Census 2027 is expected to set off a chain of political decisions with far-reaching consequences, including caste enumeration, constituency delimitation, women’s reservation and simultaneous elections. Together, these steps could redraw India’s electoral map, redistribute political power and force every major party to rethink how it selects candidates, builds coalitions and nurtures leadership

On April 1, the knock on the door will not be a prank.

On the other side will likely be a neighbourhood schoolteacher, trained to approach households with “a smile and proper salutation”, carrying a smartphone. That moment will mark the beginning of the biggest counting exercise on earth: Census 2027.

The enumerator will begin asking 33 questions which, for some, may feel like an exercise in self-discovery, covering both the structure of the house and the life inside it. She will record the material used for the floor, walls and roof; whether the house is owned or rented; and the number of rooms and the number of inhabitants. She will ask about the main source of drinking water, note the cooking fuel and source of lighting, and check whether the household has a kitchen and a bathroom. The caste of the family will also be recorded.

Other questions will include whether the household owns a television, a mobile phone or a smartphone, a computer or a laptop, and whether it has internet access. Ownership of a bicycle, two-wheeler or car will be logged, as will the main cereal consumed by the family. A mobile number will be collected for census-related communication.

For those with privacy concerns, the option of self-enumeration is available, allowing households to fill in the details on a web portal. This innovation makes Census 2027 India’s first fully digital census.

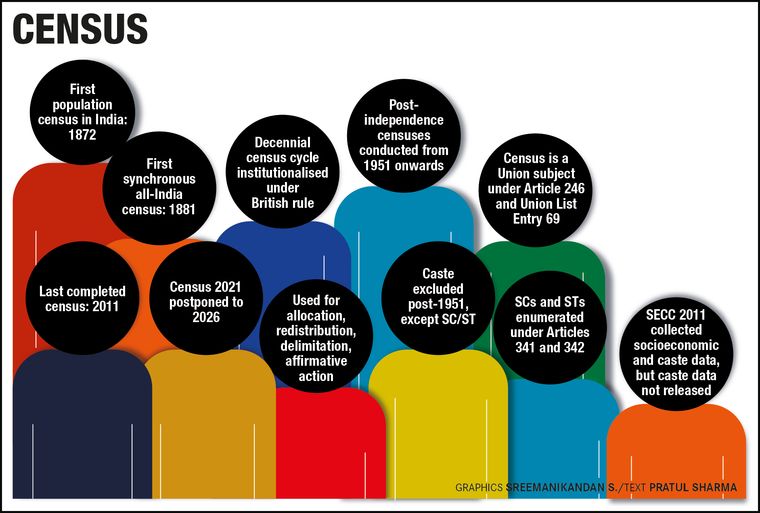

Although delayed by five years due to the pandemic—the first interruption in India’s census cycle since the exercise began in 1872—officials say analysis and publication will be significantly faster this time, given the shift away from paper. But unlike previous counts, Census 2027 will not be just about numbers. It may prove to be the most consequential enumeration exercise in independent India, with far-reaching political and social consequences.

It will set in motion four major decisions, arriving in sequence, each triggering the next, and together likely to change how India is governed and how society reorients itself. Embedded in the census is the recording of caste across India’s population for the first time in nearly a century, a step expected to intensify demands for proportional representation and higher quotas.

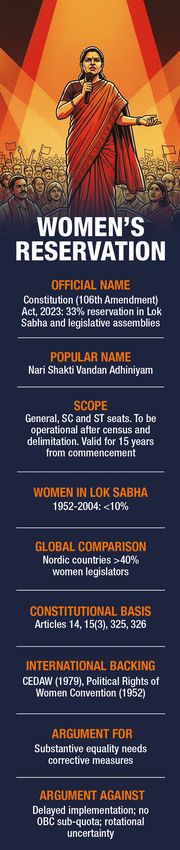

The next step has already triggered a deeply polarising debate: the delimitation of parliamentary and assembly seats. This exercise, in turn, will provide the basis for another defining move, the implementation of 33 per cent women’s reservation in Parliament and assemblies. In 2024, India elected 74 women MPs to the Lok Sabha. Even without an increase in the total number of seats, that figure could jump to around 180.

While these three processes are directly linked to the census, the next likely move after their completion, as pushed by the Narendra Modi government, is one nation, one election, synchronising Lok Sabha and assembly polls and fuelling concerns over federal rights. Taken together, these decisions will redraw India’s electoral map, redistribute political power and force every major party to rethink how it selects candidates, builds coalitions and nurtures leadership as India has entered the second quarter of the 21st century.

