The crowds that thronged the sangam waterfront in Prayagraj have thinned down, and the tents and pontoon bridges, the cameras and the barricades have all been taken down. But the Mahakumbh will live on in the crores of videos and photos posted on social media, capturing every aspect―the personal and the political, the sacred and the profane, and the agony and the ecstasy―of an event billed as the ‘biggest gathering of humans in history’.

It was also undoubtedly the most youthful of all Kumbh Melas. By one estimate, more than half of the 66 crore or so who took a holy dip, as estimated by the Uttar Pradesh government, were below the age of 30. Another study, by the Govind Ballabh Pant Social Science Institute, also took note of the changing participation patterns, with growing number of women and a notable presence of those in the 18-35 age group.

Dheeraj Chauhan, 29, of Noida describes himself and his gang of friends as “not particularly religious or anything like that”. But that did not stop them from setting off on the long, crowded and chaotic train journey to Prayagraj, and taking a 4am ‘snan’ at sangam ghat. “We were a bunch of boys out on a trip, but the mood was certainly spiritual,” he says.

“Nothing is possible without belief,” says Akash Sharma, 22, a priest in Haridwar. “More than my upbringing, it is when I studied the scriptures and mantras further that I became a staunch believer.” Sharma comes from a family of priests, but his father had veered off the tradition by taking up a private sector job. But Sharma has decided to join the family profession. “I feel more satisfied and have more peace of mind in this line of work,” he says.

For an increasingly large number of young Indians, faith is giving solutions and solace in a fast-changing world. And they are taking to it with open arms, cutting across the religious, caste, creed and urban-rural divide.

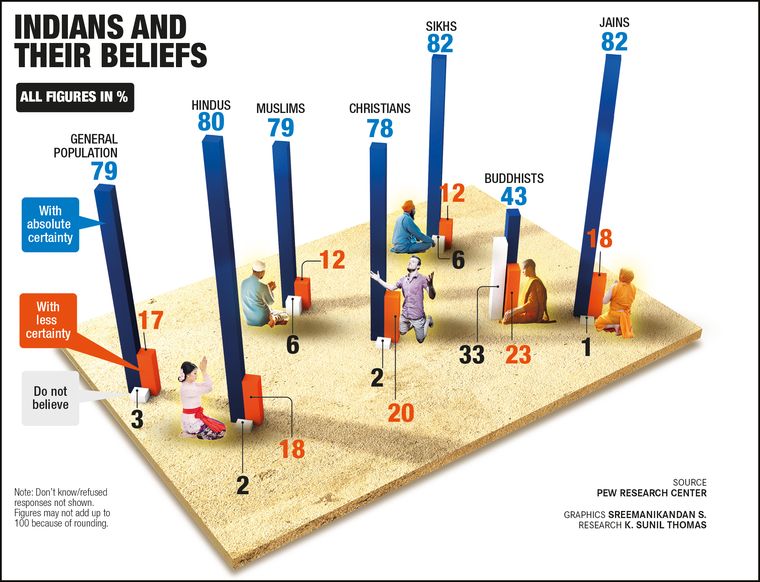

A recent study by Pew Research Centre had noted that as much as 97 per cent of Indians were believers. Around 98 per cent of Hindus claimed they were pious. Another study, by a youth channel, found that 70 per cent of the Gen Z (the generation currently in their twenties and teens) felt more confident after praying.

The number of believers is growing everywhere except western Europe and north America, and the two religions that make up about 94 per cent of India’s population―Islam and Hinduism―have a median age of 23 and 26, respectively. That is way lower than the median age of the global population, which is 28.

Bipin Dada Kolhe, former chairman of Shirdi Sai Baba Paduka Committee, does not need any statistics to prove the point. “We created a separate queue to help the elderly who we thought formed the majority of pilgrims, but then we realised that barely 5 per cent of the devotees were using it,” he says. “The number of young devotees has dramatically gone up in the last 10 to 12 years.”

And these young Indians certainly seem to have a different take on religion than the ones who went before them―both in why they have taken to it and how they are taking to it.

