Praful KhodaBHAI Patel, the administrator of Lakshadweep, on taking charge of the Union territory in December 2020, has set about producing drafts of regulations—the Lakshadweep Animal Preservation Regulation, the Lakshadweep Development Authority Regulation, the Lakshadweep Prevention of Anti-Social Activities Regulation (also called PASA or the goonda act elsewhere), and an amendment to the Lakshadweep Panchayat Staff Rules—that have generated widespread anxiety in the islands.

Claiming that there has been no development in Lakshadweep for the past 70 years, the administrator has proposed a cow slaughter ban in a territory where there are no cows, a preventive detention law where there is no crime, a draft law undermining tribal land ownership, ostensibly for land development, and plans for road widening on islands where the maximum road length is 11km. Patel’s occasional visits to the Union territory and the relaxation of quarantine restrictions have brought to Lakshadweep the deadly Covid pandemic, from which they had hitherto been free.

What does Patel mean by “development”? Lakshadweep today has rainwater harvesting facilities, accessible in every home. Solar power covers 10 per cent of lighting needs in the islands. All islands are connected by helicopter since 1986, and high-speed passenger boats—purchased in the 1990s on an international tender. A study by the National Institute of Oceanography had helped redesign the tripods reinforcing beaches against erosion. The islands have total literacy. Kadmat has a degree college and Agatti the Rajiv Gandhi Speciality Hospital. Minicoy has one of the earliest Navodaya Vidyalayas in the country. Kavaratti also has a wind-powered desalination plant.

Addressing the media in face of widespread criticism of these measures, Patel said he intends to develop Lakshadweep, like neighbouring Maldives, “a renowned international tourist destination”. Lakshadweep Collector Asker Ali said: “It was only in 2017 that the Centre constituted the Island Development Agency under the home minister for the development of the islands. Since then, we have been working on developing town and country planning norms.” The NITI Aayog in its report Transforming the Islands Through Creativity and Innovation (May 2019) called for Lakshadweep “to promote tourism in such a way, which is economically viable, environmentally sustainable, socially acceptable and culturally desirable”. Although the report is deeply flawed, as we shall see, in January 2020, the Government of India listed the islands in Lakshadweep for “holistic development” to promote tourism based on public-private partnership, and has offered facilities to export seafood and coconut products manufactured in the islands. Implementation of this programme is reported to have begun on five islands.

In 1988, a specially constituted Island Development Authority for the island territories of India, chaired by the prime minister, had approved a framework for the development of India’s island territories, accepting that “an environmentally sound strategy for both island groups hinges on better exploitation of marine resources coupled with much greater care in the use of land resources”. Opening Lakshadweep to international tourism was planned not as a means of generating wealth for investors from elsewhere, but for bringing prosperity to the islanders. Specifically rejecting the Maldives model for Lakshadweep the plan required that the tourism industry stay people-centric, and protect the fragile coral ecology.

The NITI Aayog report, however, declares that “the model [described in its report] may be replicated in other islands and also in other parts of the country”. This entirely contradicts the studies and research by outstanding environmentalists, including marine biologists, over the years that established that development paradigms for ecologically fragile island territories can never be even similar, let alone replicable.

Lakshadweep is an archipelago of coral atolls, whereas Andaman and Nicobar Islands are volcanic outcrops. Water villas—favoured by the NITI Aayog, and an expensive concept which is hazardous to corals—would collapse in Lakshadweep’s turbulent monsoon.

Given this background, the present administrator’s initiatives seem entirely misplaced, fulfilling no development needs, but threatening to disrupt and displace a peaceful tribal population.

(With extracts from Wajahat Habibullah: My Years with Rajiv: Triumph and Tragedy, Westland 2020)

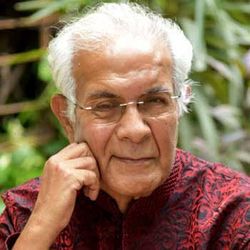

—Wajahat Habibullah was administrator of Lakshadweep from September 1987 to January 1990.