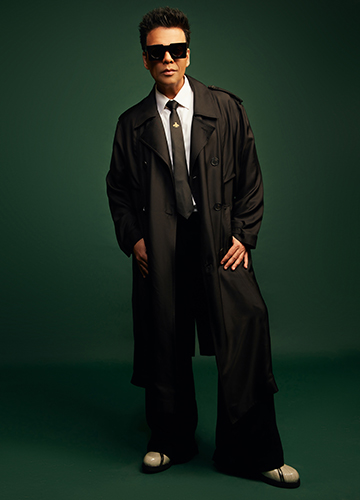

Can Karan Johar ever not be in the news? It is almost impossible. Ever since he introduced himself to us in 1998 with his first film, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, under his father Yash Johar’s banner—Dharma Productions—Karan Johar has been front and centre of all things entertainment. For over 25 years, he has been a director, producer, talk show host, reality TV judge, businessman and investor, entertainer, envelope-pusher, controversy-chaser, Bollywood representative and more.

Dharma Productions clocked 25 years under Johar in 2023. It also clocked in its 50th production, a film directed by him after seven long years. Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani was among the many hits in a blockbuster year and won him more critical acclaim than any film he has made.

Johar, 51, is not your average multi-hyphenate. The Hindi film industry has not seen a tour de force like him. Johar has turned his father Yash’s medium-sized business into a mega empire. Johar’s Dharma produced 50 films in half the years; launched Dharma 2.0, an ad film arm in 2016; Dharmatic Entertainment in 2018 for OTT content; and Dharma Cornerstone Agency or DCA, a talent management agency that manages most young stars, in 2020.

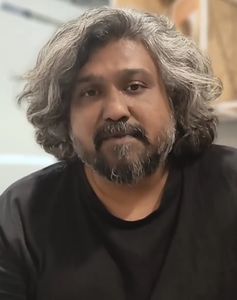

“Dharma under Karan Johar was a startup before we knew what startups were,” says director Shakun Batra, smiling. The 40-year-old has made three films and a documentary under the production house. “Karan was a young kid who hired a bunch of young kids, backed their ideas and stories and created a great entrepreneurship,” he says. “Karan and his partner Apoorva Mehta were not even 40 when they started backing other people.”

I AM MEETING Johar at his newly refurbished home in Union Park, just off Bandra’s Carter Road. The house is spread over three floors—three interconnected flats of an apartment building. Johar is at ease in an expensive black tracksuit, and with a small army of staff in attendance. He greets me with a hug, and offers, “Coffee?” Who can toss up a chance of a ‘Koffee with Karan’, his uber-popular talk show that made its debut in 2004?

Did he know 25 years ago what he would be creating? “Oh my God, no,” says Johar, laughing. “My parents were vehemently against me being part of the film business.” His father had a tiny export business, selling wrought iron to America and France. “Simultaneously, he began to produce tent-pole films,” recalls Johar. “He had several setbacks and the films didn’t work. My mother (Hiroo Johar) kept saying I needed a stable job, a stable salary, and that films were not a profession for anybody. She wept when I signed up for an arts degree and insisted that I join a commerce college instead. Like a good Sindhi Punjabi boy, I had to listen to her.”

Johar topped the state in commerce, and got into a leading management school. But he decided to pursue films. “I grew up watching Hindi cinema,” he says. “I repeat-watched films on VHS cassettes. I would take the house help with me to cinema halls. Cinema was a great sense of entertainment for me, not a professional goal. But you don’t write your own destiny, the universe does.”

