JAMMU AND KASHMIR AND DELHI

A BROKEN CONCRETE slab tangled with destroyed wooden planks is what remains of Ahsan ul-Haq Sheikh’s house. A few steps away, his aunt Imtiaza’s house stands upright, but has visible damage. “There was a thunderous blast,” said Imtiaza, “which shook the neighbourhood houses and shattered all our windows.”

Sheikh is one of the 13 people whose houses were razed after security forces cracked down on Pakistan-based Lashkar-e-Taiba operatives in the wake of the Pahalgam attack. The police has cordoned off Sheikh’s colony―about 50 houses―in Pulwama district’s Murran village. It is about 30km from Srinagar.

The neighbours have not seen Sheikh for the past two years; police claim he joined the LeT in June 2023. Sheikh’s paternal uncle, Mohammad Shafi, said Sheikh’s parents had left the place after he did not return. “When he left, his mother’s heart disease worsened,” he said. “God knows where they are.”

Sheikh, 23, had participated in protests after the killing of separatist leader Burhan Wani in 2016. “His parents tried so hard to reach out to him, but they could never know where he is,” said an elderly woman in the locality. Like in most such cases, the villagers know nothing more―once a boy disappears, they assume he has joined the militants or has been killed.

Police say the average lifespan of a terror recruit is six months to a year. Once he carries out a terrorist act, he is chased by security forces and many a time he is offered up by terror masters who spill blood to keep the pot boiling.

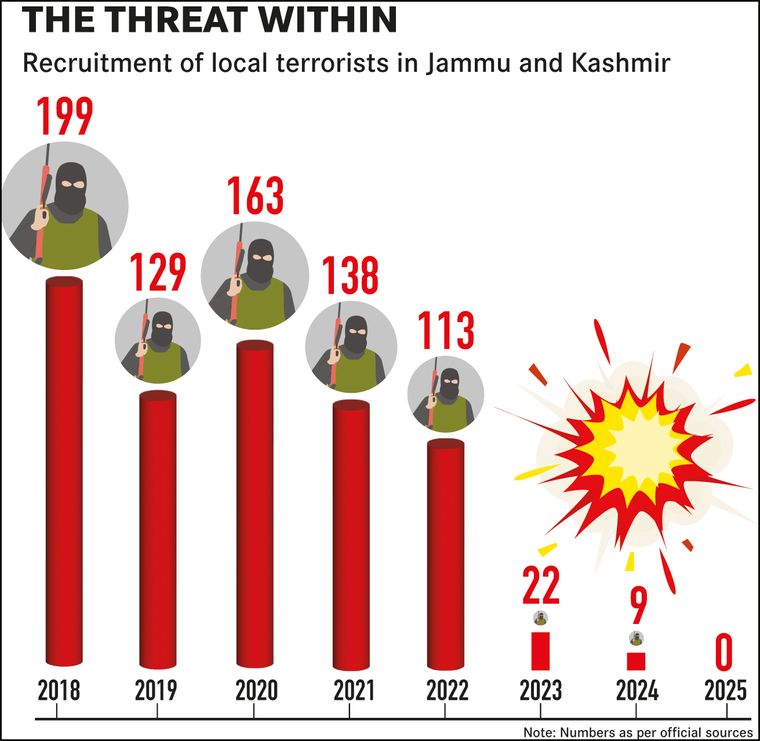

The Pahalgam attack is a classic example of the terrorist ecosystem―a network of militants, ideologues and handlers resorting to desperate acts, seeking attention through bloodshed rather than ideology. R.R. Swain, former director general of Jammu and Kashmir Police, who spent years dismantling the terror ecosystem, said the decline in local recruitment has significantly impacted terrorist operations. “In 2018, 199 local boys had joined terrorist outfits,” he said. “After the abrogation of Article 370 in 2019, the numbers began to dwindle―almost 138 in 2021, 113 in 2022, 22 in 2023, and nine in 2024. In 2025, we saw zero local recruitment.”

