Temperatures in eastern Ladakh have dipped to -20 degrees Celsius, but the spirit of the Indian Army is soaring. Apart from keeping a check on enemy troops, Indian soldiers are guarding themselves from the fierce Himalayan winter.

Extreme winter clothing, sleeping bags, highly nutritious food, drinking water, kerosene—these are some of the basic items that soldiers in 8x8ft bunkers on the Rezang La heights need to survive. To fight, he needs compact battle kits containing weapons, ammunition and communication equipment.

With more than 50,000 troops deployed on the India-China border—the biggest such deployment since 1962—the Army is looking for ways to ride out the harsh winter. Defence scientists are offering multiple solutions to keep soldiers fighting fit for high-altitude warfare. Laboratories of the Defence Research and Development Organisation (DRDO) are looking at ways to reduce the acclimatisation period of troops and help soldiers keep themselves mentally and physically fit.

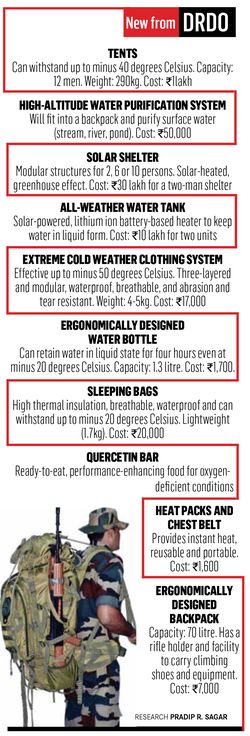

In early October, a team of DRDO scientists visited the Army’s 14 Corps headquarters in Leh. They proposed more than two dozen winter-gear accessories and other inventory that would help soldiers survive extreme weather conditions. The proposals include a high-altitude water purification system, oxygen-enriched shelters, space heating devices, sleeping bags that can be used at -50 degrees Celsius, high-nutrition quercetin bars and solar-powered shelters.

Ladakh has low oxygen levels and extreme weather. According to defence scientists, the atmosphere in eastern Ladakh, which is 15,000ft above sea level on an average, can have adverse physiological, psychological and hormonal affects that can lead to acute mountain sickness, high-altitude pulmonary oedema and high-altitude cerebral oedema. At present, the Army follows an 11-day acclimatisation regimen for its troops, done in three stages at different altitudes (9,000ft, 12,000ft and 15,000ft).

Though the Indian Army has four decades of experience in deployment in Siachen, the number of troops deployed there is much less than the deployment in Ladakh this time. Three new approaches have been proposed to the Army to reduce the acclimatisation period and speed up deployment. Prior deployment of soldiers at a moderate altitude, putting them through intermittent hypoxia (as training to survive in low-oxygen atmosphere) and providing oxygen shelters are the new methods.

Dr A.K. Singh, director-general of life sciences at DRDO, said maintaining optimal combat efficiency in extreme weather has for long been an objective for the Army. A similar rapid deployment, he said, was last attempted in 1999, during the Kargil war. “Our scientists are working with military doctors for enhancing troop acclimatisation by physical, physiological and psychological interventions,” said Dr Singh.

Indian and Chinese troops have been engaged in a standoff in Ladakh since May. The deployment of troops in eastern Ladakh is being done on the lines of the Siachen pattern—a 90-day deployment cycle before a soldier is replaced by another one. Military strategists believe that, with the trust deficit between the two sides, large-scale deployment of troops will be the new normal on the Line of Actual Control.

The Indian Army has just completed setting up habitats for troops in eastern Ladakh. But these habitats are only at the base camps, not at forward posts. Also, 11,000 sets of special winter clothing have been brought from the US. “Due to the unforeseen situation on the border, the Army had no option but to go for emergency purchase from foreign players. But we have the capability to produce such winter clothing,” said a DRDO scientist. “We are already in touch with the local industry to make it available. And we would be able to provide such clothing in the next six to eight months.”

The extreme winter clothing produced by the Defence Institute of Physiology and Allied Sciences (DIPAS) in Delhi is a three-layered modular system. Each kit weighs around 5kg. The clothing is waterproof, breathable, abrasion resistant and effective even in -50 degrees Celsius.

“It is almost one-fourth the cost of winter clothing that we import,” said the scientist. “All [extreme winter] clothing requires down feathers (fine bird feathers found under the tougher exterior feathers) to minimise heat transfer and keep it lightweight.” To tackle the issue of availability of feathers, scientists are exploring whether duck feathers can be used, since they are water repellent.

Another helpful tool is a space heating device that runs on kerosene. The devices are efficient and they do not release hazardous carbon monoxide. The Army has placed a Rs267-crore order for them.

To provide drinking water on icy heights, DIPAS has come out with a solar snow melter. Trials at Khardungla in Ladakh and Tawang found that these portable, manually operated snow melters are very helpful. “The issues faced by soldiers may not be new, but the scale is different this time,” said Singh. “All efforts have been made to cater to the requirements of the Indian Army, as the logistics burden has increased manifold.”

Defence scientists have set goals for themselves to develop new systems in the next few months. In the pipeline are modular garages for tanks, diesel generators that work at -50 degrees Celsius, solar-power shelters, rugged battery chargers, portable mobile cuboids and crevasse cross-bridges.

“Every solution cannot be a panacea for all problems,” said a defence scientist. “To meet future requirements, there is a need for more synergetic efforts between the DRDO, the armed forces and industrial partners, wherein the services and the industry view DRDO not only as developers, but also as their collaborative partners.”

An Army also marches on its stomach. A soldier needs to have around 4,500 calories a day to survive in high altitude. So the ration includes energy bars, chocolates, fruits and vegetables. O.P. Chaurasia, director of the Leh-based Defence Institute of High Altitude Research (DIHAR), says his laboratories are providing at least 28 types of vegetables to the Army. Set up after the 1962 war, DIHAR conducts research on agro-animal activities in extreme cold and high altitude. “In Ladakh, hydroponics (growing crops without soil) and micro-farming seem the only viable options,” said Chaurasia. “With this, limited quantity of fresh vegetables can be grown and it is developed to suit the Ladakh condition.”

Researchers at DIHAR have used their technology to grow vegetables like radish, broccoli and cabbage using low-intensity lights and limited amount of water. DIHAR scientists have also been researching on whether Bactrian camels in the Nubra valley, whose double humps can carry a load of 170kg, can be trained to transport ration and weapons. During the Kargil war, said Chaurasia, DIHAR researchers had successfully trained Zanskar ponies with the same objective.

Surviving in a bunker at -40 degrees Celsius is like living the life of a caveman, said Major General Amrit Pal Singh, former chief of operational logistics of 14 Corps. “We (the Army) are holding hilltops, peaks and clifflines. And you cannot carry stores to those points. You are actually living like a caveman by crawling into the hole and making a little warm space for yourself. Good clothing, nutritious food and frequent rotation to avoid physiological and psychological ailments are the only ways to protect the soldiers.”