On March 12, members of the dalit community in Gidhagram, West Bengal, entered the Gidheshwar Shiv temple, breaking a longstanding caste barrier. These dalit families, traditionally cobblers and weavers, were denied entry to the temple during the Maha Shivratri celebrations, exposing the illusion of a modern and egalitarian state. They were finally able to visit the temple, but only under police protection.

This incident is far from isolated. Caste discrimination and the practice of untouchability continue to plague India. Although 75 years have passed since untouchability was abolished under Article 17 of the Constitution, dalits, also known as scheduled castes (SC), continue to be excluded from public spaces, including crematoriums. While local authorities in Gidhagram intervened to protect the constitutional rights of the marginalised, the persistence of such practices highlighted the failure of systemic reform.

In September 2024, a 30-metre ‘untouchability wall’ constructed by caste Hindus in Vishwanatham village in Tamil Nadu’s Virudhunagar district, to conceal the cremation ground used by dalits, was demolished by panchayat authorities. In Karnataka’s Yadgir district, the midday meal programme at a government school was disrupted after the cook and his assistant refused to wash the plates used by dalit children. In another incident, a government school headmistress, Nirmala Dange, in the same district received death threats after inviting a dalit as the chief guest for Republic Day celebrations.

Elsewhere, a dalit groom was targeted by upper caste Thakurs in Madhya Pradesh’s Damoh district for using a horse-drawn carriage during his wedding procession. Three people who helped pull the carriage―Rahul Rajak, Krishna Rajak and Jagdish Ahirwar―were beaten up. In Rajasthan’s Dev Doongri village in Rajsamand district, upper caste Rawats disrupted the funeral of a dalit man from the Salvi community, claiming the government-allocated burial ground was too close to their land. The funeral proceeded under police supervision. Dalits in Kadanur village in Bengaluru Rural district were denied haircuts at a barber shop, while in Mysuru’s Hallare village, another barber, Mallikarjun Shetty, faced a social boycott for offering his services to a dalit man.

In Tamil Nadu’s deep south, especially Tirunelveli, Thoothukudi and Tenkasi districts, there is a practice of students wearing coloured wristbands or threads to signify their caste. Thevars don red and yellow, Nadars wear blue and yellow and Yadavs sport saffron. Although they come under the Most Backward Community category, these communities are socially and politically powerful in south Tamil Nadu. Dalit Pallars, meanwhile, wear green and red threads and Arundhathiyars, the most oppressed, use green, black and white threads. Rings and bindis are also used for this purpose.

Justice K. Chandru, who was appointed by the Tamil Nadu government as a one-person commission to suggest how caste discrimination could be prevented in schools, said in his report that the threads worn by students were “coded markers of caste identity” and called for a ban. The report revealed that between May 2021 and April 2022, as many as 117 cases relating to disputes involving students were registered in Tamil Nadu. Of these, 24 cases were either due to caste identification or altercation due to intercaste love affairs.

Caste differences prevail in schools in other districts in southern and western Tamil Nadu as well. In some of the schools, attendance registers have caste columns and teachers call their students by caste names. “The school is only an extension of what is happening in society. Parents say they won’t send their children to school and take midday meal if the teachers are dalits,” Justice Chandru told THE WEEK. His recommendations are yet to be implemented.

An untouchability-free India is enshrined in Article 17 of the Constitution. Yet, caste discrimination persists, not as a remnant, but as an institutionalised feature of the so-called modern state. The nature of caste discrimination has evolved from overt to subtle, cloaked in hypocrisy and denial. According to dalit activists, untouchability has spread from villages to cities, infiltrating educational institutions, temples, barber shops, courtrooms, police stations, factories, government offices, corporate boardrooms and even political party offices.

“We often understand caste discrimination through brutal cases of caste atrocities, which represent overt discrimination. If you examine where dalits working in cities live and how they live, you will realise nothing has changed. Most dalits are still employed in cleaning or low-tier jobs. They continue to reside in ghettos lacking basic amenities,” said Rahul Sonpimple, president of the All India Independent Scheduled Castes Association, a grassroots organisation uniting dalit leaders and movements. The “untouchable” castes within the SC communities continue to perform menial tasks such as manual scavenging, grave digging, cremation and sweeping. They are ostracised, denied equal opportunities and forced into inhumane practices like bonded labour and the devadasi system (sex slavery).

