It all started with a telephone call received by the Delhi Fire Service on March 14 around 11:30pm that a fire had been spotted in a storehouse near the official residence of Justice Yashwant Varma of the Delhi High Court. Firefighters, upon extinguishing the blaze, discovered sacks of partially burned cash. As Justice Varma was out of town, his private secretary alerted the police. The matter soon snowballed into a major controversy as Delhi Police Commissioner Sanjay Arora informed the chief justice of the Delhi High Court about the discovery of the burnt notes. Following protocol, the chief justice alerted Chief Justice of India Sanjiv Khanna and submitted an inspection report.

Justice Varma, upon returning to Delhi the next day, said he had nothing to do with the money. He said the room was used to store discarded household items and was accessible to staff and other workers. On March 20, a preliminary report was submitted to the CJI, prompting the formation of a three-member inquiry committee. Subsequently, the Supreme Court collegium recommended Justice Varma’s transfer to the Allahabad High Court.

The incident has opened a Pandora’s box―there are reverberations in Parliament, with lawmakers questioning the process of judicial appointments, legal experts raising concerns about the effectiveness of checks and balances within the judicial system, and the common man wondering whether judiciary can still be trusted.

This is not the first time the judiciary has come under scrutiny. Similar cases have been reported in the past when judges faced serious allegations. A notable case involved Justice Soumitra Sen of the Calcutta High Court, who became the first Indian judge to be impeached by the Rajya Sabha in 2011 for misappropriation of funds. Sen was accused of diverting Rs33 lakh while serving as a court-appointed receiver in a legal dispute, retaining the funds for personal use even after his elevation to the judiciary.

Another instance is the 2009 ‘cash-at-judge’s-door’ scandal involving Justice Nirmal Yadav of the Punjab and Haryana High Court, when a bag containing Rs15 lakh was allegedly delivered to her residence, intended as a bribe. In 2012, a ‘cash-for-bail’ scam came to light when CBI Special Judge Talluri Pattabhirama Rao was arrested for accepting Rs5 crore as bribe for granting bail to mining baron Gali Janardhan Reddy in an illegal mining case. However, no judge has been impeached in the country since independence. This has reignited the debate on the lack of options available to deal with judicial corruption.

Supreme Court Advocate-on-Record Ashwani Dubey said the lack of prosecutions in corruption cases involving judges underlined the argument that the current mechanisms were inadequate to address judicial corruption. He has called for urgent reforms that could pave the way for revising Supreme Court judgments that protect judges from strict scrutiny. Dubey also questioned the delay in implementing the Supreme Court’s observation on the need for judges to declare their assets. According to official data, there are around 1,100 judges in the high courts and 33 in the Supreme Court, but only 98 high court judges have made details about their assets publicly available.

Although no judge has ever been impeached or convicted for corruption in India, there are two routes through which action can be taken against Supreme Court and high court judges. The first is an in-house inquiry by the Supreme Court to deal with complaints against judges, which may result in the judge resigning or not being allocated judicial work. In rare cases, sanction for prosecution is sought from the competent authority. The second route is impeachment by Parliament, which, if passed by both Lok Sabha and Rajya Sabha, can result in the termination of the judge’s tenure. In 2003, the Supreme Court ruled that in-house inquiry reports are confidential. As a result, the number of judges facing inquiry, and the action taken, remain unclear.

Every year, the Union ministry of law and justice receives questions in Parliament on the number of corruption cases pending against judges, but after each time the minister shares the figure, what further action has been taken remains a mystery. Last year, the ministry informed Parliament that over 1,700 complaints were received and forwarded to the CJI for action. Recently, the Supreme Court collegium is learnt to have initiated an in-house procedure against Justice Shekhar Yadav of the Allahabad High Court for alleged communal remarks made at a Vishva Hindu Parishad event on December 8. While the outcome of the inquiry remains unclear, Justice Yadav continues to remain in service.

