Hasakah, Syria

It is a rainy day, with temperature dropping to 4 degrees Celsius, as I set out for Hasakah, a well-known town in Rojava (Autonomous Administration of North and East Syria) to meet Mohammed Haydar Zammar, the man who recruited the hijackers who carried out the September 11 attacks in the United States in 2001. As we near the prison holding Islamic State detainees, my fixer (translator and guide Ferhan Yusuf) receives a voice message. Kurdish authorities instruct us to proceed to an undisclosed spot.

After I wait for some time in a small makeshift room there, a frail old man enters. Clad in a half-maroon prison uniform, the 64-year-old moves slowly. An officer unlocks his black handcuffs and lets him step forward. I insist on seeing his face as we speak. The officer responds in Arabic before removing the black shield covering his face. He is fair-skinned. His shaved head, light beard and stained, decayed teeth give him a worn, sickly appearance. Zammar removes his thin, black, well-worn slippers, held together by several white knots. Looking at me, he says, “Salam Alaikum,” before waiting for the officer’s permission to take a seat on the blue sofa in the corner of the room.

“Can we talk in English?” I ask.

Zammar looks at me briefly before replying, “I know little English only.”

The Kurdish authorities ask him, “Which language?”

“Arabic,” he responds.

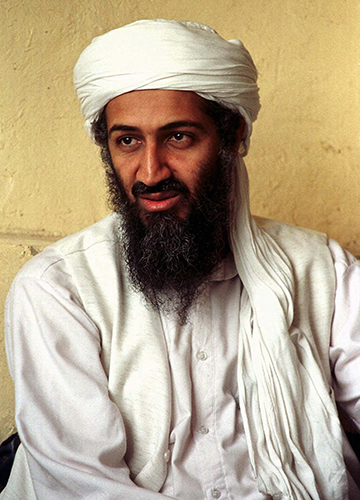

Trained by Al Qaeda leader Osama bin Laden, Zammar played a crucial role in radicalising members of the infamous Hamburg cell in Germany who went on to perpetrate the 9/11 attacks. According to Kurdish authorities, he knew Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi and worked with Abu Mohammed al-Jolani, who took over as Syria’s interim president on January 30.

Once a staunch believer in violent jihad, Zammar has since mellowed. His demands are now simple: he wants a Quran to read in prison and wishes to meet his family.

In his first interview since the fall of Islamic State in 2018, Zammar recounts to THE WEEK his extraordinary journey, which culminated in the stifling cells of a Kurdish prison. Once he begins his story, he is unstoppable. His feeble voice continues, his gaze shifting between me and my fixer. His posture remains rigid, his hands clasped together between his legs, betraying no emotion. His legs remain still, and his eyes reveal nothing. Despite his frail frame, he appears confident and mentally strong.

“I weighed 145kg when I was brought here in 2018. Now, I am just 85kg,” he says. “I have stomach problems. I was in a car accident and was bedridden before I surrendered. Both my knees are weak.”

He lifts his stained jumpsuit to reveal scars from knee surgery. The officer interjects: “He used to be a hefty man. Now he has shrunk. his entire appearance has changed.”

Apparently, Zammar got his beard and head shaved after they had become matted and infested with lice.

Married twice―first to a Syrian woman from Aleppo, who now lives in Germany, and later to a Moroccan woman―he has six children. When I ask about his family, he falls silent, unwilling to share details beyond the name of his eldest son, Adil.

“I want to meet Adil,” he says.

I do not press further, as my instructions are clear: I cannot force the prisoner to reveal information he does not wish to share.

Zammar was born in Aleppo in 1961, and he left for Germany with his sister in 1971. “My father had moved there in 1963,” he says. “I completed my education up to the tenth grade, learned German, and later earned a mechanic’s certificate from Mercedes-Benz. I worked for the company as a young German citizen before moving to Saudi Arabia with my cousin to work in a wind energy manufacturing company.”