This collapse, Swain believes, triggered the Pahalgam attack. In a last-ditch effort, they targeted something Kashmiris hold dear: tourism.

Terrorists have long thrived on narratives of resistance, but that is now eroding. “They have lost the support of the local population, and they know it,” said Swain. “So, instead of gaining ground, they have been resorting to desperation.”

Terror groups have also tried to gain political acceptance over the years, but now, as their influence wanes, they find themselves increasingly marginalised. “Anything that brings normalcy to the region―tourism, infrastructure, integration with India―threatens their existence,” said Swain. “Pahalgam was symbolic. The more peaceful and integrated Kashmir becomes, the more irrelevant they feel.”

What is new is the terrorists’ willingness to burn bridges with the masses to stay relevant. During an interrogation of a terrorist years ago, Swain was struck by a chilling statement: “I can live with being hated, but I don’t want to be forgotten.”

Swain believes Baisaran was targeted because it was seen as a symbol of growing peace. “They had to strike where they could make the loudest noise,” he said.

Security officials said the attackers’ intentionally kept the death toll “in control” to avoid global backlash. “They wanted to make enough of an impact to disturb the security establishment, but not so much that it would lead to major international retribution,” said a senior officer.

But escalation is imminent. Prime Minister Narendra Modi, with trusted lieutenants Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and Union Home Minister Amit Shah, has green-lit a sharp response―National Security Adviser Ajit Doval, along with the military chiefs, is strategising counter-terror operations behind closed doors.

The decision has been taken after a deep understanding of the changing dynamics in Pakistan’s approach toward Kashmir. General Qamar Javed Bajwa, former Pakistan army chief, had been seeking engagement with India, but his successor, General Asim Munir, seems intent on intensifying the proxy war.

The reasons are manifold. Global isolation, economic pressures and the resurgence of the Tehrik-e-Taliban Pakistan has been coupled with trouble in Balochistan, where the state has incarcerated peaceful activists and shut down the internet.

“Pakistani authorities were quick to blame India for the hijacking of the Jaffar Express on March 11, while failing to acknowledge the swelling numbers of highly educated Baloch youth taking up arms,” said Prateek Sinha, a PhD in modern history from the University of Oxford. “The new face of Baloch resentment is no longer confined to the tribal chieftains. It embraces cosmopolitanism and possesses a deep knowledge of Baloch history.”

The past few years have also seen a convergence of voices from Balochistan and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, which question the growing militarisation and the virtual absence of civilian institutions. “The resentment begs a larger question tied in with their complicated integration into Pakistan in 1947,” said Sinha.

As for India’s response, multiple arms of the government are on the task. The Jammu and Kashmir Police are identifying local aides of terrorists and Indian troops are swiftly retaliating to unprovoked firing on the borders. They are also keeping Pakistani forces engaged till technical intelligence agencies identify and isolate non-state actors like the ideologues and top brass of terror outfits. Once operational markers like terror coordinates are with security agencies, it is only a matter of where, when and how? It could be targeted strikes on key terror ideologues or a strike on larger terror camps of footsoldiers in Pakistan-occupied Kashmir. Lastly, India is also ready with its diplomatic offensive to expose Pakistan’s continued support to terror.

“The LeT and its proxies are the target this time,” said sources in the Jammu and Kashmir Police, while admitting that their original affiliations had been masked by the fluidity of terrorists moving between the near 40 terror launch pads across the Line of Control.

There is another step to the counter-terror action―a civil society outreach by the government to unite people against terror. Whether it is Modi’s Mann ki Baat or small processions in states to stand in solidarity with the Pahalgam victims, the attempt is to ensure that the integration of Jammu and Kashmir is complete. “With bodies of tourists reaching states like Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra, Karnataka and Gujarat, there is unity in rage and revulsion,” said Tilak Devasher, former member of the National Security Advisory Board.