The caste census is likely to be the most disruptive element among these. It is a move expected to raise political temperatures, reviving anxieties among caste groups over representation, entitlements and relative power. India has already seen how sensitive the terrain can be. A backlash followed the now-paused University Grants Commission draft rules on discrimination, with the Supreme Court observing that the framework, in its proposed form, could deepen social divisions. Once fresh numbers are released after February 2027, mobilisation around new data is likely to translate into renewed demands for expanded quotas in government jobs and educational institutions, and potentially even in the private sector.

For the ruling BJP, the shift carries a complex political story. The party had long resisted a comprehensive caste census, while much of the opposition attempted to make enumeration a central electoral plank. That divide narrowed last April, when the Union government formally approved the inclusion of caste in the census, blunting the opposition’s main line of attack.

K. Laxman, BJP OBC Morcha president, Rajya Sabha MP and member of the party’s parliamentary board, described the decision as “bold and brave”. “Since 1931, no government has ventured to take such a step, despite regular demands. The BJP was never against a caste census,” he said, adding that digitisation would make the exercise a “game-changer”.

The opposition reads the government’s move differently. Congress leader Alka Lamba said the decision came only under sustained political pressure and that clarity on implementation was lacking. She cited the example of Telangana where a caste survey was conducted, and “communities were already seeing benefits”. She accused the Centre of diluting the exercise by sequencing caste enumeration alongside the general census and ahead of delimitation.

Across parties, there is broad acknowledgement that once caste numbers are public, pressure will mount to redistribute benefits across sub-groups. Laxman himself pointed to competing claims within the OBC category, where demands for sub-classification among “most backward” and “extremely backward” groups have intensified. “Depending upon the numbers and their socioeconomic conditions, the government would design welfare programmes and identify who has been left behind,” he said.

Behind these arguments lies a larger political risk. A caste census does not merely expand the data available for policymaking, it reshapes the terrain of politics itself. Fresh numbers could alter how coalitions are negotiated, particularly in the Hindi heartland. When delimitation eventually increases seats for populous states such as Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, the bargaining power of regional and caste-based parties could grow, forcing mainstream parties to recalibrate ticket distribution and alliances around demographic weight. Over the past decade, the BJP’s most powerful pitch has been hindutva, deployed as a unifying framework cutting across caste divisions. A detailed caste count, however, may reopen demands from communities that do not fit easily into broad ideological umbrellas.

There is scepticism within anti-caste scholarship about what enumeration can realistically achieve. Academic Anand Teltumbde, in his book The Caste Con Census, warns that enumeration risks reinforcing caste as the organising principle of governance. “Far from being a neutral data-gathering exercise, the census risks reinforcing caste consciousness, exacerbating social divisions rather than transcending them,” he writes. “A caste census does not simply reflect Indian society, it reshapes it.”

Within the BJP’s broader ideological ecosystem, the decision is also being read as a recalibration of how the RSS assesses social aspiration and political management. While the sangh appears to have accepted enumeration as a way to acknowledge competing demands, unease remains over its impact on internal cohesion.

Gautam Sen, professor at the London School of Economics and president of the World Association of Hindu Academicians, said he understood the political compulsions behind the decision, but warned of its social consequences. In his view, the impact “will not be good for Hindu society”, as caste counting could deepen fragmentation within the larger social framework.

If the caste census is expected to influence India’s polity and society for decades, another deep anxiety is already brewing in the southern states, where delimitation is widely seen as discriminatory. Delimitation has been frozen for nearly 50 years precisely because of this fear. Parliamentary constituencies have continued to be based on the population figures of the 1971 Census, even as India’s population has more than doubled. The freeze was a political bargain. States that invested early in education, health care and family planning would not be punished for controlling population growth. The Atal Bihari Vajpayee government reaffirmed this logic in 2001, extending the moratorium until 2026. Census 2027 points towards ending that suspension.

Once population figures are updated, seats will be redrawn and reallocated. A population-based formula will inevitably shift political power northwards, increasing representation for the Hindi heartland, particularly Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, while diminishing the relative influence of southern states where fertility rates have fallen much faster.

The anxiety has already spilled into political rhetoric. Southern leaders have urged citizens to have more children before March 1, 2027, the cut-off date for population enumeration. Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N. Chandrababu Naidu and Tamil Nadu Chief Minister M. K. Stalin have both publicly raised the issue, using provocation to underline what they see as an impending demographic penalty for states that followed the Union’s population control advice.

Sanjeer Alam, professor at the Centre for the Study of Developing Societies, describes the core issue as redistribution of seats across states. “Population growth rates have differed widely across states,” he said, producing a demographic imbalance that will quickly turn political. Southern states could lose close to one-fifth of their current share of Lok Sabha seats. Kerala could lose nearly six seats and Tamil Nadu, around nine. Uttar Pradesh could gain 12 seats and Bihar around 10. Such a shift, Alam said, would create “a serious regional imbalance in political power”.

