It is 8am

at Delhi’s ITO barrage. The early summer sun isn’t too hot, the ailing Yamuna looks calm, rather domesticated and subdued. Decked up in Kashmiri pheran, and docked up on a boat, a young soon-to-be-wed couple poses for the pre-wedding shoot, capturing the wide expanse of the river.

Just a little over 200km southeast, the river lay testimony to another love story, of Shah Jahan and Mumtaz that birthed the most extravagant symbol of love―the Taj Mahal. Legend has it that the Mughal emperor intended to build a black Taj Mahal as his own mausoleum, opposite the white one. Agra also boasts a red Taj Mahal, built not by a man but a woman in memory of her husband John Hessing, a Dutch traveller-turned-army officer for the Marathas in Agra in the 1790s.

And right between Delhi and Agra, the river is said to have witnessed the love story of Radha and Krishna, and their divine dance of love, or Raasleela, in Vrindavan.

A river of dark love, Yamuna is celebrated in both myth and history. It is associated with the pranks of the dark god Krishna, and his dance on the dark snake Kaliya who was poisoning its very waters. It is also associated with the secret, unrequited love of Salim and Anarkali, and the several ancient and medieval monuments that dot its banks.

“Without the Yamuna, there is no Mathura or the tales of Krishna,” says a priest at one of the ghats of this ancient temple town―the supposed birthplace of the Hindu god―that lies on the banks of this holy river. “Manus ho to wahi Raskhani baso Braj Gokul gaon ke gvaran / Jo pasu hon to kaha bas mero charaun nit Nand ko dhenu manjharan (If I, Raskhan, am reborn as a human, I wish to be a cowherd in the village of Gokul in Brajbhumi. If born an animal, I would like to be a cow in the herd of Nanda, grazing blissfully all day),” wrote 16th century Sufi poet Raskhan. How a Syed Ibrahim Khan became the Krishna bhakt (devotee) Raskhan is for the scholars to decipher, but his grave still rests in Gokul on the banks of Yamuna, bearing testimony to India’s Ganga-Jamuna tehzeeb (composite culture).

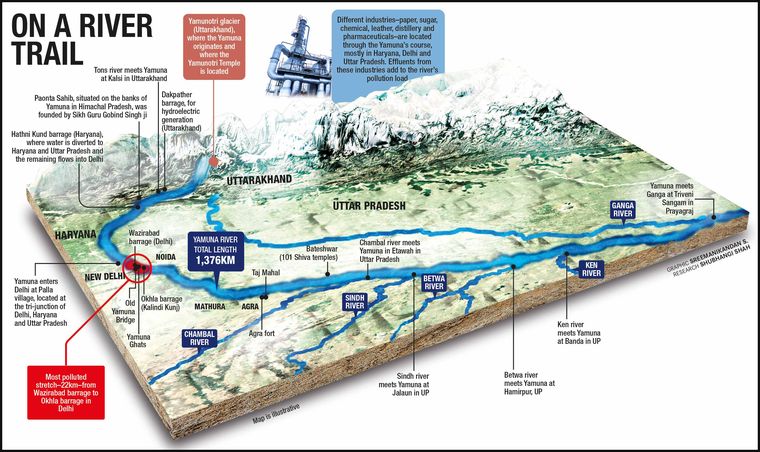

Several stretches upstream, at a height of 6,387m, the river rests as a symbol of deep devotion for the Hindus at Yamunotri, its origin, in Uttarakhand. Lakhs of devotees, old and young, embark on this trek to worship the river goddess at the Yamunotri temple, one of the Char Dhams (Hindu pilgrimage sites). The river tumbles down the mountain slopes with force, vibrant with pristine blue waters. Travelling 1,376km through varied landscapes, four states and Delhi, it meets the Ganga at the Triveni Sangam (the site for the Kumbh Mela) in Prayagraj, its character starkly different downstream―it is wider, calmer and darker. And through its course, it flows through major towns and cities, having birthed several big and small empires, the remains of which stay mute on its banks, and it continues to host the seat of political power in India.

Despite the tales, myths and grandeur, Yamuna is now often synonymous with pollution and filth. A simple Google search will first reveal pictures of a frothy Yamuna in Delhi and not the crystal clear water it holds in its upper reaches in Uttarakhand. Also known as Kali Nadi (dark river) or Kalindi, in reference to Goddess Kali, its current state reflects the very colour it is named after owing to decades of pollution.

And here, it also imbibes a political colour.

Politics over Yamuna ‘ma’

On the bank of the river, at the stunningly colourful ghats in Mathura, a priest is carrying out a ritual in which the Yamuna is adorned with saris. Stacks of saris can be seen on the bank, along with flowers in plastic bags, burnt incense sticks and broken idols. On being asked if all this wouldn’t pollute the river, he points fingers at Delhi. “It is all coming from there,” he says.

