Punjab & Haryana

An associate of Mike Pompeo, secretary of state during President Donald Trump’s first term, recently spoke to an Indian official about New Delhi’s obsession with H-1B visas. He recounted an experience while travelling with Pompeo to India in September 2018 on official business. During his meetings in India, Pompeo focused exclusively on China, wanting to hear more on the topic, but to his amusement, the Indians who attended the meetings kept on talking about visas.

In their push for expanding legal pathways to employment and migration, one thing they missed sharing with Pompeo was a roadmap to address the all-pervasive challenge of steady illegal migration, mostly of semi-educated youth from Punjab, Haryana and Gujarat, through a web of human trafficking networks spanning continents. “When the aspiring elite settle down in the US, it is natural that the less privileged will pursue the same objective in their own limited ways,” said a senior official at the ministry of external affairs.

The problem has now arrived at India’s doorstep. Rakinder Singh, 41, reached the US border on January 15, exhausted and desperate, eyes fixed on the fence that separated him from the American dream. Until recently, crossing it meant a brief encounter with the US Customs and Border Protection (CBP)―detained, processed and then released, free to disappear into the vast immigrant population of the world’s oldest democracy. In fact, the department of homeland security’s (DHS) “humanitarian” approach under the Joe Biden administration was reflected in its guidelines to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) in 2021, asking them to recognise non-citizens’ contributions to state and local communities. For decades, the US immigration system has enabled individuals who have crossed the border illegally to seek protection through the legal system.

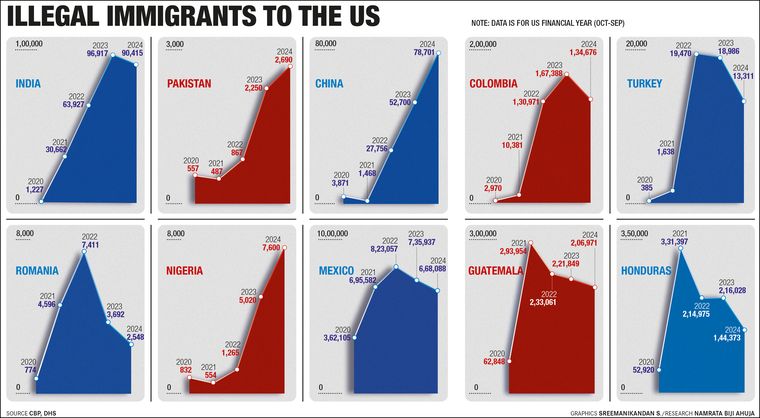

Punjabi speakers, particularly from the Doaba region that lies between the Beas and the Sutlej, where migration has been ingrained in the culture for generations, and Majha in the south of Punjab, with its deep agricultural roots and warrior history, have seen a surge in young men risking everything for a future in America. In villages across Punjab and Haryana, the lure of dollars and the pressure to escape unemployment have fuelled the industry, especially in the last three years. In the financial year 2023 alone, 96,917 Indians were caught by CBP trying to illegally enter the country. In FY 2024, the number was 90,415, and in the months of October–December 2024, it was 18,625.

Punjabi speakers are the largest group among Indian asylum seekers and also the most likely to have their asylum requests approved in American immigration courts compared with speakers of other Indian languages, according to a research paper by political scientists Devesh Kapur and Abby Budiman, published by Johns Hopkins University. Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse, a non-profit data research organisation, has found that 63 per cent of cases involving Punjabi speakers are granted asylum.

But not anymore. Late in the evening on January 20, on his first day in the Oval Office for his second term, Trump signed a series of executive orders making the DHS guidelines infructuous in a violent switch from a “humanitarian” to a “military” response, which has upended the fate of millions. India is only a dot in the vast undocumented immigrant population making a beeline to the border. In the financial year 2024, around 29 lakh undocumented immigrants were intercepted by the CBP, of which Indians were 90,415.