DMK spokesperson Salem Dharanidharan framed the issue as a design failure the Constitution did not anticipate. “Delimitation is constitutionally mandated, yes. But the Constitution did not foresee the scale of population growth India would see after independence. Tamil Nadu’s total fertility rate is now under 1.5,” he said, pointing to decades of investment in education and health care. Globally, he argued, higher education levels among women are closely linked to lower birth rates.

Non-BJP parties in the south warn that post-delimitation arithmetic could fundamentally alter national politics. Based on the BJP’s 2019 performance in 10 Hindi-speaking states, where it won roughly 80 per cent of the seats, they argue that after expansion the party could form a government even if it failed to win a single seat from the remaining states. The fear is not hypothetical. It goes to the heart of whether southern states will retain any meaningful influence over national decision-making.

The BJP’s response has been reassurance, coupled with insistence that the process cannot be postponed. Vanathi Srinivasan, national president of the BJP Mahila Morcha and MLA from Coimbatore South constituency, acknowledged the anxiety. “There is a genuine concern,” she said. “Southern states who have followed family planning and development initiatives should not feel they have been penalised.”

At the same time, she defended delimitation as unavoidable. “The delimitation process is not a government decision or a political promise,” she said. “It is mandated by the Constitution.” She said the Centre was aware of regional concerns and that ministers had assured states that no seats would be lost. Laxman was more categorical. “[Union Home Minister] Amit Shah ji has made it very clear. We will never allow the south to lose seats. Not even a single seat will be reduced,” he said. Any increase, he argued, would be proportionate and southern states would not be discriminated against.

But the dispute is not about whether seats decrease in absolute terms. It is about relative share and influence. Even without seat loss, dilution of political weight remains the central concern.

Despite these anxieties, the case for delimitation is also strong. Representation gaps have widened sharply. Sikkim has one MP for roughly five lakh people, while some constituencies elsewhere have more than 40 lakh voters. In 1976, the average Lok Sabha constituency represented about 10 lakh people. Today, that figure has ballooned, turning MPs into distant figures with limited capacity to represent constituents effectively.

How to update representation without turning it into a permanent north–south clash is the unresolved challenge. Several options are being discussed, none without problems. One is to extend the freeze yet again. Another is to expand Parliament so that one MP represents around 10 lakh people. A third proposal is to significantly increase the number of MLAs within states, since governance decisions are largely taken in state capitals. Some argue that if the Lok Sabha remains population-based, the Rajya Sabha should better reflect economic contribution or development, though this would require constitutional changes and broad political agreement.

Alam’s own proposal is narrower: use the adult population rather than total population as the basis for delimitation. He said that would distribute gains and losses more evenly and prevent extreme regional concentration of power.

On the ground, delimitation will be disruptive. Redrawn boundaries will displace sitting MPs, unsettle entrenched networks and produce political losers before winners emerge.

Once the formula for delimitation is devised and seats are redrawn, the long-awaited reform that witnessed rare political unanimity in September 2023 is expected to finally come into force. It has remained pending precisely because delimitation must precede it. The 33 per cent reservation for women was won after a long and often bruising struggle by women activists and politicians against deeply entrenched resistance to sharing power.

Women’s rights activist Ranjana Kumari recalls the effort that went into building momentum for the reform. In the mid-2000s, a group of women activists undertook a train journey known as the Chetna Yatra to mobilise public opinion across the country. “At railway stations, we rolled out a long cloth on the platform and collected signatures from whoever was passing through,” she said. “Sometimes there was no one at the station, so we garlanded ourselves. We spoke to anyone who would listen. When the journey ended, we submitted the signatures to the president, A.P. J. Abdul Kalam.”

Srinivasan said the idea itself was never radical, only delayed. “As far as the assemblies and Parliament are concerned, the bill was pending for a very long time. Political parties spoke about women’s reservation, but nothing happened. It was only because of the political will of the Modi government that it finally happened.” Despite the celebratory language around the law, many political parties remain unprepared for its consequences.

In an expanded house after delimitation, the number of reserved seats could cross 280. Across assemblies, more than 1,300 seats would be reserved for women. This would directly translate into more women entering cabinets, expanding the leadership pipeline and reshaping who eventually occupies the offices of chief minister and prime minister. When the quota is implemented, political parties will be forced to manage two disruptions simultaneously: a radically altered electoral map after delimitation and the compulsory nomination of women in one-third of constituencies.