Not entirely inaccurate as reports suggest that the 22km stretch of the Yamuna that flows through urban Delhi, from Wazirabad to Okhla barrage, makes for a mere 2 per cent of its length but contributes to over 75 per cent of its pollution load.

The issue of Yamuna cleaning has also opened a political front since the assembly elections in Delhi in February, campaigning for which AAP supremo and former Delhi chief minister Arvind Kejriwal blamed neighbouring Haryana for “poisoning” the river. Kejriwal lost to BJP’s Parvesh Verma, Delhi’s new water minister. Even Prime Minister Narendra Modi raised the slogan: ‘Yamuna Maiya Ki Jai (Hail Mother Yamuna)’ and pledged to make the river the pride of Delhi post BJP’s win. And after being sworn in on February 20, Chief Minister Rekha Gupta, along with cabinet ministers, went to the recently-built Vasudev Ghat near Kashmiri Gate, and did Yamuna Aarti. If that was intended to show her government’s intent, it was optics 101. This came just a few days after Lt Governor Vinai Kumar Saxena announced a plan to clean Yamuna, Delhi’s lifeline, in three years.

A city’s lifeline

Standing on the banks of the heavily-polluted Yamuna near the Salimgarh Fort, built by Sher Shah Suri’s son Salim in 1546, less than a kilometre from the Red Fort, built by Shah Jahan, with the old iron bridge built by the British on one side, I wonder how the river would have looked then, prompting scores of rulers to base their capitals here.

“It was never the lifeline of Delhi, at least not before the 1880s when the British set up the first water pumping station at Chandrawal, making it a source of drinking water,” says heritage and conservation activist Sohail Hashmi. The river didn’t flow through any of the seven medieval capitals that came up, all situated on its west bank, with wells and stepwells being used for drinking water. In fact, Sultan Feroze Shah Tughlaq started constructing a canal to bring the river water from Hisar to Kotla Feroz Shah, which was later completed by Mughal Emperor Shah Jahan. It then started flowing through the Red Fort and Chandni Chowk, and was called Nahr-i-Bihisht, the stream of paradise.

But why was Tughlaq building a canal to get water from the Yamuna to Delhi?

“In my understanding, the river water wasn’t potable even then, probably because the Yamuna in Delhi flows on the bedrock of the Aravallis, which in Delhi is quartzite rock that has a lot of silica and mica in it. People then wouldn’t have known what these were but would have probably experienced that drinking it was causing several ailments. The Yamuna coming from Hisar, on the other hand, is carried on a thick layer of alluvial soil,” says Hashmi. Indeed, Tughlaq and the Mughals weren’t the first to command the Yamuna’s waters. Lore has it that Krishna’s brother Balram, the god of farmers, had dug a canal to divert a recalcitrant Yamuna’s waters to Vrindavan during a drought.

Strangely, the river’s decay in Delhi began when it became the source of drinking water with the setting up of the water pumping station after which piped water began to be supplied to Shahjahanabad. “And by the 1890s, the British also introduced the sewage system in Shahjahanabad, after which sewage began to flow into the Yamuna,” says Hashmi.

So, the water is pumped out from one side and sewage dumped into it on the other, what does it leave the river of?

Where river becomes a glorified drain

As the Yamuna enters the Yamunanagar district in Haryana to the Hathni Kund barrage, the river water is diverted to Haryana and Uttar Pradesh by the Western Yamuna Canal and Eastern Yamuna Canal, respectively. The remaining flows into Delhi, entering at Palla, a village located on the tri-junction of Haryana, Uttar Pradesh and Delhi.

The water, although not crystal clear, looks visibly in better health. A temple, dedicated to goddess Yamuna, can be seen on the river bank, bearing signs that read, ‘Ek snaan Yamuna maiyya ki swachhta ke naam [Take a dip for Yamuna’s cleanliness]’, and the more important ‘Kooda kachredaan mein daale [Throw waste in the dustbin].’

At Palla, the dissolved oxygen (DO), a marker of a river’s ability to support aquatic life, is 6―above the required threshold of over 5 milligram per litre (mg/l)―as per the latest report by the Delhi Pollution Control Board (DPCC) for February. And the faecal coliform, the level of sewage contamination, was 1,300 MPN (most probable number) per 100 ml, which is tolerable for bathing. The permissible limit is 2,500 MPN/100ml.

From Palla, it reaches Wazirabad, where it is barraged for Delhi’s source of drinking water. There is much activity here, with people worshipping and a group of divers taking turns diving into the river to recover coins. It is a productive day for 30-year-old Sagir, who not only recovers a huge pile of coins but also shows off his capability to remain underwater for over a minute. “On a good day, I can recover coins worth over Rs200,” he says. But doesn’t being in the dirty river water trigger health concerns? “Where’s the dirt?” he interjects. “You can even see the riverbed.”

