Dholera, Gujarat

Located 115 kilometres southwest of Ahmedabad, Dholera is a dusty village of broken roads and rugged terrain―nondescript at first glance. The landscape is dry and barren, save for an area where construction is in full swing. Sleek office buildings are beginning to rise, and newly laid blacktop roads carve paths into the future―an empty canvas coming to life.

So far, 22 square kilometres have been developed―the first brushstroke in an audacious plan to transform Dholera into a next-generation city. Over the next three decades, under the Dholera Special Investment Region (DSIR) project, 22 villages in the taluka will be woven into a sprawling, 920sqkm megacity―larger than Mumbai or Bengaluru.

This transformation is being charted through six town-planning schemes (TPS), rolled out in three phases. Phase one includes TPS-1 and TPS-2, covering 158 square kilometres. This phase involves building essential infrastructure: roads, utility grids, water pipelines, wastewater systems, solid waste facilities, and power and information technology networks. Also under development is a river-bunding project, the Ahmedabad-Dholera expressway, freight and rapid transit rail links, and an international airport. Since Dholera falls within a coastal regulation zone, 150 square kilometres of agricultural land will remain preserved.

As a greenfield city-in-the-making, Dholera is envisioned as a manufacturing and industrial hub. Its economic base is set to shift from agriculture and aquaculture to high-value, cutting-edge sectors such as electronics, aviation, defence, metallurgy, pharmaceuticals, biotechnology, automotive components, and agro-food processing.

Among all the developments, perhaps the most ambitious is the Rs91,000-crore plan to build India’s first commercial semiconductor fabrication plant―a cornerstone of technological self-reliance. Spanning 290 acres and encircled by a protective canal that would prevent floods, the facility is being developed by Tata Electronics in collaboration with Taiwan’s Powerchip Semiconductor Manufacturing Corporation.

Creating a semiconductor chip is arguably as complex and demanding as building an entire city from scratch. Often cited as the most intricate human-made products, chips are the invisible engines of the digital age. They power everything from smartphones and automobiles to advanced medical systems and military technology. With the rise of artificial intelligence, chips have become the most strategically valuable asset a nation can possess.

Yet, India remains a marginal player in the global semiconductor arena. The country lacks a commercial fabrication facility, forcing it to continue importing 95 per cent of its chips from China, Taiwan, South Korea and Singapore. In 2023-24, India imported 18.43 billion chips and ‘system on chips’ (SoCs, which combine essential parts such as processor and memory onto a single chip) worth $20.7 billion.

India realised the urgent need to change course because of two pivotal events: the Covid-19 pandemic and a border standoff with China. “Back in April 2020, the government moved to restrict opportunistic takeovers of Indian companies by entities from countries it shares land border with. It was widely understood that the policy was aimed at Chinese firms,” said Konark Bhandari, a Carnegie India fellow who authored the paper Geopolitics of the Semiconductor Industry and India’s Place in It.

Following the border tensions, India ramped up its pushback―banning hundreds of Chinese apps in June 2020 and, a year later, barring Chinese telecom giant Huawei from participating in 5G trials. “By June 2021, India had also barred Huawei from supplying equipment to mobile carriers,” Bhandari said. A former official of the Competition Commission of India (CCI), he specialises in space tech regulation and digital antitrust policy.

While the pandemic exposed the fragility of global chip supply chains, the border standoff underscored the strategic perils of dependency on China. With India’s semiconductor market booming―it is expected to surpass $80 billion by 2026 and $110 billion by 2030, according to the US department of commerce―there is a greater urgency to build a robust domestic manufacturing ecosystem.