“Untouchability is prevalent in rural India. Upper caste landholding communities prevent dalit families from migrating to cities, as this would deprive them of cheap labour and menial cleaning work,” said Bengaluru-based dalit activist Ruth Manorama. “In urban areas, dalit women are impoverished and live under the constant threat of eviction, owning neither homes nor land. Working in the unorganised sector with low-paying jobs, they cannot afford to send their children to school. Most are burdened by debt.”

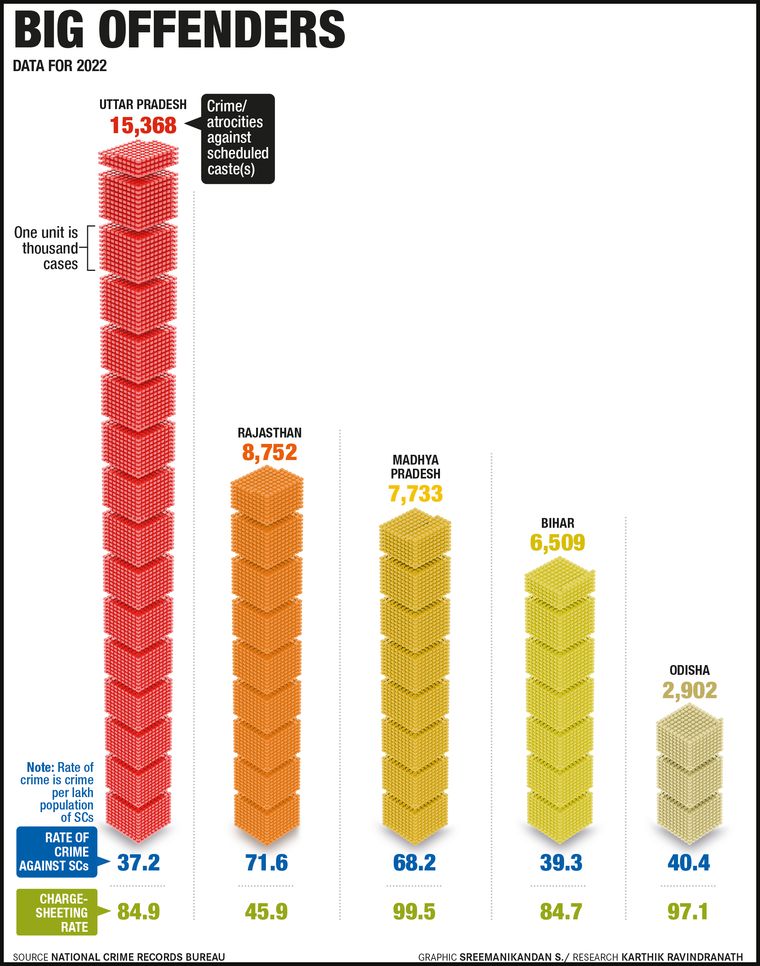

The Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe (Prevention of Atrocities) Act, 1989, was intended to end caste-based violence and discrimination. However, statistics paint a different picture. In 2022, the number of cases registered under the law for SCs were 57,582, and 10,064 for STs. While states such as Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Bihar and Madhya Pradesh lead the list, ‘progressive’ states such as Maharashtra and Karnataka fare no better. The conviction rate dropped to 32.4 per cent in 2022 from 39.2 per cent in 2020.

Only five states―Bihar, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Kerala and Madhya Pradesh―have established special police stations (Karnataka recently approved the creation of 33 special police stations and the recruitment of 450 personnel to handle emergency caste atrocity cases). Just 194 of 498 districts across 14 states have set up special courts to expedite trials.

Advocate Hariram A., a dalit activist associated with the Bahujan Samaj Party, said, “Courts and police often cite misuse of the Atrocities Act. The conviction rate is a mere 3–4 per cent. Most cases result in acquittals due to lack of evidence, as prejudiced or corrupt police fail to present it in court. Worse still, victims are pressured to compromise and withdraw cases. A casteist judge or police officer is the most dangerous, ensuring justice is never served. Some officers even encourage the accused to file counter-complaints against victims.”