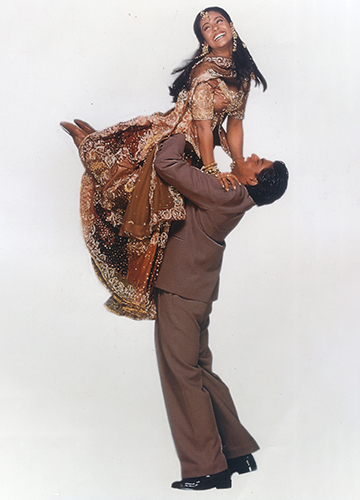

Johar was 26 when he made Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, which won the National Award for best popular film. He followed it up with Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham in 2001, another blockbuster which won multiple awards. Months after Kal Ho Naa Ho’s release (produced by Johar and directed by Nikkhil Advani, with two National Awards this time) in 2003, his father died of cancer. He was 31. “I had never involved myself in the business aspect of things. I couldn’t sign a cheque and I had never met our chartered accountant,” he explains. “I called my best friend from school, Apoorva Mehta, who was working in finance in London. His wife and he packed their bags and returned.” Mehta became, and remains, the CEO of Dharma Productions. He also remains Johar’s number one adviser. “He is my financial keeper, my financial policeman,” says Johar, smiling. “He became like a sibling.”

Mehta and Johar have had an enviable friendship and partnership, one that deserves a Bollywood film of its own. Johar was asked to change divisions when he was in class six, and was worried about not having any friends. The teacher asked the new class for a show of hands to volunteer a friendship with Johar. Mehta’s hand shot up first and Johar was asked to sit with him. “For most people, their careers are happy accidents,” says Mehta, 52, smiling. “Mine was one, too.”

Mehta’s father died when he was just 17, pushing him to join the family business of copper wires and dyed imports. After attending college in the morning, he would shuttle between Masjid Bunder and Andheri, two ends of bustling Mumbai, to attend the family offices before winding up only at night. He would devour the pink papers and was excited by entrepreneurship. “I got married, and decided I needed to get an MBA to have a real career,” he says. Aditya Chopra was opening an office in the UK for Yash Raj Films and Johar got Mehta a job there. “I just told my family I am going to do an MBA in London. I joined Yash Raj, and attended my MBA classes in the evening,” Mehta says. Now the Mehtas and Johar live in the same apartment building.

“We made some mistakes, we learned. We fell flat, we rose,” Johar says of their partnership. “There can never be two decision makers,” Mehta avers. “While Karan enjoys his creativity, I don’t have the patience to be on a film set. I enjoy the business of filmmaking, raising money, deciding expenditure, and distribution. Karan gives me complete freedom and we never cross each other’s paths. But Dharma is Karan Johar. The creative person is indispensable, everyone else you can hire.” Mehta admits to having received offers from other production studios, “but Dharma is home”.

The two created the film factory that Dharma is today. “I was very encouraging to first-time filmmakers,” says Johar. “In all this chatter about nepotism, people forget that of the 25 directors I have introduced as first-time filmmakers, 80 per cent to 90 per cent have no connection to the industry. But you get very little credit for cinematographers, stylists, production people that you give opportunities to.”

JOHAR’S STRENGTH IS being a people’s person, not just in pleasing them but trusting them with work. Batra recalls how he got to meet Johar—actor Imran Khan had read the script of his Ek Main Aur Ekk Tu (2012) and liked it; then, at a party, Khan asked Johar to look at the script. “Within two weeks, I had a meeting with Karan,” says Batra. “He was so friendly; you forget you are sitting with Karan Johar.” Batra adds this was not the time for big studios, and Johar had the vision to grow.

“My father always said that people need people,” Johar credits it as a business lesson. “You can’t tell different stories, deal with different temperaments, unless you have people skills. Only 10 per cent of me is talent, the rest is managing people.”

Johar says he was lost 25 years ago. “But I was confident in my writing. The written word is stronger than anything else,” he says. This was also a time when celebrities were not as affected by things such as social media or so many critics. “Only an audience could judge a film,” he says. “Now films have moved to digital, silence has moved to PR. A simple, strategic, vanilla release has become a huge marketing campaign,” he says, laughing. “There was no such thing as publicists, agencies, media junkets. There was no Amazon or Netflix or Disney + Hotstar. But now there is a lot more discipline, there is a lot of professionalism. There is a lot of advancement but at the cost of simplicity, honesty and conviction. Now, conviction has to be created. I have to reinvent my conviction and my innocence.”

Reinvention has kept Johar on top of his game. The big fish cannot just be a big fish, it must also now climb the tree. “To be relevant is most essential,” he says. “You are relevant when you can cater to every generation. I surround myself with people of younger generations and absorb what they say like a sponge. The new generation is always brighter than the one before. They may swipe left or right on Tinder, but their level of intensity is the highest. They are not flippant; they are passionate. This is why they are so angry on social media, or about the political climate. Anger is important for artistic achievement.”