Dubey said the lack of impeachments pointed to the need to rethink the options available to deal with judicial corruption. Another reason attributed to the low conviction rate is the absence of action in corruption cases due to the non-granting of sanction for prosecution against judges. For instance, the Supreme Court has been hearing a case to decide whether the Lokpal has the power to investigate judges in corruption cases. The apex court stayed a Lokpal order against an unnamed high court judge over a corruption complaint.

Experts argue that while mechanisms such as judicial oversight and impeachment exist to keep errant judges in check, there remains the unspoken issue of political influence affecting the transparency expected from the judiciary. The judiciary’s insulation―intended to uphold its independence―can, at times, shield misconduct, leading to a lack of transparency, they say. This underscores the urgent need for stronger accountability and stricter ethical oversight. Beyond individual cases, a deeper examination is essential to assess the extent of the problem and to explore effective solutions.

Strict accountability measures, transparent judicial appointments and financial independence of the judiciary are essential to combat judicial corruption. The independence of the judiciary must be preserved, but not at the cost of shielding wrongdoing. Accountability mechanisms such as accessible complaint systems or random case audits to deter corruption are immediate steps towards ensuring transparency.

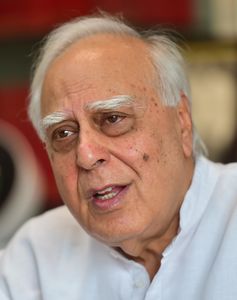

“Judicial corruption is a grave concern,” said Senior Advocate Kapil Sibal. “Corruption is a serious issue not just within the judiciary but across society. Despite several assurances, corruption has only increased.” Sibal pointed to the lack of transparency in judicial appointments, inadequate accountability mechanisms and the judiciary’s resistance to external oversight as factors aggravating the issue. “The Supreme Court has been too soft in dealing with errant judges,” he said.

A closer look at in-house mechanisms reveals that the process is largely opaque. It also becomes ineffective, as no FIR can be registered against a judge without the CJI’s approval. This means that while checks and balances exist within the judicial system, systemic inefficiencies and weak enforcement of ethical standards are at the root of the problem. Another facet of corruption within the judiciary stems from delays and pendency hurting the system―five crore cases are pending across the country. The solution to tackling pendency lies in appointing judges up to the sanctioned strength.

Calling for an FIR in the Justice Varma incident, Justice S.N. Dhingra, who served at the Delhi High Court, said there was deep-rooted corruption within the judiciary. “I don’t understand why the Supreme Court has not allowed the filing of an FIR till now. A judge is not above law.”

Emphasising the need for a relook at the collegium system, former attorney general Mukul Rohatgi said there was a pressing need to review how judges were appointed and disciplined. Criticising the collegium system as unsatisfactory and opaque, Rohatgi said the Supreme Court had interpreted the Constitution selectively. He referred to past efforts to bring about transparency, such as the National Judicial Appointments Commission (NJAC), which was struck down by the top court. Rohatgi said a middle path was the way forward―introducing external oversight through an independent committee to recommend judicial appointments, rather than the current system of judges selecting judges.

One example of an allegedly flawed appointment under the collegium system was that of Soumitra Sen. His elevation occurred despite allegations of misappropriating funds while serving as a court-appointed lawyer in a dispute between two public sector undertakings. The collegium cleared his appointment and allegedly withheld knowledge about his background before elevating him to the bench.

Justice J. Chelameswar, the sole dissenting judge in the NJAC case before the Supreme Court, raised serious concerns about the functioning of the collegium. In his dissenting note, he wrote: “We, the members of the judiciary, exult and frolic in our emancipation from the other two organs of the state. But have we developed an alternate constitutional morality to emancipate us from the theory of checks and balances, robust enough to keep us in control from abusing such independence? Have we acquired independence greater than our intelligence, maturity and nature can digest? Have we really outgrown the malady of dependence or merely transferred it from the political to the judicial hierarchy?.... Proceedings of the collegium are absolutely opaque and inaccessible, both to the public and to history, barring occasional leaks.”