Y. Mariswamy of the Samajik Parivartan Janandolan said convictions were low because police failed to gather and present evidence against perpetrators of caste-based violence, instead “advising” victims to settle out of court. “A dalit boy in love with a girl from a backward-class community was stripped and beaten by the girl’s parents in Bengaluru. Yet, the police neither arrested the culprits nor included serious charges,” said Mariswamy. “The Right to Education Act has failed its purpose, as no private school adheres to the requirement of reserving 25 per cent of seats for children from marginalised communities. The private lobby and politician-owned educational institutions are to blame for the Act’s failure. Sadly, government schools catering to SC, ST, and poor OBC children are neglected, lacking teachers.”

Shivam Sonkar, a dalit student, was denied admission by Banaras Hindu University to its PhD programme despite securing second place in the entrance exam in the general quota. Of seven available seats at the Malviya Centre for Peace Research, only four were filled. The university claimed that reserved seats remained vacant due to a lack of suitable applicants and that Sonkar, having qualified in the general category, could not be admitted under reserved criteria. Ajay Rai, president of the Uttar Pradesh Congress, said it was shameful, particularly as it happened in Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s constituency. Ashutosh Sinha, a Samajwadi Party MLC, has written to Modi, highlighting the incident as an obstacle to higher education for dalit students.

Hariram asserted that dalits needed political power, social capital and representation in high positions. Dalit intellectuals have started looking more at political empowerment. Sonpimple said the dalit question had historically remained just a caste issue. “If Gandhi’s caste reform was through social and spiritual means, Ambedkar’s idea of addressing caste discrimination was through political power. The dalit rights’ movement has passed through several phases.”

During the colonial era, dalit mobilisation in states like Tamil Nadu, Maharashtra and Punjab challenged the state, introducing a new concept of rights. Ambedkar’s Kalaram Temple Satyagraha (1930) in Nashik demanded equal access for dalits, pushing Hindu society to reflect on exclusion. “Babasaheb identified education as a tool for liberation, while political power and economic upliftment were essential,” said Sonpimple. “He advocated for a separate electorate for dalits but had to compromise under the Poona Pact of 1932, signed between caste Hindus and the depressed classes, which fixed reserved seats at 147 in the provincial legislatures.”

Today, 84 of 543 Lok Sabha seats are reserved for dalits, but they rarely exceed one-third of the voters. Consequently, dalit MPs must appeal to upper caste voters to win and cannot focus exclusively on their community. “While dalits have reserved seats, their political representation lacks power due to upper caste dominance,” said Hariram. Elected dalits prioritise parties over community, even amid crimes against them. Unsurprisingly, in 78 years of independence, there has been no dalit prime minister, only three presidents and seven chief ministers. Of 71 ministers in the Modi 3.0 cabinet, there are only 10 dalits. “The populism of successive governments has most affected the marginalised communities,” said Hariram. “Budgetary allocations exist only on paper; they are never spent and are returned to the treasury.”

He also pointed out that our executive and judiciary were dominated by upper caste officers. “Appointments and promotions hinge on nepotism. Even if a dalit reaches these positions through merit and hard work, they cannot escape casteist slurs or discrimination through denied promotions,” said Hariram. IAS or IPS officers, too, are unable to escape discrimination, said Manorama.

In urban areas, untouchability manifests subtly. Dalits are often refused rental housing. “Though landlords may not directly ask about caste, they probe thoroughly to uncover it. Displaying Dr Ambedkar’s portrait risks eviction or discrimination from neighbours,” said Mariswamy. Consequently, dalits are forced into ghettos lacking civic amenities. A stark example of modern untouchability can be found in the Anandapura slum in central Bengaluru, where dalit homes are denied piped water.

On March 14, Selvi, a widow and mother of four, was electrocuted while attempting to switch on a water pump. Residents have installed 30 pumps to illegally draw water from a pipeline supplying a local temple. “Our families have lived here for four decades without a water connection. Each pump serves four houses,” confided Rani (name changed), a resident, noting that Selvi was the fourth casualty. “A majority of us are educated today, but it does not ensure equality. Our locality is neglected by authorities. We are poor yet educated, working in garment factories, schools and offices, but we feel invisible,” she said.

Rani’s disillusionment echoes Dr Ambedkar’s, who converted to Buddhism in 1956 after feeling disenchanted with Hindu reform movements. He urged dalits to follow suit to escape caste oppression. He called for dismantling the “rigid and exploitative” caste system, which enforced inequality and subjugation. Criticising Hindu scriptures and practices for legitimising caste, he argued that no reform was possible while the system endured. He viewed untouchability as a direct consequence of the caste system, dehumanising millions of dalits by denying them basic rights, dignity and opportunity.