Love him or hate him, but dare not ignore him. “Because of the kind of personality I am, there will always be emotions that will follow that will either be love or hate. I am okay with both. What I am not okay with is indifference,” he says. “I am fine if you think I am a gossiping chap who giggles on talk shows, or someone who wears these (fashionable) clothes, or someone who is entitled and full of himself. As long as you are still talking about me, as long as you are still talking about my work, as long as I am creating pop culture—that is relevant.”

A couple of National Awards, a Padma Shri and several independent awards later, why is Johar still seeking validation? “When you finish a shot, you want to know what others think of the shot. Creative people seek validation all the time. Some voice it, some don’t,” he says. “The drive comes from insecurity. If you aren’t insecure then part of your artistry is dead. If you wake up every day questioning whether you did right or wrong, you are a breathing artiste. If you are overconfident, you are already on a ventilator.”

MUCH OF THIS DRIVE has led to Dharma’s expansion. Puneet Malhotra—nephew of designer and friend Manish Malhotra—suggested that Johar start a new division to manage his brands. Johar asked him to run it. DCA, which Johar co-owns with Bunty Sajdeh, has former journalist Rajeev Masand heading it. “Masand was a critic, but he has a head for cinema content. He has worked out fantastically for us,” says Johar. “Every expansion has teething issues. But once you get it right, it’s great for your company’s brand value.”

Dharmatic was an immediate extension as the advent of streaming platforms turned films and shows into content. Business is divided 70:30 between Dharma and Dharmatic. Somen Mishra heads project development for film and digital, and takes care of fiction, while Aneesha Baig takes care of nonfiction. Dharmatic has been incredibly active in producing shows and films such as Guilty (film; 2020), Ajeeb Daastaans (anthology; 2021), Searching for Sheela (documentary; 2021), Meenakshi Sundareshwar (film; 2021), The Fabulous Lives of Bollywood Wives (series; 2020 and 2022), The Fame Game (mini-series; 2022), and Koffee With Karan (2022-23).

“Somen has brought solid resources of writers and directors into the company,” says Johar. “We are working with some people we never imagined we would be working with. Vasan Bala is making a film for us (Jigra, slated for a 2024 release, starring and co-produced by Alia Bhatt), Neeraj Ghaywan is another. And so is Sandeep Modi, director of The Night Manager (series; 2023). Selecting Somen was also exciting for us because he told me he fell asleep watching Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham. I loved his honesty.”

Bala, 45, the acclaimed maverick director of films like Mard Ko Dard Nahi Hota (2018) and Monica, O My Darling (2022) agrees. “I was neither inspired nor begrudged by Johar’s films, as we are just different types of storytellers,” he says. “But it was refreshing to see someone who didn’t come with the approach of a big producer, that I should either take his script or leave it. He asked me what I liked to make. I was convinced this would be an equal creative collaboration. He has backed me and he is letting me run with it.” Bala says this trait of Johar has allowed him to have such a long, evolving career.

Critic Anupama Chopra remembers a time when Bollywood was just a monolith. “I started working just a little before Johar, Aditya Chopra and Sooraj Barjatya,” she recalls. “Bollywood films were stars, songs and the good going [up] against the bad. There was a sporadic outlier, like Baazigar (1993). Dharma started the same way. That DNA is still maintained, with costumes, stars and glamour. But this year they will be releasing Kill. It is a horrific, violent genre film. The Dharma bouquet is now so many things.”

The Dharma umbrella employs around 300 people. They sit in three office spaces spread between Bandra Bandstand, Khar and Andheri. Half of these are from creative fields, and the other half are from corporate or business backgrounds. There are also in-house legal, marketing, financial and public relations teams.

Over the years, Dharma Productions (along with Farhan Akhtar and Ritesh Sidhwani’s Excel Entertainment and Aditya Chopra’s Yash Raj Films) has been crucial in giving Bollywood a more professional energy. The introduction of foreign studios and streaming platforms has helped, but production houses like Dharma have led from the front.

