IT WAS THE day after Valentine’s Day in 2012. The 11-member crew of the fishing boat St Antony had biryani left over from the previous day for lunch; they had cooked biryani to celebrate “lover’s day”.

Valentine Jalastine, 50, did not join the crew for lunch; he was fast asleep after pulling an all-nighter behind the wheel. He woke up at around 3pm, had lunch and took the helm again. “Jalastine asked me to take a break from steering,” said Freddy Bosco, owner of the vessel. “I was reluctant as he would have to be up again that night. But he insisted and I went to sleep.”

That decision saved Bosco’s life. For, barely an hour later, Jalastine was shot dead, allegedly by the security detail onboard the Enrica Lexie, an Italian oil tanker. “I woke up hearing a loud sound and saw Jalastine collapsing before me. There was blood all over,” recalled Bosco, 39.

Another round of firing soon followed. “I saw Ajesh Binki falling down,” said Bosco. “We all rushed to him. He asked for water, but died before he could drink it. He was barely 20.”

The crew members spotted the Enrica Lexie that was heading towards Kochi port. They also saw two men on it pointing guns at them. The men were reportedly identified as Italian marines Salvatore Girone and Massimiliano Latorre.

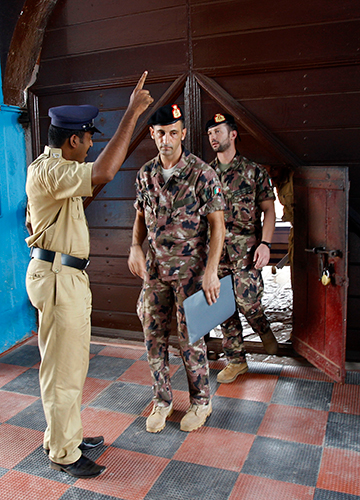

“All I knew then was that we needed to get away from them,” said Bosco. “I took the wheel and rushed to [Neendakara port, near Kollam], which was some six hours away.” The crew, meanwhile, alerted the Indian Coast Guard. The Enrica Lexie was soon intercepted by the Coast Guard and the Indian Navy; the marines were arrested by the Kerala Police for murder only on February 19.

The incident had led to a diplomatic tussle between India and Italy. India insisted that the killing happened in India’s exclusive economic zone, giving Indian courts jurisdiction. But Italy maintained that the incident happened in international waters and on an Italian ship, giving Italian courts jurisdiction.

The international legal battle ended on July 2, 2020, when The Hague-based Permanent Court of Arbitration Tribunal published its verdict. It ruled that the marines had violated international law, and as a result Italy had breached India’s freedom of navigation under the United Nations Convention on Law of Seas. New Delhi was entitled to get compensation, it added. But it also confirmed that the marines had immunity and could not be prosecuted in India.

“Does the verdict mean that rich men can get away with killings if they pay money?” asked Jalastine’s elder son Derrick. He was 16 when Jalastine was killed. “How did we lose a case that was foolproof? They need to be punished,” he said. “Those who milked the killings for political gains did nothing to win the case when they came to power.” Derrick was alluding to the BJP, which was then in the opposition. The party had raised a hue and cry over the issue, implicating Congress president Sonia Gandhi in the case because of her Italian roots.

Jalastine’s wife, Dora, said that initially the families of the marines would call them every Christmas and ask for forgiveness. “But there has been no contact for the last few years,” she said. She quickly added that the family was paid Rs1 crore compensation by Italy. “I educated my sons with that money, and built a house,” she said.

The payment of ‘blood money’ had created quite a furore then. The Italians were accused of using the Catholic Church in Kerala to get the families to withdraw the civil cases against the marines and the ship’s owner. The Kerala High Court had permitted the families to legalise an out-of-court settlement at the Lok Adalat, but the Supreme Court took exception, calling it a “direct challenge to the Indian judicial system”.

While the case was on in the Supreme Court, the two marines were allowed to travel to Italy to vote in the general election in February 2013. Later, Italy refused to send them back. This led to a huge diplomatic row. The Supreme Court then said that the Italian ambassador would not be allowed to leave the country unless the marines returned. This forced Italy to send the marines back. In 2014, Latorre was granted bail and allowed to go to Italy on medical grounds. Girone was granted conditional bail and permitted to go home in 2016.

The recent verdict has not given closure to the families. Dora is confused: “We don’t know whether the verdict is good or bad as some section of the media say it is a victory for India while others say we have lost the case.” But she is certain about one thing: “I will never send my children to sea ever.”

Ajesh Binki went to sea to provide for his two younger sisters. Natives of Kanyakumari, they were orphans. Both his sisters are now married and settled in Tamil Nadu. “He was the youngest one in my crew,” said Bosco. “He died on my lap. I can never forget that.”

The verdict has further dismayed him. Bosco had doggedly pursued the case against the marines in the Kerala High Court. He had also gone to The Hague to testify against them. “I was told by Indian diplomats and lawyers that we would win and that those two will be punished for killing my crew members,” he said.

The compensation aspect of the verdict, said Bosco, was something that the Italians had agreed to in 2012. “The whole case was an argument for punishing the Italians who had killed two poor fishermen,” he said. “If Jalastine had not insisted that I take rest on that horrible day, I would have been the one who was shot at. Not a single day passes by without me remembering that.”

Perhaps, in a bid to erase memories, the Enrica Lexie itself has changed hands, names and flags. It is now the Olympic Sky, owned by Athens-based Melodia Marine SA. Registered in Majuro, it now flies a Marshall Islands flag.