While Article 15 prohibits discrimination, Article 14 guarantees equality and Article 21 ensures the right to life and dignity by banning untouchability, the ‘invisible’ people―manual scavengers, grave diggers, cremators and ‘safai karmacharis’ engaged in sweeping and cleaning―bear the brunt. “I was born into a caste where everyone did manual scavenging. As a child, seeing someone pick up human excreta shocked me. I wondered how it was possible,” said Bezwada Wilson, national convener of Safai Karmachari Andolan (SKA). “But a casteist mind normalises it, wired to think that a dalit is born to clean, needing only to wash their hands or wear gloves. These gloves mask the inhumanity and hypocrisy of civil society.”

Two years ago, women sanitation workers from 10 states, including Delhi, gathered at Jantar Mantar in New Delhi, burning bamboo baskets used to collect excreta from dry latrines in a symbolic protest. Outraged by the government’s “white lies” about sewer-septic tank deaths, they demanded action. While the government reported nine deaths in 2022–23, the SKA recorded 339 based on news reports, FIRs and postmortem examinations.

Despite constitutional safeguards, systemic neglect, bureaucratic apathy and dangerous denial persist. A manual scavenger is defined as someone employed to clean, carry, dispose of or handle human excreta from an “insanitary latrine, open drain, pit”, railway tracks or other premises. Banned under the Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act (PEMSRA), the practice continues, disguised as “hazardous cleaning” due to loopholes in the amended 2013 law. The Act defines “hazardous cleaning” as manually cleaning a sewer or septic tank without employer-provided gear and excludes workers using “protective gear” (any one of the 44 types notified by the government) from being classified as manual scavengers.

“As per the Act, anyone employing a person for manual scavenging work, whether directly or indirectly, could be jailed for up to a year or fined Rs50,000, or both. For repeat offences, imprisonment could extend to two years or a fine of up to Rs1 lakh, or both. But there has not been a single conviction,” said Wilson.

The Centre claims that manual scavenging is not a caste-based occupation. However, a profile report by the ministry of social justice, as part of its National Action for Mechanised Sanitation Ecosystem (NAMASTE) programme, stated that nearly 92 per cent of sewer and septic tank workers belong to SC, ST and OBC (Other Backward Class) communities.

“How can the government make such a claim? Our groundwork clearly shows that the majority of manual scavenging workers are dalits and it is a caste-based occupation,” said Wilson. “There is no reconciliation, only denial, that caste discrimination exists. This is dangerous and unchecked within the system, including among IAS officers, the judiciary, and politicians. The prime minister turned cleaning into a spiritual experience. You see nothing wrong when you watch it from a place of privilege. Is sweeping the same as cleaning human excreta?”

On October 2, 2014, Modi launched the Swachh Bharat Mission, a national campaign to promote cleanliness and eradicate open defecation. “It created more chaos. More manual scavengers and sewage workers will be employed without new technology. There will be more manhole deaths, but they will not be registered. Sanitation workers, who deserve dignity and mechanisation of their work, will be garlanded and hailed as ‘soldiers’ and ‘martyrs’. Political leaders prefer photo-ops over structural reform,” said Wilson, adding that allocations for rehabilitation loans were nearing zero.

Social Justice and Empowerment Minister Ramdas Athawale told Parliament last year that of 766 districts, 249 declared themselves manual scavenging-free and uploaded certification on the designated portal. The rehabilitation package includes a one-time cash assistance of Rs40,000 and a back-end capital subsidy of up to Rs3.25 lakh. Dependents of manual scavengers are also eligible for self-employment projects worth up to Rs10 lakh (Rs15 lakh for sanitation projects) and skill development training for up to two years, with a monthly stipend of RRs3,000. “In our modern cities, we still believe in a sanitation model that involves human labour. It is a design flaw. It is time to detach caste from the design of the sanitation model,” said Wilson.

The devadasi system is another exploitative practice harming dalit communities. When Seetavva Dundappa Jodatti was honoured with the Padma Shri in 2018, it drew national attention to the controversial system, which was legally abolished in Karnataka in 1982, followed by similar bans in other states. In Karnataka, young girls from the “Maadiga” (dalit) community are dedicated to a deity in the belief that it would cure illness or bring good fortune to the family. Often, it leads to sexual exploitation by upper caste men.