But how come? For a better part of its post-independence era, India resolutely followed a mindset where religion was respected, but socialism and the state were considered the higher powers, and scientific temperament the lofty ideal to aspire to. Religion was mostly a private indulgence, and at best an electoral strategy, with institutions and intellectuals―and by correlation academic syllabi and the popular thought―all veering towards a society with its foundations rooted firmly in secularism, science and socialism. To put it simply, it wasn’t cool to be religious.

That has been completely upended. In fact, given a chance, the young could give the old a lesson or two on spirituality. “My parents’ generation observe faith like brushing their teeth twice a day. They read the scriptures daily like a ritual because they have been doing it since childhood,” says Anahat Singh, 23, a cabin crew with an international airline. “How much of it is being absorbed by them is actually in question.”

THE ROAD TO SALVATION

“We are living in post-secular times,” says poet and academic Rashmi Bajaj. “This is the age of meta modernism, after modernism and postmodernism that was antithetical to religion. Now, there is a phenomenal shift in the psyche that is palpable and a lot of people are taking to religion and spirituality in a big way.”

The gap between science and spirituality is being bridged by anything from yoga and meditation becoming government tools to alternative schools of thought getting enshrined in the education policy and mainstream academics and research works. “The present dispensation and the policies and they talking about going back to one’s culture and roots, all these things matter as they bring such thoughts to centrestage,” says Bajaj. “Faith is no longer a dirty word, not in political circles, not in intellectual circles, not in academic circles.”

HASHTAG TO THE HEAVENS

The crores of social media posts on the Mahakumbh were not by fervent believers from Bharat, or any concerted IT cell of any political party or fringe organisations. They came from young urban Indians who made it the biggest social media trending topic in India last month.

“The sudden rise of influencers in the spiritual and self-help space underlines the need of younger people to find meaning in this fast-paced world,” says Sahil Chopra, chairman of the Indian Influencer Governor Council. “The popularity of these influencers comes from their ability to offer complex spiritual concepts through bite-sized reels, which help people in everyday life. This has made spirituality more accessible, relatable and even aspirational.”

Anahat Singh would agree. He got curious about religion after attending evening sessions at a local gurdwara where they explained the meaning of the shlokas in the Guru Granth Sahib, but his interest in spirituality spiked after watching videos of Gaur Gopal Das, a monk and YouTube celebrity who does motivational talks straddling the transcendental and the transformational with ease.

Down the value chain, there are many others who could be billed ‘faith influencers’. Like Surya, a digital creator who goes by the Instagram id ‘thesunshineladki’, whose travel content has a vein of religion traversing through it. Her reel on the Mahakumbh had 1.8 crore views, while other related content ranges anywhere from a laser show that tells the story of the Kumbh to the best lassi in Prayagraj, as well as the must-visit temples in and around sangam. She has already moved on to the next big thing on the devotional influencer circuit―Holi. Posting vibrant visuals of Holi in Vrindavan, she invokes FOMO when she asks, “Who all are going this time?”

Harsh Mishra has already reached Vrindavan. The photographer from Lucknow has visited this ‘bubbling under’ temple town earlier as well to catch its unique rituals related to Holi, one of which includes women beating up raucous men and the masses immersing themselves in colour. “It is at the crossroads of devotion and celebration, of finding your identity and at the same time being part of a larger whole,” he says.

The internet and social media are a learning tool for the youth. “Young people look for answers on social media about life and religion that they don’t probably get from their parents or places of worship,” says Faiz Bogani, a Mumbai-based PR professional. He got married a few years ago and the couple’s first trip was to do the umrah, the voluntary pilgrimage to Mecca. The Boganis want to make the trip again soon. “If we go during this holy month of fasting, nothing like it!” he says.

NEW-AGE BELIEFS

Of course, being religious is no mere viral trend. It is no anti-thesis to modernity, either. “Modern life, with its emphasis on individual autonomy and the erosion of traditional social structures, can ironically create a space for the resurgence of faith,” says Anvi Gupta, dean, Sharda University. “Technological progress, while offering solutions and convenience, also brings about new ethical dilemmas, anxieties about job security, and a sense of disconnection from traditional ways of life. These uncertainties can drive individuals towards faith for solace, guidance and a sense of stability.”