Most parties are not structurally built for this. Candidate selection remains male-dominated. Party hierarchies are controlled overwhelmingly by men. Even after the law was passed, scepticism persists over whether there are “enough women leaders” to fill the seats. “Women are always ready,” Kumari said. “Look at city mayors. Now 30 to 40 per cent are women. Women are visible everywhere, from municipal offices to universities and corporate boards. When the law is implemented, women will be ready to step in. The problem lies with political parties.”

Srinivasan said the BJP was ahead of its rivals because it institutionalised women’s representation long before the law was passed. “We are the only political party in India that gives 33 per cent reservation within the party structure, from the booth level to the national level,” she said, and added that the system had been in place for over two decades. That structure, she said, enabled women to rise without dynastic backing.

Srinivasan pointed to local bodies as a training ground. With reservation in panchayats and municipal bodies, women have already accumulated political experience and altered governance priorities. “When women are in power,” she said, “sanitation, public health, and drinking water are the main areas that get attention.” She also argued that women now handled major portfolios at the national level. “We can see how Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman is performing.”

Lamba made the opposite case. She said the government acted under sustained political pressure and remained reluctant about actual implementation. “We kept continuous pressure on the government. Just before the 2024 Lok Sabha elections, pressure peaked and they were forced to act.”

The core question remains unresolved: who will parties field once reservation becomes compulsory? Critics argue that women’s reservation will disproportionately benefit political families, bringing more wives and daughters into legislatures. Srinivasan put the blame on the opposition parties for dynastic politics. She also pointed towards the double standards. “When men contest because of family background, no one questions it. When women do, suddenly conscience awakens.” Kumari, too, backed the charge of selective scrutiny. “Many male MPs have spent five years in Parliament without speaking or contributing,” she said. “But when it comes to women, standards are suddenly raised.”

Privately, several male MPs conceded that family members might be fielded when seats become reserved. That has revived fears of the return of the sarpanch-pati phenomenon, where elected women are seen as proxies for male relatives. Kumari dismissed the comparison. “Parliament and national assemblies are not spaces where someone can be controlled from behind,” she said.

There is, however, another structural challenge embedded in the law: rotation. Reserved seats will rotate across constituencies, meaning a woman MP could win a seat and still be unable to contest from it again. Rotation was designed to prevent capture. It may also discourage long-term constituency investment.

Alam said women MPs might hesitate to build deep local networks if they knew their seat would rotate away. Parties, too, will face conflict over who gets which constituency and for how long. He pointed to alternatives, including dual-member constituencies where one man and one woman were elected from the same seat, a model India experimented with in the 1950s and 1960s.

The combined impact of the caste census, delimitation and women’s reservation is likely to become visible by the 2029 Lok Sabha elections, unless the Centre yields to southern states’ demands to extend the freeze on delimitation. But political planning has already begun with an eye on 2034, when the government may attempt its most ambitious institutional reform yet: one nation, one election. Laxman framed it as a governance imperative. Citizens want elections in a “single stroke”, he said, because repeated polls drained money, workforce and administrative attention. Government machinery is perpetually locked into election duty. The model code of conduct freezes development.

Supporters of simultaneous polls argue that poorer families suffer the most during repeated elections. Government schools and hospitals depend on public staff who are routinely diverted for election duty. With improved technology, Laxman said, elections could now be managed together.

Also Read

- Counting caste to counter caste: The politics of enumeration in modern India

- The delimitation dilemma: Why India's north-south divide is at a breaking point

- Nari Shakti Vandan Adhiniyam: Progressive law or a 15-year setback?

- One Nation, One Election: India's solution for reform or a democratic risk?

Politically, one nation, one election would reward parties with strong organisational dominance and national presence. By compressing electoral contests into a single national cycle, it would reduce regional churn and amplify national narratives, weakening the leverage of state-specific political voices.

Lamba rejected the proposal outright. “We have taken a clear stand in the Congress Working Committee,” she said. “We are against this concept. In a country of 140 crore people, one nation, one election cannot be conducted. Panchayats, municipalities, MLAs, MPs, MLCs—everything cannot be done together. It is against federalism.” Even some BJP allies have remained cautious, fearing erosion of regional autonomy.

The transitions embedded within Census 2027 promise changes far deeper than the public debate currently reflects. While anxieties are evident among political elites and policy circles, large sections of society and even political leadership remain disengaged from the scale of what is coming. India has navigated upheavals before: linguistic reorganisation, the expansion of reservations, the Mandal reforms. Each triggered instability before settling into a new equilibrium. This transition, however, is different in scale and design. It is stacked—one reform triggering another, each reshaping the next.

The challenge ahead is not merely implementation, but dialogue. Without sustained political engagement, the coming churn risks turning a structural reform into a prolonged conflict.