Legal experts believe that unless a formal system is introduced to regularly evaluate judges and their performance in the lower courts, the collegium’s appointments will continue to be a hit-or-miss exercise, with some doubtful appointees slipping through the cracks. “It is time for the Supreme Court to re-evaluate how judges are appointed. The process must be more transparent and carefully executed,” said Sibal.

What makes the matter difficult to resolve immediately, either by the legislature or the judiciary, is the constitutional framework designed to ensure judicial independence from executive influence. These provisions are vital for judges to deliver impartial verdicts, free from inducements.

The Constitution also sets out procedures to address judicial misconduct. A judge may only be removed via a motion in Parliament passed with a two-thirds majority in both Houses. Justice V. Ramaswamy of the Supreme Court was subject to such a motion in 1993. The preliminary inquiry committee found the charges valid, but the motion failed to garner the necessary support in the Lok Sabha. Justice Sen, meanwhile, resigned after the Rajya Sabha passed the impeachment motion against him.

Meanwhile, as controversy continues over the source of the recovered cash and whether Justice Varma is being unfairly targeted, Rohatgi has supported a forensic investigation. The forensic team is expected to scrutinise phone records of employees at Justice Varma’s residence and review statements from the fire department. Justice Varma, who has been placed on leave pending investigation, has been instructed not to delete his call history.

Justice Varma was transferred from the Allahabad High Court to the Delhi High Court in 2021. The Supreme Court has now recommended his return to his parent high court, a move that has attracted criticism. The top court’s assertion that the transfer is unrelated to the alleged cash recovery has been met with scepticism. “I never understood this statement [of the Supreme Court] that this transfer has nothing to do with the cash scam. In my view, it is because of the cash scam that he is proposed to be transferred,” said Rohatgi. “We need to get to the root of the matter―whether the judge is guilty of misconduct or moral turpitude, or if his reputation is being unfairly maligned.”

The Allahabad High Court Bar Association has launched an indefinite strike against the proposed transfer of Justice Varma. Association president Anil Tiwari said the protest was not against any court or judge but against those who betrayed the judicial system. “For now, our demand is a reconsideration and withdrawal of the transfer order.”

Lawyers have expressed broader concerns about the implications of such transfers. They argue that public trust is eroded when a judge facing an internal inquiry is allowed to preside over cases. Litigants, they contend, would be reluctant to have their matters heard by a judge under suspicion. Until a judge is cleared of allegations, experts suggest, any transfer should be put on hold in public interest.

But the elephant in the room remains: despite past and present cases highlighting the need for robust checks and balances, incidents like these continue to emerge. Take, for instance, the case of Justice Nirmaljit Kaur of the Punjab and Haryana High Court. On August 13, 2008, a bag containing Rs15 lakh was mistakenly delivered to her. The intended recipient was another judge, Nirmal Yadav. The Supreme Court collegium, headed by CJI K.G. Balakrishnan, cleared her name. Justice Yadav, meanwhile, was transferred to the Uttarakhand High Court. On the day of her retirement in 2011, the president approved her prosecution. Fourteen years later, the case remains pending before a CBI court, underscoring the systemic delays and unanswered questions surrounding judicial accountability.

At present, there is no fixed timeline for the in-house committee, constituted by the Supreme Court, to conclude its investigation into the alleged cash recovery at Justice Varma’s residence. If the committee finds the allegations credible, the CJI may recommend that the judge resign or opt for voluntary retirement. If the judge refuses, the CJI will inform the president and the prime minister of the findings, potentially triggering formal impeachment proceedings.

Ensuring that justice is not only done but is seen to be done is paramount. Until in-house committee reports are made public, the opaqueness of the system will continue to raise concerns. Whether there exists a conflict of interest, given the judiciary’s self-regulation without an independent oversight body, remains a grey area. Open discussions or investigations into allegations of judicial corruption are constrained by strict laws regarding contempt of court, which, in turn, stifle public scrutiny. Does this make current deterrents ineffective? As ever, the jury is out.