The dissolved oxygen at Wazirabad was 5.3 in February, and the river appears visibly alive, with much activity and a calm and peaceful atmosphere.

But this changes less than a kilometre away. “It gets dirty over there,” says Ramlal, another diver, pointing at the Najafgarh drain. It is the biggest polluter, dumping as much as 70 per cent of the pollution load into the river. It does so near Signature Bridge, which Delhi boasts as a modern landmark and the AAP government promoted as a tourist destination. Interestingly, swanky cafes at Tibetan refugee settlement-turned-city’s hip locale Majnu ka Tila offer a view of the bridge and the river, the guests unknowing that it is exactly where the Yamuna’s water deteriorates sharply, making it more of a glorified drain.

At ISBT bridge, less than a kilometre downstream from the Najafgarh drain, the faecal coliform reaches a whopping 5.4 million MPN/100ml, and biochemical oxygen demand (BOD), reflective of a river’s ability to heal itself, is 46, much beyond the limit of 3mg/l.

Just 3km away is the newly constructed Vasudev Ghat. Spanning 145m between the Yamuna Ghat and the Nigambodh Ghat, it boasts manicured lawns, carved pavilions, seasonal flower, native and naturalised trees, and a giant topiary of ‘Maa Yamuna’. It was inaugurated by the lieutenant governor last year, and was where the new Delhi CM and her cabinet ministers performed Yamuna aarti after being sworn in.

A newly made staircase leads to the water, and people can be seen resting, taking selfies and making reels. The makeover is impressive, but something lingers. It is the stench, of the river.

But that doesn’t bother a trio making an Instagram reel. “The aesthetics here are nice,” they say. A couple can be seen walking hand-in-hand on the manicured lawn, the river bearing testimony to yet another love story. The stench doesn’t bother them either. ‘Has the river evaded consciousness of the people who inhabit the city, rendering its current state more of an inconvenience that can be ignored,’ I wonder.

According to Hindu scriptures, the Yamuna is considered the sister of Yama, the god of death. That makes it but an irony that the river that serves as the site of last rites is virtually dead in Delhi. A recent parliamentary committee report observed that the Yamuna in Delhi was “virtually non-existent” because of insufficient levels of dissolved oxygen, and called for an “urgent, lucid and coordinated response” from all stakeholders to improve the situation.

This abysmal state of the river is nowhere as evident as in Kalindi Kunj. A thick foam floats on the river water, the stench so bad that it is hard to stand even after covering the nose with a napkin. But what is even more shocking and jolts you into realisation is the surrounding, absolutely apocalyptic, with not a single soul to be seen nearby but only a couple of stray dogs fighting over a piece of meat. The weather feels grim, like during somebody’s death. Only in this case, it is the atmosphere generated by a river’s death.

At Okhla barrage, the river’s dissolved oxygen is nil and faecal coliform a staggering 9.2 lakh MPN /100 ml.

The issue fans out of Delhi, as the recent parliamentary committee report on the ‘Review of Upper Yamuna River Cleaning Project Up to Delhi and River Bed Management in Delhi’ noted that at 23 of 33 locations on the Yamuna (six in Haryana and Delhi each, and 11 in Uttar Pradesh), water wasn’t found fit for bathing. It also noted that there is no dissolved oxygen in around 40km stretch of the river in Delhi, except at Palla, and called for a study to be undertaken by the National Mission for Clean Ganga with the environment ministry to assess the damage rendered to the river, its ecology and aquatic life.

Where the problem lies

Pankaj Kumar, who goes by the name Earth Warrior on Instagram, has been carrying out clean-up drives along the Yamuna’s bank since 2019, with the recent one at Kalindi Kunj. “We do solid waste removal, such as of clothes, idols, plastics, etc. We segregate the green waste, leave them there, and the municipal corporation takes away the rest,” says Kumar, who adds that a tougher task is to sensitise people. “Throwing waste is one thing, but people also take bath in it, despite seeing the thick foam. We all have seen shocking visuals of devotees taking a dip in this water during Chhatt puja. We have even been sued for stopping people from doing so.”

Kumar encapsulates the state of the river in Delhi with a simple: “Ye nadi nahi ye, naala hai [This isn’t a river, but a drain].” Waste generated from worship forms a miniscule part of the problem, says Vibha Dhawan, director-general of The Energy and Resources Institute (TERI).

As many as 22 drains empty their load into the river, and as it leaves Delhi at Asgarpur in Delhi, the faecal coliform reaches a staggering 1.6 crore MPN/100 ml.

“Here, we need to look at the sewage treatment plants (STPs), if they are working at an adequate capacity. The answer is no,” says Dhawan.