The surge of faith among young Indians, even as many in the western world seem to be shunning religion, is no flash in the pan. “In India, this resurgence is particularly pronounced because faith is deeply interwoven with the social fabric, cultural identity and historical narratives. The very process of modernisation can trigger a renewed interest in exploring and reaffirming one’s cultural and religious roots and identity,” says Gupta. “It is not about rejecting modernity; rather, it’s about integrating it with existing belief systems, reinterpreting traditional doctrines in the light of modern challenges and finding new ways to express faith in a rapidly changing world.”

Though brought up as a Christian, Bikila Savanamei, a macrame artist and fashion designer from Manipur, was always ‘lukewarm’ to religion. However, when a friend introduced her to Family of Lord Jesus (FOLJ), a new sect that is getting popular across north India, she was transformed. “Here also they teach the Bible, but you don’t get bored. The teaching is different, less preachy,” she says. “In this church, they don’t judge; the pastor says things like ‘even if you drink, God is not going to hate you’. This way of life is practical and I have learned so many things.”

There is a warning here for conventional organised religion―the youth may be religious, but they are not blind followers.

FAITH CAN MOVE MOUNTAINS

“The shift that is taking place is not into the traditional kind of orthodox religion,” says Bajaj. “Youngsters are relating to the core of the religion where you have life supporting philosophy and positive values that strike a chord. Sharing, caring, belonging―all religions have that and these values are what young Indians are going for, selectively tweaking it to suit their needs.”

While India has always been religious, the current surge has more recent antecedents. The writer Meera Nanda in her book The God Market: How Globalisation is Making India More Hindu attributes this to the intense churn India went through in recent years. She does have a point―from the Mandal strife across urban northern India to the Ayodhya issue that spilled over into many communal riots, Indians have gone through a lot in and around the turn of the century.

The prosperity that liberalisation brought in has come with its own levels of insecurity, making an entire generation turn to faith to tide over the demands and stress of a western-style social and work culture. The globalisation trend also led to an identity crisis among India’s upwardly mobile, who resorted to turning to their identity markers, which were mostly caste, religion and history.

And what all these undercurrents could not do was sealed and stamped once Covid entered the picture. “Covid made people realise that materialism is not all that there is,” says Vibhas Prasad, director, Leisure Hotels. “We started thinking about our lives, and that there could be more to it. That would be the cusp of moving away from materialism to experiences.”

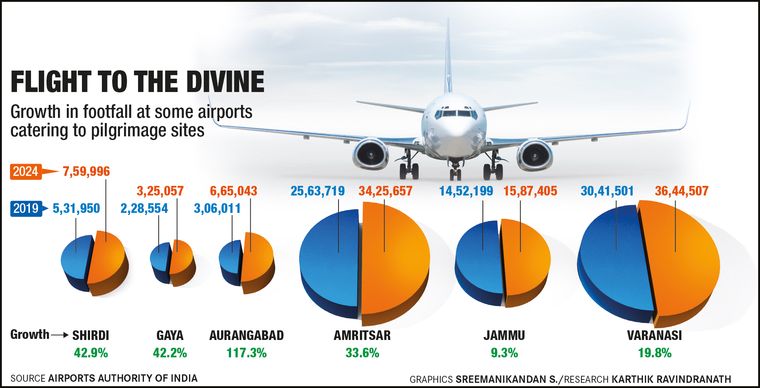

The result? A new-age flurry into faith. The Vaishno Devi temple near Jammu, which used to get around 10,000 visitors a day before the pandemic, now gets up to 40,000 a day, while at the Guruvayur temple in Kerala, the numbers went up from 4,000 to 7,000. The Anjuman Committee at the Ajmer dargah in Rajasthan said that at the Urs in January, up to 30,000 chaadars (a piece of cloth that is offered as a sign of devotion and respect) were presented daily.

