Few issues are as politically explosive—and as constitutionally consequential—as the coming delimitation of Lok Sabha constituencies. For most Indians, “delimitation” is a distant technical term, but many consider it nothing less than a redistribution of political power among states. It is the moment when India redraws the map of democracy. Done right, it can renew faith in federalism; done wrong, it can deepen regional fault lines.

The constitutional provision

Article 82 of the Constitution provides that, after every census, Parliament shall enact a delimitation act and set up a delimitation commission to readjust the allocation of seats in the Lok Sabha and assemblies. The underlying idea was to ensure that the house reflects population shifts and that every MP represents roughly equal numbers of citizens.

But this ideal was challenged by the demographic reality of India. Some states—notably those in the south—implemented aggressive family planning and achieved population control. Others, particularly in the Hindi heartland, continued to see high growth. If we had simply applied Article 82 strictly after every census, the better-performing states would have lost seats, and the high-growth states would have gained them.

A historic compromise

To prevent such an undesirable outcome, Parliament enacted the 42nd Amendment in 1976, freezing the allocation of seats at 1971 census levels. This was more than a technical adjustment—it was a moral commitment: That states would not be punished for doing what the Union had asked them to do.

The 2002 extension

When the freeze was due to expire after the 2001 census, Parliament reviewed the issue. By then, the gap between high-fertility and low-fertility states had narrowed but not disappeared. Parliament decided that the rationale still held. Through the 84th Amendment, it extended the freeze until after the first census held post-2026—effectively postponing delimitation until 2031. In the accompanying resolution, Parliament effectively reaffirmed that equity among states was more important than mechanical equality of population numbers.

Why the logic still holds

The reasons that justified the freeze in 1976 and 2002 remain compelling even today. In fact, the disparities have only become more politically sensitive. Southern states, along with a few others like Punjab and West Bengal, continue to have lower fertility rates and higher social indicators. To reward them with fewer MPs now would not just penalise performance, it would weaken the incentive structure that underpins our population policy.

More importantly, federalism is not merely arithmetic. India is a Union of states which recognises that national integration requires a balance between the large and the small, the populous and the less populous.

The debate and south Indian fears

As the next round of delimitation approaches, these fears have come roaring back. Tamil Nadu, Kerala, Karnataka and Telangana have voiced concern that their seat share in Parliament will shrink if allocation is based on current population. Tamil Nadu has even convened a joint action committee with other affected states to demand “fair delimitation”. But what is “fair” is yet to be spelt out.

The government has offered to retain the existing proportion of seats—that is, to freeze the relative share of each state and merely increase the absolute number of MPs in proportion. This assurance seems to address the southern concerns.

But, a closer look shows it does not solve the core problem.

A possibility to remember is that after the reservation of seats for women is implemented, the size of the Lok Sabha is likely to increase. As also if the population is taken as the basis.

The problem of absolute numbers

Representation in Parliament is not about percentages; it is about the number of votes. If Tamil Nadu’s proportion remains at 7.2 per cent, its MPs may rise from 39 to roughly 64 in an 888-member house (figure quoted in Rajya Sabha debates). But, Uttar Pradesh’s MPs will simultaneously rise from 80 to about 131. The absolute vote gap between Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu will widen from 41 to 67. If delimitation uses current population numbers, the gap could widen even more—to nearly 94.

In a house where each MP casts one vote, this means the Hindi heartland will have an even greater ability to push through legislation—from budgets to constitutional amendments—with or without the consent of the southern states.

Also Read

This is not merely a southern grievance. It is a concern for federal stability. If large sections of the country feel politically disempowered, the centrifugal pressures on the Union will grow stronger.

What, then, is the way forward? Simply expanding Parliament without adjusting the federal balance is not enough. The most logical solution is to continue the 1971 baseline, at least for one more cycle.

Delimitation is not a mere cartographic exercise—it is a constitutional moment. The framers of the 42nd and 84th Amendments recognised that India’s unity required fairness, not just arithmetic equality. That logic is valid—perhaps even more urgent—in 2025.

If we ignore it, we risk deepening the already visible north-south divide and undermining the sense of partnership that holds this Union together. The challenge before us is to ensure that the next delimitation renews India’s federal compact instead of fracturing it. That requires courage, imagination and a willingness to think beyond the numbers. In the absence of a feasible alternative proposal, the government’s assurance seems to be the most viable solution.

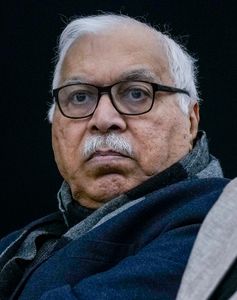

The writer is former chief election commissioner and the author of a number of books on democracy, the latest being Democracy’s Heartland: Inside the Battle for Power in South Asia.