Delhi generates 792 million gallons per day (MGD) of sewage of which only 550MGD is treated, as per reports. The remaining flows untreated into the Yamuna. As per the latest report by DPCC, 18 of 36 STPs in the city, which includes Okhla, Sonia Vihar and Ghitorni, failed to meet efficiency norms in February. “Where Yamuna enters Delhi in Palla, the faecal coliform is a little over 1,000 and where it leaves Delhi at Asgarpur, it is over 1 crore, which is reflective of the human and animal waste floating in the river, which means the sewage isn’t being treated properly,” says Kumar. At ITO barrage, where the faecal coliform is 43 lakh MPN/100ml, children can be seen playing in the river. “It is like welcoming a medical emergency. Here, the government, too, should take an initiative by just installing boards that the river water isn’t fit for bathing,” he says.

According to Dhawan, along with the treatment of sewage, the river’s flow is also a problem, which reduces significantly as it enters Delhi. The parliamentary committee report, too, noted that the key concern of maintaining an adequate environmental flow remains unaddressed. It observed that “there is almost nil environmental flow available at downstream of Wazirabad barrage during 9 out of 12 months in a year”.

Encroachment along the river, too, remains an issue with the National Green Tribunal having reprimanded the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) for failing to comply with its 2019 order on the removal of encroachments from the Yamuna floodplain. On the other hand, the DDA has said that it reclaimed 300 acres in an anti-encroachment drive conducted between August 2022 and January 2024.

“While there are regulations, if you visit these areas, you can see dhobi ghats, waste from which enters the river. Then, there is this huge industrial belt that adds heavy metals into the river,” says Dhawan.

River in political focus

In her maiden budget speech on March 25, the Delhi chief minister mentioned the Yamuna 17 times. Rapping the previous AAP government, she argued that it completely failed to clean the river. “Vows were taken to save Yamuna ji, but it was instead turned into a drain of filth,” Gupta said. Notably, Kejriwal, while campaigning during the 2020 Assembly elections, had vowed to clean the river and take a dip in it by February 2025. While he won, not much changed on ground.

“Delhi was once irrigated by the clean water of the Yamuna. But it is now struggling with a water crisis, overflowing sewage and polluted water reservoirs. The indifference of the previous governments meant the thirst of Delhi couldn’t be quenched. Indeed, the water crises only deepened,” Gupta said, as she announced Rs500 crore for the cleaning of Yamuna. Additional funds were announced for improving capability of STPs.

Also Read

- Delhi flood alert: Amid relief measures and MCD struggles, residents in tents as Yamuna swells

- In Agra, the Yamuna takes on many avatars

- River cruise on Yamuna will make Delhi more sustainable, tourist-friendly: Sarbananda Sonowal

- Yamuna needs comprehensive cleansing of sewage and stronger water flow: Jeevesh Gupta

- In Mathura, the Yamuna becomes a goddess, revered as one of Lord Krishna’s wives

“To clean Yamuna ji, we will build 40 decentralised sewage treatment plants, so that sewage is treated at the source itself. In addition, modern machinery will be purchased with an amount of Rs40 crore, among them modern devices like trash skimmer, weed harvester and dredgers,” the CM said. Another Rs200 crore was announced for the restoration of the Najafgarh drain, the primary polluter. As many as 32 real-time water quality monitoring stations, “equipped with advanced sensors that will constantly monitor the contamination level in the water,” will also be set up. “We are committed to making Delhi’s water management modern, scientific and sustainable,” said Gupta.

An ambitious roadmap, adding to which is a Memorandum of Understanding signed on March 11 by the Delhi government and the Inland Waterways Authority of India to run a water ferry service upstream of Wazirabad on a 4km stretch. Earlier in March, Water Minister Verma had emphasised the new government’s plans to promote tourism by introducing ferry and cruise service along the 8km stretch between Wazirabad and Sonia Vihar. Meanwhile, the LG, on February 16, announced the start of a cleanup drive, which included deploying trash skimmers, weed harvesters and dredging machines.

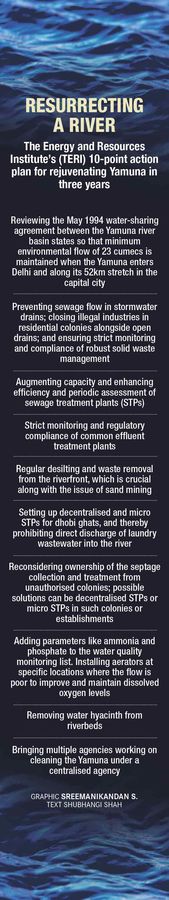

The Delhi government aims to clean the river within three years. Meanwhile, TERI, too, had shared a 10-point action plan to clean the river within the same time. “The solutions are everywhere,” says Dhawan.

But will the Yamuna be revived from a dark glorified drain to become the holy river that birthed many an empire will be crucial to see.