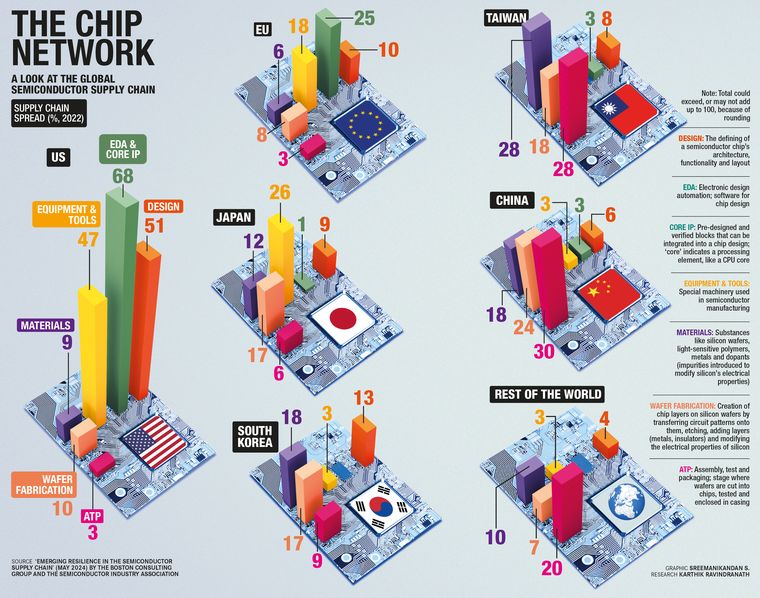

The global chip shortage revealed how deeply interconnected, and vulnerable, the semiconductor supply chain is. With no single entity in full control, semiconductor manufacturing is a symphony of global inputs: lithography machines from the Netherlands, specialty gases from Japan, and fabrication hubs in Taiwan and South Korea. A single tremor―an earthquake in Japan or a drought in Taiwan―can send shockwaves through the global economy.

As artificial intelligence and machine learning redefine the boundaries of computing, cutting-edge chips have become essentials. Driven by the demand for AI integration, internet of things, and ever-smaller consumer electronics, India can no longer afford to rely solely on imports. The message is clear: if India wants to stay relevant in the digital century, it must secure its semiconductor future.

With the fab being built in Dholera, India’s semiconductor dream is waiting for its breakthrough moment.

India’s semiconductor foray began in 1962, when Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL) started producing germanium transistors. By 1967, the company had progressed to silicon-based devices, marking a significant shift. But, even as India refined transistor technology, the world swiftly transitioned to integrated circuits (ICs)―compact chips that combined transistors, resistors and capacitors into a single unit.

BEL eventually ventured into IC manufacturing, but the progress was sluggish. It was not until the 1980s that the sector gained traction, fuelled by a $40 million investment from the government to establish Semiconductor Complex Limited (SCL) in Mohali, Punjab―India’s first semiconductor fabrication facility. Streamlining licensing regulations and reducing import duties, the government set the stage for accelerated growth. Remarkably, this happened before Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC)―now a global leader―even entered the industry.

By the late 1980s, SCL had advanced to 800-nanometre technology―the number referring to the width of the chip circuit line. The gap with global standards was down to just two years.

“But they were not producing large-volume commercial chips, which were the trendsetters in the advancement of semiconductor manufacturing at that time. The Indian market was very small and they did not have any export market,” said Pranay Kotasthane, deputy director at the Takshashila Institution and author of When The Chips are Down: A Deep Dive into a Global Crisis.

According to Kotasthane, the state-controlled, non-competitive environment hindered government companies. India’s semiconductor industry soon ran into a major challenge: Rock’s law, which says the cost of semiconductor fabrication plants doubles every four years. As it became increasingly expensive to remain competitive, and without a sustained growth in investment from the government, there was a gradual decline in India’s semiconductor ambitions.

“Government-run companies struggled to keep pace with the rapidly evolving semiconductor industry, largely because they operated in a non-competitive environment that didn’t demand continuous technological upgrades. The companies were also restricted from competing with each other,” said Kotasthane.

While SCL was tasked with chip manufacturing, BEL was restricted to assembly, creating a fragmented approach that stifled innovation. As a result, both failed to keep up with Moore’s law―the principle that transistor density in integrated circuits doubles roughly every two years, fuelling exponential advancements in computing power and efficiency.

A devastating fire at SCL’s Mohali facility in 1989 further pushed India behind, as the US, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea marched ahead. While the SCL and BEL continued to serve government agencies such as the Defence Research Development Organisation, the Indian government in 2007 unsuccessfully tried to attract private players in semiconductor manufacturing by offering a host of incentives, including capital subsidy of up to 25 per cent.