Debasish Bhattacharya, a 56-year-old professor at Assam University in Silchar, recalled how one of the terrorists came menacingly towards him. “These were the longest few seconds of my life,” he said. “After the gunshot sounds, my son tugged at my arm in panic saying he saw the man―who was shooting at tourists about 20 metres away―coming towards us.” They ran towards some trees and hid. “For the next two hours or so,” he said, “we kept moving with no sense of direction but followed a pony track as we knew it would lead us somewhere. We had to drink the dirty water left in puddles made by the hooves of the ponies.”

Devasher said all right-minded nations had condemned the attack, putting pressure on Islamabad. “Even the Taliban has condemned it,” he said. There might be internal issues in Afghanistan, but its assertion that it will not be comfortable with Pakistan’s continued support to cross-border terrorist outfits has given India’s response a shot in the arm. There is an urgency in India’s assertion of its sovereignty over Jammu and Kashmir, especially after the abrogation of Article 370, which is why a stern message to Pakistan is being calibrated.

Delhi’s move of cancelling Pakistani visas and holding the Indus Waters Treaty in abeyance prompted Pakistan to threaten to suspend the 1972 Simla Agreement. This indicates that tensions will not ease soon. The Simla Agreement governs the Line of Control, and any threat to it can result in serious escalation. Consequently, more questions are being raised behind closed doors about the relevance of the United Nations Military Observer Group, set up to monitor the ceasefire line.

Back in the Union territory, there is growing consensus that the assembly seats reserved for PoK-displaced residents must be filled to blunt the terrorists’ narrative. A small match can light a huge fire. This time, it was the entry of tourists and labourers from other parts of the country to participate in building a new Kashmir. “No tourist who goes to Jammu and Kashmir plans to settle down,” said Swain. “Even the locals know that and are happy to receive them. But the narrative that tourism was another attempt to change the demography gave a signal to the terror masterminds to fan the flame till it became a fire.”

In the past six months, terror attacks in Gagangeer, Gulmarg and now Pahalgam corroborate the National Investigation Agency’s suspicion that it was a larger cross-border conspiracy. “Local aides of terrorists need to be examined to unravel cross-border movements and identify common conspirators,” said Atulchandra Kulkarni, former NIA special director general, referring to the killing of seven civilians working at a construction site in Ganderbal district’s Gagangeer last October. The same month, terrorists targeted an Indian Army vehicle near Gulmarg, killing soldiers and porters. “The technical evidence from terrorists killed in December shows that the Gagangeer and Gulmarg module was also active in Pahalgam,” said an investigator.

The NIA is retracing the steps of the terrorists to investigate the gaps they exploited. Police officers admitted that there was a lack of area domination, especially in places like Pahalgam, which was considered relatively peaceful.

Area domination refers to the strategic deployment of troops across an area to maintain control, deter hostile activities and ensure immediate response in case of a security breach.

Also Read

- 'India is preparing to meet multi-domain threats': Rajnath Singh to THE WEEK

- 'India should combine firmness against external threats with compassion, foresight in Kashmir'

- India's military preparedness and challenges: What ex-chiefs of Army, Navy, Air Force say

- How China can assist Pakistan in aftermath of Pahalgam terror attack

- Why Pakistan army chief Asim Munir is raising tensions with India

- 'Countries fighting terrorism, radicalism quick to identify with India over Pahalgam'

“When there is less intelligence or when inputs are limited, it becomes crucial to ensure more robust deployments,” said K. Srinivasan, former inspector-general (intelligence) who has served in the Border Security Force and the Central Reserve Police Force. “The military and police need to reinforce their presence, not only as a deterrent, but also to act swiftly if an attack takes place.”

Though the spiralling of tension with China after the Galwan valley clashes in 2020 saw a realignment of troops, the needs of both the western and eastern sector were being balanced well. The balance has tipped over for now, but efforts are on to restore it. “Terror is on its last legs in Jammu and Kashmir,” said a senior state police officer. “Work is on to dismantle the terror infrastructure. It was neither built in a day nor can it be destroyed in a day.”

―With inputs from Sanjib Kr Baruah