Seetavva, the youngest of six daughters, was herself dedicated as a devadasi. She later escaped the system and founded MASS, an NGO dedicated to the rehabilitation of devadasis, through which she has rescued over 4,000 women. A 2018 study by Karnataka State Women’s University estimated that the state still has around 80,000 devadasis. Despite legal prohibitions, girls from marginalised communities continue to be forced into sex work under the guise of tradition. This led the National Human Rights Commission to demand a report from the Centre on the “continuing menace” of the devadasi system in six states―Karnataka, Kerala, Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Telangana and Maharashtra.

“I have been working for the last 27 years for the rehabilitation of former devadasis in Belagavi, and there are no more cases here. But I notice young women being forced into this in other districts. The government must curb the practice through stricter implementation of the law. Unless these women achieve economic independence, they will continue to be exploited,” said Seetavva. She has urged the Karnataka government to enhance pensions to Rs5,000 a month and grant two acres to each beneficiary.

Grave digging, too, is a caste-based and hereditary occupation in many parts of the country. The irony is stark in villages, where dalits, being landless, must endure humiliation even in death. They must scout for burial land, as upper caste communities deem it inauspicious to witness a dalit funeral and often respond with social ostracism or violent attacks. Souri Raju, a fifth-generation grave digger who lives with his wife and six children inside the Kalpalli crematorium premises in Bengaluru, said it was a long battle to secure even minimum wages.

“Bengaluru has 50 burial grounds and 12 electric crematoriums. Workers here are paid Rs13,000 a month. Our members employed by city corporations might get wages, but those in rural areas survive on the charity of grieving families,” said Raju, state secretary of the graveyard workers’ association in Karnataka. “We trust only God and people’s goodwill and continue doing what we do. We grew up eating rice sprinkled on cemeteries and have come to realise that we carry nothing with us when we leave this world.”

―With Lakshmi Subramanian and Puja Awasthi

Blocked toilet

By Puja Awasthi

Pushpa Gautam, an administrative officer at Bundelkhand University, has long been fighting a battle against authorities for the most basic human rights―clean drinking water and access to a toilet. Gautam’s female peers have been given office chambers with toilets and official residence as per their seniority. When the 45-year-old complained on the university’s WhatsApp group, she was accused of maligning its image.

Things came to a head in 2018, when at a meeting of the university’s employees’ union and the administration, Gautam was slapped and had a chair thrown at her. She was being accused of harassing her peon (an OBC), who had refused to get her water or tea on one pretext or the other. She was also told that she was misusing her status as a woman, as a dalit and as a disabled person (she had polio as a child) to garner sympathy.

An undeterred Gautam filed a police case against six people who had attacked her and, though an administrative inquiry led to the removal of the six, her case is still pending in court. Kuldeep Kumar Baudh, the lawyer representing Gautam in court, said that it was not enough that justice be done, but that it be dispensed in a manner that ensured the dignity of the most vulnerable.

Manholes and loopholes

By Prathima Nandakumar

Manual scavenging is banned, but exists in practice. On March 16, Panth Lal Chander, 43, climbed down a clogged manhole in Delhi to help his brother Ramkishan and another relative Shiv Das, who had fallen unconscious. He inhaled toxic gas and fainted. His 10-year-old son, who was watching the trio, screamed for help and a fire department team rushed to the spot to pull out the migrant workers from Chhattisgarh. While Panth died of asphyxiation, the other two survived. None of them was wearing protective gear.

The police registered a case under Section 105 (culpable homicide not amounting to murder) of the Bharatiya Nyaya Sanhita and Sections 7 and 9 of the Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013.

The Delhi Jal Board said these were not department staff nor were they contract workers. All three workers, part of the SC community, had been hired by a private contractor. As these men are among the lakhs of “invisible” workers in the informal sector, and are not documented as workers, their families are left in the lurch. Panth leaves behind a wife, four daughters and a son.

In a reply in the Rajya Sabha, the Modi government said there were 294 sewer-related deaths in the past five years across the country and 249 victims were compensated.

Honour and horror

By Rahul Devulapalli

On March 10, the Telangana High Court gave its verdict in a sensational 2018 case. Pranay, a dalit, married Amrutha, from a dominant caste, against her family’s wishes. They got married in Arya Samaj in Hyderabad and sought police protection. Months later, Pranay was leaving hospital with his pregnant wife when an unknown man hacked him to death with a machete. The court sentenced the contract killer―hired by Amrutha’s father―to death. Her father died by suicide in 2020.

