EVER SINCE MILITANCY forced Kashmiri Pandits to leave the state in the late 1980s, they have found themselves at the centre of debates in places big and small, from tea stalls to newsrooms to Parliament.

The latest debate stemmed from the film The Kashmir Files, which its makers and some politicians, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, described as the correct portrayal of atrocities the militants committed against Kashmiri Pandits. Social media burned for weeks with users lobbing allegations from both sides. There were calls to rehabilitate the Kashmiri Pandits and punish those who hurt them.

While the film’s success and the impending elections in Jammu and Kashmir could speed up the Pandits’ return to Kashmir, several of them have already, quietly, been making their way back. Satish Mahaldar, for one, believes it is time to shun the bitterness and move on. He heads the Jammu and Kashmir Peace Forum (JKPF), which works for the rehabilitation of Kashmiri Pandits. The organisation wants the Centre and the Jammu and Kashmir government to take steps for the return of the Pandits without delay. Mahaldar has been visiting Kashmir regularly and claims that even separatists are on board with his plans. In 2019, separatist leader Mirwaiz Umar Farooq told a JKPF delegation that Kashmiri Muslims were incomplete without Kashmiri Pandits, and that the Hurriyat would do everything for their safe return.

Mahaldar told THE WEEK that the JKPF had gathered support from a variety of Kashmiris, but the administration was not cooperating. A few years back, he said, 106 Kashmiri Pandit families were ready to return with the JKPF’s help. “The plan was to buy land and start the project with the help of the Jammu and Kashmir Housing Board under the build, operate and transfer model, but they refused,” he said. The revocation of Article 370 and the Covid-19 pandemic did not help.

About two years on, the JKPF has now resumed work. On April 2, it organised an event to celebrate Navreh (Kashmiri Pandits’ new year) in Srinagar’s Sher-e-Kashmir Park. The festival saw many migrant Kashmiri Pandits returning and mingling with the locals. “I am happy to be here,” said Monica Koul, who came from Delhi with her daughter, a Class 9 student. “My childhood friend Sumaira Zahoor is also coming here. She lives near Dargah Hazratbal.” Koul also re-established contact with childhood friends and the teachers who taught her at Vishwa Bharti, a school in Srinagar.

The last time Koul was in Kashmir, she met the neighbours who had bought her childhood house at Ali Kadal in Srinagar after her family left Kashmir. The neighbour’s house had burnt down. “They came looking for us in Saharanpur in Uttar Pradesh and requested my father to sell the house,’’ she said. “My father agreed as we needed the money. Until he died in 2019 of Parkinson’s, he kept a pair of keys to the house with him.

“[The neighbours] received me with open arms and said you are always welcome. I told them if they decide to sell the house, I would like to buy it. After all, roots are roots. When my son was with me here for a week, he told me, ‘Now I realise why you crave for Kashmir’.”

Anjali Ada, a social activist who came from Delhi to attend the festival, once had a house at Barbuj Kocha in Habba Kadal in Srinagar. “I come to Kashmir every year,” she said. “I have also brought my team from Delhi. We get a lot of love from the people here.”

She said Kashmiri Pandits were waiting for the government to help them return. Some others, however, have been more enterprising. Sandeep Wali, who works in an insurance company, visits Kashmir regularly and has made many friends. He was six when militancy forced his family to flee from Nuner, a village in Ganderbal in north Kashmir, to Jammu in the south. “My father was in his late thirties when we left,’’ he said. “Despite working as a chief accounts officer in the government, he had to invest 15 years and his savings to build a house in Jammu.”

Is security not an issue anymore for those wanting to return? Last year, several Kashmiri Pandits, including noted chemist M.L. Bindroo, were killed by militants. “His killing was tragic, but our feelings about Kashmir are such that I cry when I see the photos of our house [even though] I have no recollection as I was too young when we fled,” said Wali. “I never faced any problem in Kashmir. Also, problems are part and parcel of life; it is better to ignore them.” He added that politicians should think beyond their own benefit. “The wise men of our community must find a way out. Everybody wants to return, but what would they do without housing and jobs?”

Ajay Raina, a civil engineer, is also not depending on the government. Two years ago, he bought land at Zewan on the outskirts of Srinagar to build a house and enrolled his two daughters in Delhi Public School, three kilometres from Zewan. “Some Kashmiri Pandit families are already living in Zewan,” he said. “The village also has a temple.”