“I would credit Apoorva for streamlining the company,” says Johar. “Bollywood has progressed, so one has had to organise one’s company, too. One production house sets the ball rolling and then everyone follows suit. Excel started this strong AD (assistant directors) culture with Dil Chahta Hai (2001). Then Aamir Khan and Apoorva Lakhia took it forward with Lagaan (2001). We set the ball rolling on how you can do multiple films under one production house. Yash Raj and Dharma were the pioneers of the model of doing films under a studio.”

JOHAR’S SUCCESS, AND being an outspoken public figure, has made him a de facto spokesperson for the Hindi film industry, too. Anupama Chopra says there is more to him than just his films and shows. “Johar is truly impacting the cultural landscape of Hindi cinema,” she points out. “He is genuinely a key architect of the Bollywood narrative. Just like he and Aditya Chopra were architects of the Shah Rukh Khan legend. The Raj-Rahul persona was created by both of them. It was like Vijay for Amitabh Bachchan in the 1970s. Johar is such an arbitrator of what’s cool, what’s not, and who’s in who’s out.”

“I am not stage-shy,” he admits. “From the beginning of my career, I had been invited to speak on panels and even at Ivy League universities. I have spoken about the history of cinema, the relevance of it, what a soft power it is. Now I am being asked about digital versus film everywhere I go. I have attended film festivals like Cannes, Berlin, and I have been invited to the World Economic Forum in Davos, too. I met people I may have never crossed paths with.”

Much of this comprehensive access is also because Johar has always refused to be boxed under one label. Only actors were supposed to shine, filmmakers were to remain behind the scenes. But here comes Johar—intelligent, quick-witted, dressed like a fashionable peacock—holding everyone in a rapture.

“In 2001, I was asked to host the Filmfare awards. What started as something I did for a lark became a legit part of personality,” he says. “Hosting awards got me into hosting TV and reality shows. I started Koffee With Karan in 2004 thinking since I love talking to people, I may as well get paid for it. Now I tell people if you love something, pursue it, because it sticks,” he says. “Don’t fight the shine, don’t fall prey to stereotypes. Who said that an actor must behave in this manner and a filmmaker in that manner.”

JOHAR IS NOW a celebrity ‘brand’, like a movie star. His wealth is estimated at Rs1,700 crore, much of which comes from filmmaking. He also makes a sizable figure from advertisements, talk shows, social media endorsements and events. He admits he had impulsively signed off the intellectual property rights of Koffee With Karan to Star India and jokes “they can pursue it with Karan Thapar if they like”. Even the rights of Johar’s use of the term ‘rapid fire’ is owned by them.

His films have succeeded because of his great sense of scripts and storytelling. But in aiming to be a cultural moment in time, his films appear dated. Kuch Kuch Hota Hai is now remembered as the story of a tomboy who got the guy after she started wearing saris, or Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham glorified a bully of a patriarch.

“I think the evolution is mine, but it is also the growth of cinema in general,” he reasons. “When I made Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, it was me deriving from cinema. What we call ‘stalking’ today, a leading man chasing a leading lady, was just called ‘romance’ at one time. Kuch Kuch Hota Hai had its gender politics all wrong, I admit it.”

Even his films with ‘mature’ themes received mixed reviews. “People said I endorsed infidelity through Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna (2006), but I said you can’t endorse something that’s already sold out,” he says. “I also made My Name is Khan (2010) that was based on the secular fabric of our nation, or the misinterpretation of religion, but nobody addressed it. After that I wanted to make something younger, so I made Student of the Year (2012) with all newcomers—Alia Bhatt, Siddharth Malhotra and Varun Dhawan. I knew I wasn’t moving any cinematic mountain with it. It wasn’t going to be remembered as a great film, but a fun film. Ae Dil Hai Mushkil (2016) was my most personal film, I had an unrequited love that broke me.”