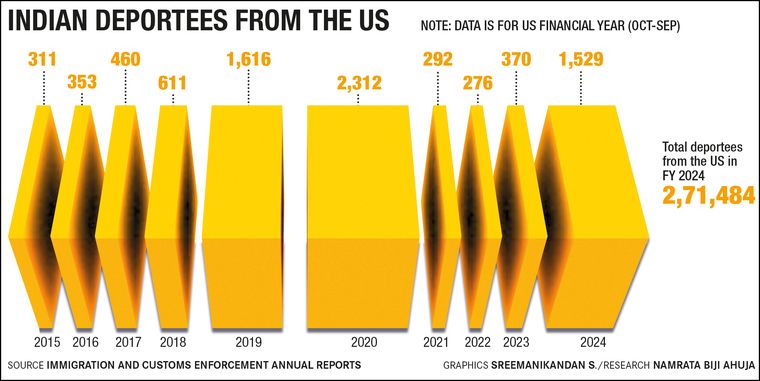

But February saw the road to prosperity turning into a highway to hell and back for Indians as the CBP took away immigrants like Rakinder Singh to a detention centre in San Diego, a city in California. They were housed in a CBP camp, handcuffed and their legs clamped in chains. Here, ICE agents began the process of identifying and removing them from the US. ICE officials put Rakinder and 103 others on a military flight to India on February 5, and 117 more on a second flight that landed on February 15, after Indian authorities confirmed their citizenship. A third flight with 112 Indians arrived on February 16. All three flights landed at Punjab’s Amritsar International Airport.

The reason why military planes, and not chartered aircraft, are used is because Trump has roped in the department of defence for logistical operations, a first since the time of president Dwight Eisenhower. Since January 20, US military aircraft have unloaded undocumented immigrants in Ecuador, Guatemala and India. Colombia and Venezuela have, however, refused to allow military aircraft and have opted to use their own planes to bring back their nationals. Interestingly, deportation flights to Brazil so far have been civilian flights.

The Indian community that once looked towards the US as a safe place to work, earn and live by reaching there through legal as well as illegal routes is feeling the reverberations of the bumpy transition from the Biden era to the Trump era. Trump’s main campaign plank was mass deportations to end illegal immigration. He skilfully linked it with increasing homelessness, crime, rising unemployment and economic woes. Known as a ‘doer’ among his voters, he came up with 26 executive orders on his first day in office, of which 10 dealt with immigration law and policies, which set the tone for treating the threat of illegal immigration as an “invasion” and those without legal status as “criminals”.

Recalling his stay at the detention centre in San Diego, Rakinder said he was not allowed to contact his family or his lawyers. He said a list of approximately 1,800 names was displayed at the entrance of the San Diego detention centre, one of many places where Indian immigrants were being held. Rakinder was detained with 20 Indians and 40 others from countries such as Colombia, Peru, South Africa, Bangladesh and Nepal.

“We were not allowed to shower for days; we used aluminium sheets to cover ourselves at night. They kept the air conditioning ice cold, deliberately left the lights on at night, and conducted security checks three times a day under the pretext of room cleaning, particularly past midnight.” The daily routine at the camp involved waking at 6am for biscuits, room cleaning at 8am, a breakfast of juice, muesli or an apple at 10am, rice or burrito at 2pm, room cleaning at 4pm, biscuits at 6pm, rice or meat at 9pm and room cleaning at 1am. Private guards, who were downright rude, watched them through glass walls all the time.

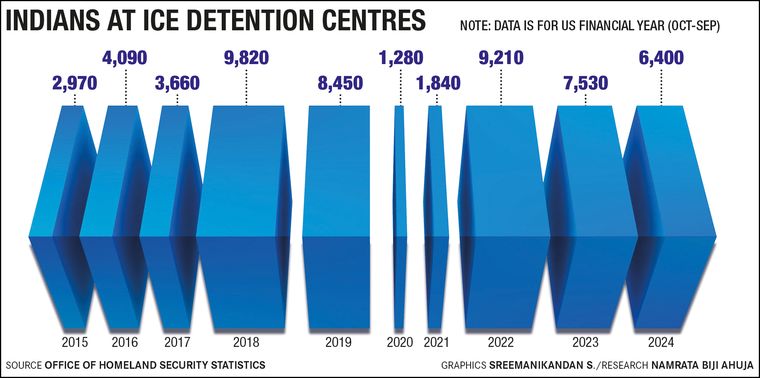

In 2024, ICE’s Enforcement and Removal Operations maintained 129 detention facilities. They house two categories of detainees: those arrested by the CBP on the border and transferred to ICE custody, and those apprehended within the US. At present, 37,684 individuals are being held in these 129 facilities.

Rakinder, the son of a retired soldier, remained sleepless yet alert. “Their intention was to deprive us of sleep. It was only when we were given our bags, handcuffed, and taken in three buses and a van to reach the airbase that I saw ‘Amritsar’ written on the luggage.” Rakinder, who holds diplomas in business management and hospitality, worked in Australia from 2001 to 2020 before the pandemic took his father’s life. “After I failed to obtain permanent residency in Australia, I returned to be with my family during Covid.”