A ROOM WITH A PEW

Out of the window along with religious dogma has been the old fashioned approach to pilgrimages―arduous trekking, spartan food and staying in dharamshalas. The post-millennial believer is a bit more refined. Good roads and highways and top hotel chains have transformed the way pilgrimages are done.

This went centrestage last year, when every hotel chain worth its salt announced projects in Ayodhya around the time of the Ram temple consecration. IHCL, which manages Taj hotels, has been actively opening premium hotels in or near pilgrim centres in the past few years. Rival ITC’s next big property will be in Puri, known for the Jagannath temple and beaches that are popular for surfing.

Mid-to-luxury chain Sarovar group has a pilgrimage hotels division of its own, which currently has nine properties in places like Tirupati, Haridwar, Badrinath and Vrindavan. The latest opening was in the Buddhist pilgrim centre of Shravasti in Uttar Pradesh last year. Lords Hotel & Resorts, another chain, specialises in opening hotels and resorts near pilgrim centres. KPMG estimates that religious tourism in India will be worth $59 billion in three years.

THE WAY, THE TRUTH AND THE LIFESTYLE

For the new-age believer, it is all par for the course. “Where else can you do your prayers and aarti in a private ghat along the Ganga?” asks Vikas Nagar, general manager of Pilibhit House, a luxury property managed by Taj on the banks of the Ganga in Haridwar. The hotel even launched a flavours of the Kumbh thali, featuring specialities from each of the four Kumbh Mela destinations (Prayagraj, Haridwar, Nashik & Ujjain) when it realised that many pilgrims who could not make it to Prayagraj were landing up in Haridwar as an alternative. “Today’s pilgrim will mix his pilgrimage with pleasure, and it is no contradiction,” says Nagar. Recently a couple came to celebrate their child’s birthday at the property. After doing their prayers and rituals, they booked an entire section of the hotel to have a party on a terrace overlooking the holy river.

“Today, you can check-in to a luxury hotel and do the temple darshan, also do some sightseeing and come back and try the local specialities or even party,” said Prasad of Leisure Hotels. “Or go to the Coldplay concert in Ahmedabad and the next day go for a dip in Prayagraj. It is a blended experience. Youngsters in new India carry these contradictions very lightly. I may call it a contradiction, but for them, it is natural.”

It could also be pretty syncretic, since what most youngsters are looking for in faith is a sort of self-help guidance. The life of Jishnu, a fitness trainer in Kerala, revolves around pumping iron and attending parties, but come Friday, he goes to pray at Vettucaud church at a coastal hamlet in Thiruvananthapuram. It doesn’t matter he was born and brought up a Hindu.

“The quest is to learn something so that we understand life better,” says Anahat Singh, sounding older than the 23 year old he is. During his free time, Singh goes trekking in Uttarakhand, where his favourite pit stops include local temples with their own backstory.

Singh said his doing so never came in the way of him being a Sikh. “There are a lot of people who won’t do that, but there are also a lot of people who would go to any place of worship if they think they can assimilate what’s good in other streams of belief,” he says.

Not just life’s beliefs, but a lifestyle. This lifestyle takes on anything from devotional music (T-Series’s Hanuman Chalisa is one of the most watched videos on YouTube), hanging out with like-minded devotees, reading self-help books and taking an active interest in history and mythology.

“There is growing interest in genres like mythology and spirituality. We have seen both non-fiction and fiction perform well in these categories,” says Melee Ashwarya, publisher and senior vice president (adult publishing group) with Penguin RandomHouse India.

Whatever the trappings of this surge in faith may be, ultimately it is all about inner peace. Jatin Bhardwaj, actor-turned yoga guru, exemplifies it best. He led a glamorous life as a model and jet-setting flight crew before becoming a successful soap opera star. Then, he gave it all up. “I was on sets 14-15 hours a day and attended parties where I saw stars doing drugs in front of their kids,” he says. “I saw so many successful people, big entrepreneurs, earning so much, yet they were not happy. That is because they were not grounded. And without faith, you cannot be grounded. Surrender yourself to the divine, do good karma and be grateful. That is what matters in life.”