Over the years, several semiconductor projects to address India’s commercial needs were proposed only to fizzle out later. The Andhra Pradesh government’s ‘Fab City’ project, announced in 2006, failed after major investors SemIndia and Nano Tech Silicon India backed out following the global financial crisis. Infrastructure firm JP Associates, in association with IBM and Israel’s Tower Semiconductor, wanted to build a wafer fab in Noida. But they abandoned the plan in 2016, saying it would not be commercially viable.

With high-profile proposals not progressing beyond the drawing board, India continues to rely on imports. In 2021, realising the need to secure India’s technological future, the government launched the India Semiconductor Mission (ISM) as an independent division within Digital India Corporation, a not-for-profit company established in 2013 for capacity building in technology. With administrative and financial autonomy, ISM serves as the nodal agency responsible for shaping and executing the country’s long-term vision for semiconductor manufacturing, as well as fostering a chip design ecosystem.

The following year, Prime Minister Narendra Modi launched the Semicon India Programme, committing more than $10 billion as incentives to companies establishing fabrication units, display fabs, and facilities for assembling, testing and packaging chips.

“SCL was upgraded to 180nm technology, which we got in collaboration with Tower Semiconductor of Israel. It did not produce any latest technology but served its purpose in a big way by catering to our strategic sectors,” V.K. Saraswat, NITI Aayog member and member of ISM’s advisory committee, told THE WEEK.

According to Saraswat, the government realised that things had to be done in a different manner. “The journey from 180nm technology to ISM began sometime in 2012,” he said. “We decided to modify policies for ISM to give a greater push for the creation of a semiconductor ecosystem in India.”

As part of ISM, five groundbreaking semiconductor projects are now underway―four in Gujarat and one in Assam. Leading the mission is the PSMC-Tata Electronics facility in Dholera, which is expected to have a monthly output capacity of 50,000 wafers―a slice of semiconductor material, typically silicon, for fabricating chips. PSMC will transfer advanced technology to manufacture a range of chips―28nm, 40nm, 55nm, 90nm and 110nm―that will cater to the surging demand across sectors such as automotive, computing, data storage, wireless communication and artificial intelligence.

“The Gujarat government also plans to develop a Semicon City, which will serve as a vibrant hub for the semiconductor ecosystem in India,” said Manish Gurwani, who served as director, Gujarat State Electronics Mission.

In 2022, Gujarat became one of the first states to introduce a dedicated semiconductor policy that charted an ambitious five-year plan to attract global players. The policy offers a range of incentives, including up to 40 per cent capital expenditure assistance for fab projects, full reimbursement of stamp duty and registration fees, and subsidy on land required for a fab up to certain area. Companies are provided access to high-quality water at Rs12 per cubic metre for five years, along with a power tariff subsidy of Rs2 per unit for a decade.

According to Gurwani, Gujarat’s semiconductor policy is well-aligned with ISM. “No separate scrutiny is required for projects approved by ISM, reducing the timeline for state approval and additional burden for the investor,” said Gurwani. The Dholera fab, he said, was approved by the state government within 24 hours of the ISM clearing it.

The incentives are already yielding results. Apart from the Dholera fab, CG Power and Industrial Solutions―partnering with Renesas Electronics Corp of Japan and Stars Microelectronics of Thailand―is developing an OSAT (outsourced semiconductor assembly and test) facility in Sanand with an investment of Rs7,000 crore. Micron is setting up an ATMP (assembly, testing, marking and packaging) facility in Sanand with a Rs22,516 crore capital investment, supported by a pilot project site already in operation. Kaynes Semicon Pvt Ltd is investing Rs3,300 crore to establish another ATMP unit there.

These plants are being established under the second phase of the Sanand Industrial Estate, developed by the Gujarat Industrial Development Corporation. The first phase, spanning 2,056 hectares, hosts more than 500 global companies, including top auto manufacturers. A key centre for auto ancillary, pharmaceuticals and electronics industries, Sanand is evolving into a major research and development hub.