The loss of his father also meant the loss of another breadwinner for his mother, wife and three daughters. Bleak job prospects and mounting bills prompted Rakinder to look for agents to help him reach the US. In 2024, he contacted an Indian agent in Dubai via WhatsApp, who promised to secure him a US visa for Rs45 lakh.

“My husband had little money. We built this house with the help of my sister in the UK,” said Nirmal Kaur, Rakinder’s mother, looking at her house in Gulmarg Avenue in Ladhewali, Jalandhar. “We took financial help from our relatives to send him to the US. Now we are in a bigger crisis.” Being a US deportee, Rakinder cannot travel abroad for at least five years.

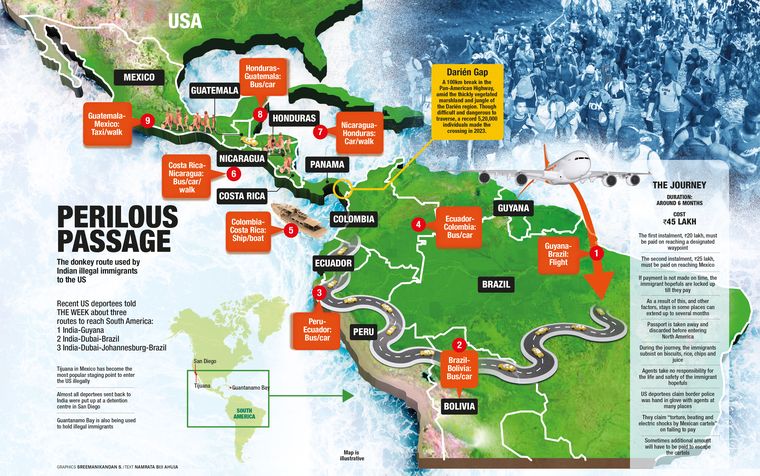

The underground network of illegal immigration that reaches this tiny village in Punjab stretches across continents, thriving under the watch of a mafia―a well-connected web of human traffickers, corrupt immigration officials, and failures at the embassy level that have turned a blind eye to the mass illegal migration to the US. Behind it all lies a multi-million-dollar industry that moves people like cargo across borders. The cost for each Indian ranges from Rs45-90 lakh. Almost all Indians being deported left the country on a valid visa, agreeing to take the circuitous route to Mexico for the final crossing. Police officers have assessed that deportees on the first two US military aircraft departed on valid visas from India, mostly to the UK, Dubai, Guyana and Schengen countries such as Spain, France, Malta and Italy.

Recently, the border crossing from Tijuana, a city in Mexico just south of California, has become the most popular staging point for entering America illegally. This particular stretch of the border allows entry into America in just a few hours, including the waiting period. This section of the border, with ladders to scale the wall or gaps beneath the fence, also serves as an easy pick-up point for CBP officers to apprehend fresh undocumented immigrants.

Unaware of the dangers awaiting him, Rakinder left for Dubai on August 8, 2024 on the instructions of his “agent”, with his family making payments in instalments throughout his journey. His first destination was Johannesburg, but he was unlucky upon arrival as improper documentation led South African immigration officials to send him back to Dubai.

“I had to get my visa papers again. The agents have arrangements at the counters and told me to wait a few days before approaching the right counter.” His second landing in Johannesburg was successful, allowing him to board his next flight to Brazil on August 23. His stay in Brazil was the longest; it lasted one and a half months.

“The local human traffickers collude with immigration fixers and border police at every destination,” he said. “Deals are made before we are released for the onward journey.” By autumn, Rakinder was desperate to reach his destination. Between October and January, he crossed ten countries―Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Panama, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Honduras and Guatemala―before reaching Mexico. At the final stretch, passports, mobile phones and any remaining money are confiscated, and SIM cards discarded, before the Mexican mafia takes over.

Those who survive the journey have shared accounts of legal loopholes allowing undocumented immigrants to buy their way out of detention, sometimes by paying an extra Rs45 lakh. “I knew I would be caught, some paperwork would be done, and I would be freed in a few days. Everyone who has taken this route has settled well in the US, earning and supporting their families back home.” Clearly, the risks involved were outweighed by the opportunities provided by America’s asylum laws.

“The US immigration system allows foreign nationals apprehended at the border who express a fear of persecution or harm in their home countries to undergo a credible fear screening conducted by an asylum officer to assess the validity of their claims,” according to Kapur and Budiman. “Those who pass the initial screening are permitted to present their asylum case in immigration court.”