“Initially, the public sympathised with the couple. But, after the suicide, some people started seeing him as a father who simply loved his daughter,” said A.V. Ranganath, the IPS officer who investigated the case.

Even the police uniform doesn’t guarantee escape from such violence. K. Nagamani, a woman constable attached to the Hayathnagar police station in Hyderabad, was riding her two-wheeler to work last December when a car hit her from behind. Her brother, Parmesh, got out of the car and stabbed her to death. Her only ‘mistake’―she married a dalit.

Parmesh, who is from the backward class community, surrendered and confessed that he was enraged that Nagamani divorced her first husband to marry B. Srikanth. “He warned us beforehand that he will kill us and he did it without any fear,” said Srikanth. “He is now out on bail. How can couples planning inter-caste marriages feel safe if such people are not punished immediately?”

Price of pride

By Lakshmi Subramanian

Last month, S. Yuvaraj, convicted in the high-profile murder of Dalit youth V. Gokulraj, was released on parole to attend a family function. He received a grand welcome in his home town Namakkal, with social media pages linked to the Gounder community―a dominant intermediate caste in western Tamil Nadu―celebrating him as their “pride”. Yuvaraj, founder of the caste outfit Theeran Chinnamalai Gounder Peravai, had evaded arrest for over 100 days in 2015 after police began investigating Gokulraj’s murder.

According to the police, Gokulraj, a 21-year-old engineering graduate, was abducted by Yuvaraj and his associates for speaking with his classmate Swathi, who belonged to the Gounder community. A day later, his decapitated body was found on railway tracks near Erode. Yuvaraj was eventually arrested and convicted of the murder. In 2023, the Madras High Court upheld his conviction. Gokulraj’s family had spent nearly a decade seeking justice. “We have lived in fear for 10 years,” said his brother S. Kalaiselvan. “Yuvaraj’s welcome sends a disturbing message―that caste groups will continue to support people like him. It makes us feel even more unsafe.”

Wedding crashers

By Prathima Nandakumar

Mukesh Parecha took no chances. The 33-year-old lawyer wanted to reach his wedding location on a horse, but because the dominant castes in his village did not take kindly to a dalit man doing so, he requested police protection. On February 6, a team of 145 policemen arrived in Gadalvada village of Gujarat’s Banaskantha district to escort the groom. The wedding was incident free; the local police inspector and Vadgam MLA Jignesh Mevani accompanied the procession in a car.

Parecha’s fears were not unfounded. A groom riding a horse is a symbol of pride and domination in several north Indian states. A dalit man doing so is seen as a challenge to established caste hierarchy.

There have been numerous cases of dalit grooms being attacked for their “arrogance”. Last May, four men beat up and forcibly pulled down Naresh Jatav from the horse carriage at Rithodan village in Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh. The accused are said to have objected to the procession passing by their house and allegedly threw water and casteist slurs at the groom’s relatives. They also fired gunshots in the air before beating the wedding party with sticks and breaking the DJ equipment and the canopy of the carriage.

An FIR was filed at the Karahiya police station against four members of the Rawat family. A counter-complaint was lodged by the women of the Rawat family, alleging misbehaviour by the groom’s relatives.

Parecha, being a lawyer, anticipated the violence and potentially dodged a bullet. Most others don’t.

Power failure

Even powerful dalit politicians remain vulnerable to caste discrimination. Political power and legal protections often fail to dismantle centuries-old prejudices, leaving even prominent figures grappling with discrimination. On April 7, senior BJP leader and former three-time MLA Gyan Dev Ahuja from Rajasthan allegedly sprinkled Ganga water in a temple in Alwar district, a day after the visit of Tika Ram Jully, Rajasthan’s first dalit leader of opposition. The opposition Congress alleged that Ahuja was trying to cleanse the temple following Jully’s presence during its consecration on Ram Navami on April 6. After facing significant criticism and being labelled an “anti-dalit party”, the BJP swiftly suspended Ahuja from its primary membership.

Earlier this year, CPI(ML) legislator Gopal Ravidas from Bihar filed a complaint claiming that local people barred him from inaugurating a government school building because he was a dalit. The incident occurred on Republic Day, within the Parsa Bazar police station area in Patna district. Following his complaint, police registered an FIR, applying sections of the Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes (Prevention of Atrocities) Act. Ravidas alleged that villagers even stopped him from attending the flag-hoisting event on Republic Day.