Riyas Komu, artist and cofounder of the Kochi Biennale Foundation, had to step down from his managerial duties after allegations of sexual harassment were levelled against him by an anonymous person.

“Though the foundation has received no formal complaint, we are collectively committed to ensuring zero tolerance to any harassment or misconduct, and have decided to constitute a committee to inquire into this matter,” said a press release from the foundation after the #MeToo scandal broke.

Komu, along with KBF cofounder and president Bose Krishnamachari, had played an instrumental role in conceiving and organising the biennale. His forced absence from the biennale milieu has been conspicuous, more so because he runs URU, an art hub that is close to one of the biennale venues.

Two months after the allegations against Komu surfaced, #MeToo struck again. Caught in the crosshairs this time was a prominent Indian artist whose work was to feature in a high-profile, biennale-related auction. The work was quietly withdrawn. There are now whispers of another #MeToo revelation hanging like the sword of Damocles over the biennale, but none has so far surfaced.

“All women are strong supporters of #MeToo,” said Dube. “So, we are putting pressure on the organisation to strengthen the structures within, so that women [do not find themselves] to be in positions where they feel disempowered. So, it is one thing to take action, which is Riyas stepping down; the second important thing is how you strengthen the organisation from within and make it accountable.”

The touch of scandal has brought a surreal quality to this biennale. It is like watching Pleasantville, the Garry Ross film in which two modern-day teenagers are transported into the world of a 1950s, black-and-white sitcom called ‘Pleasantville’, where everything happens according to script. With their unscripted actions, though, the rebellious teens begin to ‘ruin’ the classically picture-perfect landscape of the sitcom—leaves turn from grey to green, roses begin to bloom in red, and paintings come to vivid life, bringing life and colour to the black-and-white world.

The Kochi-Muziris Biennale, too, seems to be experiencing something similar—art getting a reality check, bringing colour and confusion. Perhaps, it bodes well for the biennale that it is no longer the arty Pleasantville it once was.