“They (the state government) have given us a dedicated, 24x7 power and water supply, which is what a semiconductor project needs. What we also need is an ecosystem, and that’s why the government has ensured multiple projects in this region,” said Wasi Uddin of Kaynes. Once fully operational, the Kaynes facility, spread across 1.84 lakh square metres, is expected to produce 2.3 billion chips annually.

To help establish a semiconductor and packaging ecosystem, the state government organised the Gujarat SemiConnect in March, bringing together 1,500 global delegates, 250 exhibitors, and a number of industry leaders. Six country-specific roundtables and seven panel discussions were held during the event, reinforcing Gujarat’s growing presence on the global semiconductor map.

Assam is another state that has benefited from India’s renewed semiconductor push. Tata Electronics is building a state-of-the-art assembly and test facility in Jagiroad in Morigaon district with an investment outlay of Rs27,000 crore. The facility will focus on three platform technologies―wire bond, flip chip and integrated systems packaging―that have crucial applications in sectors such as automobiles, communications and network infrastructure.

Assam Chief Minister Himanta Biswa Sarma said the Jagiroad project would transform the state’s economy. Unlike Sanand, an established industrial hub where the Gujarat government is enhancing existing infrastructure, Jagiroad starts from scratch. As part of the state’s most underdeveloped regions, Jagiroad lacks the essential framework for large and medium-scale industries. The Tata facility is expected to be a beacon of economic transformation.

“This facility will initially create 27,000 jobs, with numbers set to grow over time,” Industries and Commerce Minister Bimal Borah said at the Assam Semiconductor Conclave in Guwahati last December. He projected Assam’s proximity to southeast Asia as a strategic advantage, saying the government was in talks to host representatives from ASEAN countries. “The Jagiroad project belongs to the entire northeast, and it will be a gateway for the region’s industrial development,” said Borah.

Tata wants to help build an entire semiconductor ecosystem around its Jagiroad facility. “We will engage with the ecosystem and the entire chain. Suppliers of equipment, raw materials and gases will have to work as a team,” said Srinivas Satya, president (components business and supply chain), Tata Electronics.

Confident that the projects in Gujarat and Assam are progressing well, the Union government is gearing up for phase two of ISM. With a proposed $15 billion outlay, said Union Minister of Electronics and IT Ashwini Vaishnaw, phase two of ISM aims to expand beyond chip manufacturing, offering strategic support for raw materials, equipment, gases and specialty chemicals―key components essential to semiconductor production.

Also Read

- Huge ‘Atmanirbhar Bharat’ move! India greenlights four new semiconductor plants

- Chip giants meet: What is brewing between Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang and TSMC CEO C.C. Wei?

- India to get sixth major semiconductor plant; HCL-Foxconn unit to add 2,000 jobs

- 'Everyone says China Plus One; the One should be India': V.K. Saraswat

- Why no country can be 'aatmanirbhar' in semiconductor sector

- India is making strides, but reliance on imports will not diminish overnight

India’s chip ambitions extend beyond commercial manufacturing. A significant milestone has been the Union government’s initiative to revamp SCL’s Mohali facility. As part of a major upgrade, India’s first fab is set to double its manufacturing capacity, with modern tools being introduced to enhance production efficiency. The government is also spearheading a Rs2,000-crore effort to augment SCL’s chip production capabilities to 65nm, 40nm and 28nm nodes.

Also, India has signed an agreement with the US to establish a semiconductor fab dedicated to national security―a first of its kind that will focus on advanced sensing, communication and power electronics for national security.

A unique advantage that India has in the semiconductor space is that 20 per cent of the global chip designing workforce is based in the country. In recent decades, major players such as Intel, NXP and Qualcomm have set up expansive global capability centres in cities such as Bengaluru, Hyderabad, Noida, Pune and Chennai.

“Initially, India’s appeal to global semiconductor companies was largely driven by cost advantages. However, over the past decade or more, that narrative has significantly evolved,” said Ashish Lachhwani, a former Qualcomm engineer who is preparing to launch a startup. “It’s not just about affordability anymore. It’s about the knowledge base and expertise built over the years―they have positioned Indian engineers to design and define next-generation semiconductor products.”