Zammar left the wind energy company to join Al Juffali, an automotive firm with a Mercedes-Benz distribution division, where he worked as a receptionist. After two years, he returned to Germany, feeling that the situation in Saudi Arabia was no longer favourable.

During this period, he frequently travelled to Jordan and Syria, and got married to the woman from Aleppo. By then, he was known within his social circle for his interest in joining a militant group called the Fighting Vanguard, an offshoot of the Syrian Muslim Brotherhood that engaged in armed struggles against the Hafez al-Assad regime.

It was at this time that Zammar was introduced to Mohammed al-Bahaiya, known as Abu Khaled al-Suri among his Muslim Brotherhood associates. Zammar drew inspiration from him. A key figure in the Syrian civil war, Bahaiya in 2011 co-founded Ahrar al-Sham, a Syrian Islamist group that fought the Bashar al-Assad government.

With the rise of Osama bin Laden in 1991, Zammar travelled to Afghanistan for the first time to receive military training at one of Bahaiya’s militant camps. “I trained at Al-Farouq camp with Osama bin Laden for two months, then joined the frontline in Jalalabad alongside him,” Zammar recounts, his eyes lighting up with excitement.

He trained as a mujahid, learning to use military weapons and explosives. As I attempt to ask about his relationship with Bin Laden, my fixer Ferhan interrupts: “Do you want him to stop? Don’t you want to hear his full story?”

Zammar, still emotionless, leans forward slightly, listening to Ferhan’s words before continuing. His admiration for Bin Laden is evident. “Osama bin Laden was a simple and respectable man. He was powerful and intelligent,” Zammar recalls.

Between 1991 and 1995, Zammar frequently visited Kabul, Kandahar and Jalalabad, meeting Bin Laden regularly. Inspired by the mujahideen, he also travelled via Istanbul to Syria, Jordan and Germany. At one point, Jordan refused him entry and warned Syria of his mujahideen connections.

Returning to Germany, Zammar became an influential figure among young Muslims in Hamburg. He and a group of young men gathered at Al Quds Mosque, reading the Quran. This group would later become known as the Hamburg cell. Zammar built a following at the mosque, encouraging young men to travel to Afghanistan for militant training. He preached about Bin Laden and Islamic law, but he could never become a preacher himself, as he could not recite the Quran fluently.

According to the 9/11 Congressional Commission Report, Zammar encouraged lead hijacker Mohamed Atta and his associates to embrace violent jihad and persuaded them to travel to Afghanistan for training at an Al Qaeda camp. The report states: “Zammar reportedly took credit for influencing Ramzi bin al-Shibh and the rest of the Hamburg group. Owing to Zammar’s persuasion, or some other source of inspiration, by the late 1990s, Bin al-Shibh, Atta and other attackers Marwan al-Shehhi and Ziad Jarrah eventually prepared themselves to translate their extremist beliefs into action.”

There is no indication that Zammar was aware of the specific plan to launch attacks in the United States. American intelligence agencies say the conspirators found him too talkative to be trusted with the secret, and kept him out of the loop.

Zammar vividly remembers the men responsible for 9/11 but insists he had no foreknowledge of the attacks. “I was in Aleppo when it happened. It had been two years since I last met them,” he says when asked about his links to the attackers.

Following the attacks, German intelligence detained and questioned him, suspecting his involvement. He was preparing to send his wife to Germany via Istanbul when he was arrested. After interrogation, he was released. Soon after, on a trip to Morocco, he was arrested again, reportedly at the request of the CIA, while he was accompanying his second wife to Tangier.

Moroccan authorities held Zammar for 23 days before extraditing him to Syria. He was initially detained at Far’ Falastin, also known as Palestine Prison, in Damascus, where he spent four and a half years without his family knowing his whereabouts. He was then transferred to the notorious Sednaya Prison, where he was sentenced to 12 years.