But this time, many asylum seekers did not get a chance to even present their fears. Ajaydeep Singh, 21, a resident of Baba Darshan Singh Avenue in Amritsar, said he missed entering the US by a whisker. “Trump came to power; otherwise, I would have been in America by now,” he said, confessing that he burnt his passport in anger and frustration after his dream of pursuing an agriculture course and working part-time in America turned into a nightmare. After completing school, his first choice was to join the Army, but he could not pass the exams. “He was a good student; he got 80 per cent marks in class 12,” said Charanjeet Singh, his grandfather, who retired as an inspector in the Punjab Police. “Children from well-to-do families can clear IELTS (International English Language Testing System) and go abroad. Our kids are unable to pass these exams, and we don’t have money to support them. There are no jobs here. We took a loan against our home to pay the agent,” he said.

The agents facilitating visas around the world operate in makeshift shops, local neighbourhoods and foreign shores like Dubai. They run front offices offering legal travel and tourism services in Punjab, Haryana, Gujarat, Maharashtra, Delhi and Rajasthan, with the connivance of foreign counterparts. Interestingly, the agents come from the same social milieu as their victims and understand their pulse, requirements, friends and sometimes even their families. Those running shops in Dubai come through social media advertisements and references, and domestic contacts are handed down by friends and family. “My school friend gave me the reference of Mukul in Kurukshetra in Haryana. He called us to Mahipalpur in June 2024,” said Ajaydeep. Mahipalpur is an urban village close to Delhi’s Indira Gandhi International Airport, dotted with numerous dimly lit, low-range matchbox hotels that serve as cheap options for the crowds that throng the country’s busiest airport. “I stayed there in a hotel for a month, paid him Rs20 lakh, before he put me and some others on a flight to Guyana,” said Ajaydeep.

On July 27, the agent successfully arranged visas for a batch of 12 immigrants, including Ajaydeep, to fly from New Delhi to Guyana, then onwards to Brazil, from where a bus or car journey would take them to Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia. “We sailed from Colombia to Costa Rica on a 20-hour voyage where we had to hide, survive on biscuits and use translation apps on mobile phones to communicate with human traffickers who mostly spoke Spanish,” said Ajaydeep. “Mukul had cut off contact with me. I had been handed over to other agents, who were mostly locals. Sometimes we met traffickers who were Indians.” By the time his journey began from Costa Rica to Honduras, Guatemala and Mexico, Ajaydeep was aware of the systemic corruption―informal dealings with local civil and security agencies―which determined how smooth his journey would be. “The final instalment of Rs25 lakh was paid by my family members to associates of the agent who met them at different locations in India.”

Incidentally, the US attorney’s office for the western district of Texas issued a press release on February 10 saying that a CBP officer was arrested for his involvement in a human smuggling and drug trafficking network at the border town of El Paso. Back home, the crackdown on agents has begun as some families have started approaching the police. “We have registered ten FIRs based on complaints made by some of the US deportees against their agents who facilitated their travels,” said Praveen Sinha, additional director general of Punjab Police. The cases have been registered under the Punjab Travel Professions Regulation Act 2012. The Act mandates that all travel agents must apply for a licence and registration. If the law is flouted, the agent’s licence can be cancelled. There are also provisions under the law for the court to seize their properties.

Many undocumented immigrants prefer Schengen visas to enter the US as they provide ease of travel up to Tijuana. Vikramjeet Singh, 24, a US deportee from Kapurthala, travelled on a Schengen visa to his friend Talwinder Singh in Spain, who arranged an agent to help them enter the US. Hailing from a farming family, Vikramjeet was keen to make a life of his own and support his six sisters. He left from Spain on December 13 for Mexico. Vikramjeet was confident that once he climbed the ladder from Tijuana, he would be on American soil. “But I was caught the moment I crossed over on January 15 and was taken to the detention camp in San Diego,” he said.

The loss of money is often the least of the hardships undocumented immigrants endure. Many recount horrific tales of torture, violence, hunger and helplessness. From the moment they embark on their journey to America, they face immense suffering. Their agreements with agents rarely guarantee personal safety, except for the promise of reaching US soil.

Pushpreet Singh, 18, from Chammu Kalan village in Kurukshetra, Haryana, learned this the hard way. The ninth-grade dropout had been idle at home until his father, Jaswant Singh, decided to borrow money from friends and family to pay an agent Rs34 lakh in instalments. On August 20, Pushpreet arrived in Delhi, where his agent, Sanjeet Marwah, assured him that all paperwork was in order. His journey was planned through Mumbai, Guyana, Brazil and finally Panama.

