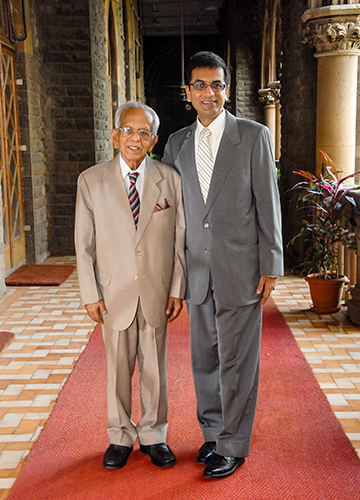

FORMER CHIEF JUSTICE of India (CJI) P. Sathasivam was known for his frank opinions and active presence on Facebook―an unusual trait among judges. Two days before he demitted office on April 26, 2014, he emphasised the importance of discipline and punctuality, saying the values should be ingrained in judges at all levels. A strong proponent of judicial reforms, he was also a vocal advocate for fixed tenures for CJIs.

“I had a tenure of nine months and eight days as CJI. There were many things I wanted to do but couldn’t because of the short tenure. The CJI must have a fixed term like some important government functionaries, such as the Union home secretary,” he said in his farewell speech.

Justice Sathasivam, 75, served as the 40th CJI from July 19, 2013, to April 26, 2014. With a career spanning over 18 years, his call for a fixed CJI term reflected the challenges posed by short tenures, which often result in a revolving-door approach to the nation’s highest judicial office.

More than a decade later, his words find resonance as Justice Sanjiv Khanna’s six-month tenure as CJI ends on May 13―making it one of the shortest in recent history. Appointed on November 11, 2024, Khanna, the serving CJI, will have a brief term, dictated by the mandatory retirement age of 65, illustrating the limitation Sathasivam highlighted.

A CJI’s tenure is dictated by their age and date of elevation to the Supreme Court. As per convention, the senior-most judge is appointed as the CJI. While Supreme Court judges retire at 65, the date of a judge’s appointment to the top court plays a crucial role in determining their tenure as CJI rather than just their age.

This ensures a line-up of future CJIs, with only unforeseen events like death, early retirement or impeachment potentially altering the sequence. In case of two judges being elevated to the Supreme Court on the same date, the one who takes oath first is given priority, followed by the judge who has put in more years of service in the high courts.

The debate over fixed tenures for CJIs is gaining further attention after Justice Joymalya Bagchi’s appointment to the Supreme Court on March 17. Justice Bagchi is projected to become CJI on May 26, 2031, following Justice K.V. Viswanathan’s retirement. However, his term as CJI will last just over four months, making it one of the shortest anticipated tenures in the Supreme Court’s succession line.

The rapid turnover of CJIs is accelerating. Nine CJIs are slated to assume office over the next eight years, with three different CJIs serving in 2025 alone. This constant leadership changes raise concerns about continuity, stability and the ability to implement long-term judicial reforms. While some CJIs have made significant contributions despite short tenures, experts argue that frequent leadership changes make it difficult to pursue sustained institutional improvements. Judicial reforms require careful planning, consistent policy direction, and time to take effect. But, with CJIs serving only a few months in some cases, crucial administrative and legal overhauls risk being left unfinished or abandoned altogether.

A limited tenure also means CJIs may not have enough time to fully grasp the Supreme Court’s internal dynamics. While judges elevated directly from the Supreme Court Bar, like Justice U.U. Lalit, bring decades of experience in the Supreme Court’s functioning, those who have spent most of their careers in high courts may need time to adjust. Unfortunately, by the time they do, their retirement is already approaching.

For instance, former CJI D.Y. Chandrachud, with a tenure of over two years, led 23 Constitution benches, authored 612 judgments, and spearheaded significant technological advancements like hybrid hearings. But as his retirement date drew close, he chose not to hear a batch of petitions on marital rape, saying that the next CJI should decide. Justice Khanna, his successor, has yet to assign the case to a bench.

Similarly, Justice Khanna, while granting bail to former Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal in 2024, referred a larger issue concerning the Enforcement Directorate’s powers under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act to a special bench. The bench is yet to be constituted.

Legal experts say brief CJI tenures often lead to deferred decisions on important cases. Judges with short tenures may avoid handling long-pending Constitution bench cases. This, say experts, will not only hamper the efforts to reduce the backlog of five crore cases, but also reduce the chances of CJIs implementing policy reforms.

Moreover, the CJI plays a crucial role in forming the collegium along with four senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, which decides judicial appointments. “The CJI should have a minimum tenure of three years to ensure that long-standing reforms can be implemented,” said former attorney general K.K. Venugopal.

But even short tenures can yield positive outcomes. “The current CJI has a short tenure of six months, but he has made two outstanding judicial appointments to Supreme Court,” said senior advocate Sanjoy Ghose.

Unlike other constitutional posts, the post of CJI continues to lack a fixed tenure despite the Law Commission of India recommending a minimum tenure of two years. In 1958, the 14th Law Commission Report said continuity was essential in the office of the CJI to maintain quality in judicial administration. It also suggested that the CJI spend time touring the country to meet judicial personnel and members of the bar to understand issues.

The longest tenure of seven years and four months (1978-1985) as CJI has been that of Y.V. Chandrachud, D.Y. Chandrachud’s father. The shortest tenure of CJI has been that of K.N. Singh―17 days. Justice B.V. Nagarathna, who could become the second female CJI in September 2027, would serve only for 36 days.

The Constitution is silent on the CJI’s tenure. Article 124, which deals with the establishment and constitution of the Supreme Court, says: “Every judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President by warrant under his hand and seal and shall hold office until he attains the age of 65 years.” There is no mention of the duration of the tenure.

Ashwani Dubey, advocate-on-record in the Supreme Court, said a CJI with limited time in office struggles to implement systemic changes. “This also weakens institutional stability as every new CJI must reset priorities instead of building on long-term reforms, which are key in tackling judicial backlog and ensuring procedural efficiency and consistency in constitutional interpretation.”

Most Supreme Court judges are appointed in their late fifties. As a result, those who are among the handful who ascend to the CJI’s chair usually do so when they have limited time before retirement. Also, with appointments made solely based on the seniority-focused collegium system, CJI tenures end up varying drastically.

Indian judges have shorter tenures than their counterparts around the world. Judges retire at 75 in the UK and 70 in Canada. In Australia, Belgium and Norway, judges work till 70, while those in the US, Russia, New Zealand and Iceland never retire.

The absence of a fixed tenure for CJIs continues to pose challenges. Experts say a fixed term would ensure that each CJI has enough time to implement meaningful judicial and administrative reforms. With the rapid turnover of CJIs set to accelerate in coming years, the question remains―how long should the CJI serve to make a lasting impact?