He said he knew many Kashmiri Pandits willing to return, despite the perceived security threat. He added that, currently, several migrant Kashmiri Pandits in IT, pharmaceutical and travel companies rent houses in Kashmir for the summer and move out before winter. “There has been some impact of that (the killings of minority community members), but I do not feel threatened,” he said. “I feel safe in Kashmir. Once, some [outsider] colleagues and I ran into a protest, but after seeing me, they (protesters) let us go saying I was their bate boye (Pandit brother).”

An important facet of the return journey is the relations between the minority and majority communities in Kashmir. Ramesh Koul, a director at Kashmir Box, an online platform for Kashmiri-made products, said his perception of Kashmir changed after meeting two Kashmiri Muslims, Mehraj and Ishfaq, for a business proposal in Delhi in 2012. “When I met them, I felt as if I had returned to my roots,” he said. Koul said Kashmiri Pandits never felt insecure until the advent of the gun; he had left Pulwama in south Kashmir when he was in Class 7. Like most migrant Kashmiri Pandits, his family faced many hardships in Jammu, not least the heat. “It took us ten years to build a house in Jammu,” he said.

Through Mehraj and Ishfaq, he made friends with more Kashmiri Muslims. “I began to appreciate their side of the story,” he said. He now visits Kashmir often, sometimes with his family. “Whenever I visit Kashmir, I stay at my friends’ homes,” he said. “I enjoy working with Kashmir Box as it has reconnected me with my land.”

He said he knew several Kashmiri Pandits who had bought land in Kashmir to resettle there. “My kids’ education is holding me back for now,” he said. “After that, I will settle in Kashmir.”

The longing to return is more intense among the older Kashmiri Pandits. Rattan Lal (name changed), makes occasional trips to catch up with old friends and neighbours. He also joins the annual congregation at the Mata Kheer Bhawani temple in Ganderbal. “We used to live in a village at Qazigund in Anantnag before migration,” said the retired government employee. “Later, we sold some land because we needed the money. The rest of the land and our house is still there. The house needs some repairs, after which we will stay there in the summers. One of my sons is a chartered accountant; I want him to cater to clients in Kashmir, too.”

Ashok Tickoo, a retired ITC employee who had moved from Srinagar’s Habba Kadal to Jammu during the militancy, said he was optimistic about the Pandits’ return. “Our security is our Muslim brothers,” he said. “If the government makes arrangements, Kashmiri Pandits will return.”

Said Shivani Bakshi, who returned to Kashmir a few years ago: “Muslims also saved Pandits. Everyone is not the same. All Kashmiri Pandits should return.”

Bakshi used to live at Dal Hassanyar in Srinagar before they moved to Jammu. She now lives with her husband and children at Barzulla, an upscale locality in Srinagar, and works in the Union territory’s finance department. “I do not think I am working in a different environment,” she said.

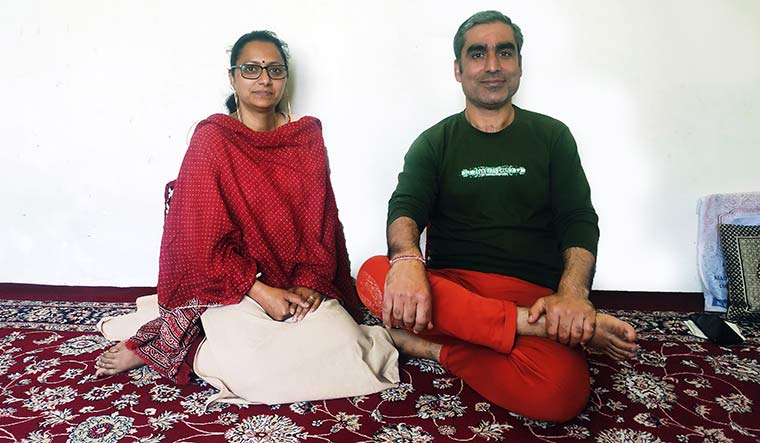

Like Bakshi, Nanji Dembi has also quietly returned. “We have been living a normal life here for eight years now,” he said. “We are originally from Tregham in Kupwara, but before we left for Jammu, we used to live at Chota Bazar, Karan Nagar in Srinagar, which is where we live now.”

Soon after his return from Jammu, his wife Rajni Kumari was elected sarpanch of Tregham. She has been allotted a flat in Srinagar. “Kashmir is safe. I request all migrant Kashmiri Pandits to ignore the propaganda about Kashmir and return to their homes and live peacefully,” said Kumari.

“I am the same Nane bate (short for Nanji) that my Muslim friends used to call me,” said Dembi. “We are all Kashmiris and we should all live together in harmony.”