Upon reaching the Panama jungle, he fell into the hands of a local smuggling ring. They tortured him, claiming they had not received their payment. “I kept calling my agent, begging him to send money, but nothing happened,” said Pushpreet. He said he was subjected to electric shocks and brutal beatings―torture so severe that the wife of one of his captors took pity on him and secretly gave him food. He was released only after his family managed to pay the ransom. His father is furious, blaming Sanjeet for pocketing the money instead of transferring it to ensure Pushpreet’s safe passage. The family has managed to reclaim a portion of it from local associates of the agent.

Mandeep Singh, a 29-year-old from Punjab’s Tarn Taran district, also faced extreme violence on his journey to the US. A chef, Mandeep initially moved to Spain in September 2022 in search of a better livelihood. He was earning well, sending money home, and living a decent life. However, the desire for a brighter future drove him to seek illegal entry into the US. A friend in Portugal encouraged him to act fast before US immigration policies changed under Trump. Trusting this advice, Mandeep left Spain and travelled through Bolivia and Colombia before being smuggled into Panama on horseback. He claims he was held captive in the jungle, deprived of food, and beaten mercilessly until the ransom was paid. “Call your boss,” the trafficker ordered. “Otherwise, we will kill you.”

Mandeep, who had picked up some Spanish during his time in Spain, understood their threats. Desperate, he called home and begged for money. The gang stripped him of everything―his savings of 3,000 euros, an iPhone 14 Pro Max, and even his earrings. Eventually, he managed to reach a hotel staff member, who helped him report the ordeal. However, his nightmare did not end there. When he finally made it to the American border on January 2, it was too late. The CBP apprehended him, crushing his dream of a new life in America.

Unlike Biden, who took a humane approach to the illegal immigration issue, Trump’s militaristic solution is ringing alarm bells for host countries of deportees. The two men entrusted by Trump to fix the issue, Tom Homan, the ‘border czar’, and Stephen Miller, homeland security adviser, have been candid about extreme measures not only to round up those crossing the borders, but also to track down undocumented immigrants who came in years ago and may have settled across the US in labour-intensive roles. There are reports that the Guantanamo Bay detention camp is being readied as a holding space for undocumented immigrants, besides using Panama and El Salvador to house deportees, but no official word has been communicated to Indian authorities yet.

At the moment, the first deportees to India consisted of those caught by the CBP at the border. Indian officials believe that ICE, the agency mandated to track down undocumented immigrants within the US and manage overall deportation, may soon start deporting undocumented Indians who entered in previous years.

Of the 1.1 crore undocumented immigrants from various countries, Indians numbered 2.2 lakh as of 2022. With subsequent interceptions, the total estimated number of undocumented Indians is 4,25,957. On the other hand, the total number of Indians under ICE detention who can be deported as of December 2024 was 2,647, of a total of 37,684 belonging to different nationalities. Estimates available with officials show approximately 1.45 lakh Indians who are not in detention but are being identified for deportation as they crossed into the US in earlier years and are believed to have exhausted legal options to stay for now. This does not include those undocumented Indians held by the CBP and state police forces. Of the 1.45 lakh who are not detained, paperwork for 17,940 is being completed, sources said. Therefore, it can be estimated that, going forward, approximately one lakh undocumented Indians may be identified by ICE alone for deportation in the coming weeks. This leaves open the possibility of more military aircraft carrying deportees landing in India.

Meanwhile, in India, police and intelligence agencies are struggling to track the deeply entrenched networks of unregulated travel agents who continue to send thousands across borders. “At the moment, the challenge is the reluctance of the victims to expose the unregulated travel agents, who can continue to operate under the radar unless the victim comes forward with a complaint,” said Sinha.

In some villages, illegal immigration has become so normal that community members actively seek out agents with successful track records. A sarpanch admitted that villagers encourage young men to find contacts who have already reached the US through illegal means. Once a connection is established, the process becomes a chain reaction, with new hopefuls following in the footsteps of those who have managed to send money home.

Despite the harrowing experiences of many, there is a persistent belief that illegal entry into the US is a viable path to a better life. Balvir Singh (name changed), whose son reached the US through an agent, said the risks were exaggerated. “He was in detention for a few days, but they treated him well and let him go,” he said.

In distant villages where the lines between legal and illegal blurred long ago, whispers of success stories still drown out the warnings. In the meantime, deportees landing in Amritsar are being received by the Punjab Police, their records being reconfirmed by immigration authorities, those with criminal records being sent to custody while others are taken to a makeshift langar area where they are fed dal, paneer, rice, roti and gulab jamun. Many deportees confessed it was their first Indian meal in six months. When the local police ferried deportees back to their families, they were received with tears, shock and broken hearts at seeing them return home, emptier. An unspoken question lingers: what now?