“The court first decided to hang me. But later, they commuted the sentence to imprisonment,” he recalls. In Sednaya, Zammar was held in solitary confinement, in a dark cell where he could not even see sunlight. After the German embassy in Syria intervened, he got a lawyer. “I told him about my bad experience,” says Zammar. “The prison chief later asked me about my complaint to the lawyer. Thereafter, my condition improved. They took me to a square inside the prison and allowed me to see the sunlight after a long time.”

Zammar also participated in several prison protests, demanding better treatment for inmates. At one point, an agreement was reached between prisoners and the authorities to halt violent punishments. Later, he was moved to Adra Prison, before being sent back to Sednaya. The Red Crescent eventually intervened, ensuring better food and water for detainees like him. While in prison, Zammar, confirm Kurdish officials, met Baghdadi and Jolani.

When asked about Jolani, Zammar says, “I don’t know him personally. But he was in prison with Baghdadi in Iraq. Baghdadi sent him to Syria and ordered him to establish Jabhat al-Nusra. But Jolani made a big mistake. He broke away from Islamic State and formed another group.”

In 2008, Zammar was sentenced to 12 years in prison for being a member of the Muslim Brotherhood. But, in 2013, he was released along with six other Islamists in a prisoner swap for Syrian army officers. His release was negotiated by his old friend Bahaiya, who, by then, had become a leading figure in the Ahrar al-Sham opposition group. Bahaiya was killed a year later in a bombing, allegedly carried out by Islamic State.

Weak and weary after years in captivity, Zammar returned to Aleppo, where his son, Adil, visited him from Germany. By then, Islamic State was rapidly expanding its self-declared caliphate, and in 2014, Zammar joined the group. “At first, I worked in Islamic State’s public relations department,” he recalls. “Later, I became the general head of public relations. Eventually, I was put in charge of all the stations in Al-Bab area.”

It was then that he broke his leg in a car accident. “I was bedridden for a year and a half,” he says. Islamic State, too, was having setbacks. As it was forced to cede territory, Zammar joined a contingent of retreating fighters. Finally, at the village of Darnij, in Deir ez-Zor in eastern Syria, Zammar gave up and surrendered to the US-backed Syrian Democratic Forces.

“I was very sick. I didn’t have a car. My wife was pregnant. What could I do?” says Zammar. “I had no option.”

When asked about Islamic State’s presence in India, Zammar claims he has no knowledge of an Indian branch of the group, but recalls meeting a man from Kashmir. “After I was arrested, I did not meet anyone from India,” he says. But he admits to having had Kashmiri friends in prison. When pressed for details about them, the Kurdish authorities stop him from speaking. “Should I not say?” he asks in Arabic, and the conversation abruptly ends.

According to Zammar and other sources, three Indian men―possibly Kashmiris―are currently held in Hasakah prison. In 2019, when I visited the prison in search of Indian detainees, the guards mistakenly introduced me to a Pakistani detainee named Chaudhry, thinking he was Indian. The Indian prisoners, who, sources say, are in their late 30s or early 40s, joined Islamic State between 2014 and 2016.

As the interview concludes, Zammar suddenly remembers another chapter of his past. “I forgot to tell you, I also trained in Bosnia in 1995,” he says. “It was because of the Croatian attack on Muslims. The Serbians also attacked Muslims there. So, as a true Muslim, I went to Bosnia and joined the Mujahideen Battalion. I fought alongside them against the Serbians and Croatians. After we won, the Americans and NATO stepped in, negotiated with all sides, and settled everything.”

An hour has passed, and the Kurdish authorities in the room instruct Zammar to leave. As he turns to go, I ask once more, “You really don’t know English? Won’t you tell me about your Indian friends?”

But he chooses to remain silent. “Tell me about the Kashmiris you met,” I press again.

The guards intervene and order him to leave. A man enters, places Zammar in handcuffs. Holding the door open, Zammar steps out of the room, slips his feet into his worn-out black sandals, and walks away with the guards, perhaps still clinging to the hope of seeing his family again.