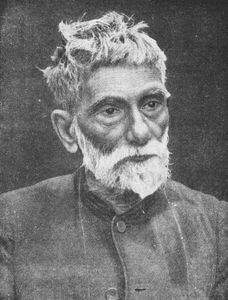

In 1901, the father of Indian chemistry, Acharya Prafulla Chandra Ray, founded India’s first pharma company, the Bengal Chemicals and Pharmaceuticals Ltd. The heart of the company was Ray’s own laboratory in his Manicktala residence in Calcutta, which he had set up nine years earlier for the princely sum of Rs700.

A few years before Ray converted his lab into a full-fledged company, a Calcutta-based British medical doctor named Ronald Ross had discovered that malaria was caused by parasites. A range of medicines to treat the disease were then invented, and Ray’s Bengal Chemicals soon became the first pharmaceutical company in Asia to mass-produce a version of the anti-malarial drug quinine.

The company kept growing until Ray died 1944. It began recording losses within a decade, ultimately leading to its nationalisation in 1980. By 1992, it had become so sick that the government had to intervene to restructure the company.

In 2016, though, the company turned a surprise profit of Rs4 crore. For the past four years, it has been on the recovery path. Now, as Covid-19 wreaks havoc across the world, Bengal Chemicals has become one of the most talked-about pharma companies in India.

The reason is that the West Bengal Directorate of Drug Control has issued the company a licence to manufacture hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), an anti-malarial drug that is believed to help Covid-19 patients recover faster. “For decades, we have been producing chloroquine phosphate [an anti-malarial drug], which is analogous to HCQ,” said a company spokesperson. “But, because of Covid-19, we sought a licence from the state government to produce HCQ and an approval from the Union government to manufacture the drug. We have received both.”

The swift approval owes a lot to US President Donald Trump, who recently forced India, the largest producer of HCQ in the world, to lift the ban on the drug’s export. The first two shipments of HCQ from India, manufactured by two Gujarat-based companies, have already reached the US. With Bengal Chemicals preparing to begin production, India would soon be able to increase exports and keep up with the domestic demand.

Several factors, however, could hamper the plans. Years of neglect have made it impossible for Bengal Chemicals to produce HCQ without sourcing ingredients from outside with the help of government agencies. “The ingredients of chloroquine phosphate and hydroxychloroquine are different,” said the spokesperson. “So we have written to both the Union and state governments to make the ingredients available.”

The state government is ready to help, on one condition. “We can give them the ingredients, provided that they give us around three lakh HCQ tablets a month,” said a health department official.

Apart from its facilities in Kolkata, Bengal Chemicals has factories in Maharashtra and Telangana. The governments there would also want their share of HCQ for helping the company source the ingredients.

Also, Bengal Chemicals will have to suspend production of all other drugs to start manufacturing HCQ. This means stopping the production of third-generation antibiotics, generic medicines and anti-viral drugs. “This is an emergency situation and we will have to be prepared for any eventuality,” said the spokesperson.

The HCQ project may not add to the company’s bottom line, as the Indian pharma regulatory system does not allow Bengal Chemicals to retail its products. “We can only sell our medicines to the Indian Army and government establishments like the Employees’ State Insurance Corporation,” said an official.

There are also fears that the whole undertaking would not yield the desired results. HCQ’s efficacy in fighting Covid-19 has not been clinically proven, even though doctors feel that the drug is helpful. There are fears of multiple side effects as well. HCQ can cause blurred vision, skin rashes, gastrointestinal issues and other adverse reactions.

“This medicine is very useful when we see the nature of the pathological damage that Covid-19 does to the human body,” said virologist Amitava Nandy. “The virus enters the cells and harms them, leading to multi-organ failure. HCQ prevents that to some extent. So, given the side effects it has, the medicine has the capacity to reduce the pathological damage as well as high level of inflammation in the body because of the infection.”

But how does HCQ really work? “It has the capacity to enter the cell, and its cytoplasm as well,” said Nandy. “It then changes the pH level of the sap inside the cytoplasm and raises its acidic level. Because of the increase in the acidity level inside the cytoplasm, the virus loses its capacity to damage the cell. The virus is also unable to multiply, thus reducing its lethality.”

Hospitals in several states have been giving HCQ to doctors and other medical staff as a preventive measure. Nandy, however, said it was not advisable. “This medicine is not used at the pre-exposure stage,” he said. “It can only work once the virus enters the cells. HCQ is recommended only after doctors, nurses and health care staff who come into contact with patients are infected. It can only be administered to patients who have full-blown Covid-19, and not at an early stage.”