With Rocky Aur Rani Kii Prem Kahaani, which speaks against the current cancel culture fuelled by social media, Johar says he has corrected his politics. He admits he was taken aback by its success. “I had told my marketing team to take it easy with me, as I was feeling quite fragile directing a film after seven years,” he says. “But when they shared the reviews, it really was the best-reviewed film of mine.” The film ended up making over Rs350 crore in a year that saw mega blockbusters such as Shah Rukh Khan-fronted Pathaan and Jawan (both crossed the Rs1,000-crore mark), Ranbir Kapoor’s Animal (nearly Rs900 crore) and Sunny Deol’s Gadar 2 (Rs525 crore).

IT IS PERTINENT to ask Johar about the economics of filmmaking, considering 2023 saw Hindi films bringing in record amounts of money (reportedly Rs12,000 crore) to an industry that was written off just the year before. Is filmmaking today a manufacturing game? Can profit be estimated according to marketing and PR spend?

“Technically, there are four verticals you need to put on a chart when you are making a film,” explains Johar. “One is recovery from satellite rights or television rights, which is at an all-time low now. The second is digital recovery which are the OTT platforms; this is a large part of the pie. Then there is music that also gives you money if you are a filmmaker known for your music. And the fourth is your estimated box office potential. The best model is when you budget a film accordingly.” But, he adds, nothing can salvage a bad film, and nothing can stop a good film. “Not even marketing,” he says. “But filmmaking is not just about recovery, it is about prestige. You may do the maths and not lose money, but you may lose prestige. So, filling those theatres is still important.”

Despite the clever computations, Johar remains an old-world filmmaker. “First, they said cinemas are dead. Now that digital is low, they say cinemas are back. There are no theories,” he says. “The audience can shock you or surprise you. But their word is final.” Johar highlights recent small films that have done exceptionally well, like Vidhu Vinod Chopra’s 12th Fail and Meghna Gulzar’s Sam Bahadur. “A good film can break every myth and shatter any trade analysis. There are many Indias and you never know which India is tapping into your content,” he says, smiling.

The director and producer in Johar’s head are often in conflict. His company has often been saved by Mehta, he admits. “Each time I make a film I wonder how this film will be remembered,” he says. “All the films we remember are not necessarily golden jubilees. We remember Ghar (1978), Ijaazat (1987), Lamhe (1991) and Masoom (1983). Commercial success is critical, but leaving behind a legacy of love is everything.”

If someone pays Rs100 for a cinema ticket, where does that money get divided? “First in tax, then to the distributor, then the commissions,” he explains. “The producer gets home about Rs35 to Rs40, this includes the salary of the star. You have already put everything into your ATL (above the line budget), so this is how much comes home.”

Is it more economical to produce one’s own film or have a streaming platform commission one? “It is more profitable to make your own film, and this is why theatrical releases will always come out tops,” he says. “You can sell this to an OTT platform eight weeks after its theatrical release. Then there are films that you make specifically for streaming services, then you listen to their pointers. The money made here is not very large. Going to the theatre and then going digital is more profitable.” Moreover, streaming platforms do not disclose the drop-off rate when garnering data. A film or a series may be trending at number one, but that does not indicate audiences have watched even 20 per cent of the film.

Is there a film he wishes he had not produced or had produced differently? “It is a tough question because I will hurt the person who made it,” says Johar. “There are films that were emotional decisions. The only film I wish we had packaged differently was Kabhi Alvida Naa Kehna. I tried to bring commercial elements like big song sets and massive stars, but it is an intimate film. If I could make this film again, I will correct it.”

Johar says he can smell a flop before the film’s release. “We do a lot of market research screenings, so one gets an indication. I still feel sad, but I have to be there for the lead actor and the filmmaker first. I will survive, but their careers could break,” he sagely says. “Money comes. One film failing won’t change my monetary destiny. Failures have to be followed by successes if you are playing this game.” Johar gives the example of when Kalank flopped in 2019, but Dharma ended that year with Good Newzz, one of their biggest hits ever. “This is something no amount of chanting or therapy can teach you: if you can treat success and failure with the same level of intensity, you will be fine,” he says. “Resting on your laurels or getting bogged down by failure are both detrimental. If failure happens, analyse it, lament it, but move on. Moving on is critical.”

Much of Bollywood is dominated by the superstar phenomenon— expensive actors who consider themselves so bankable they drive up the production budget. “Many actors are working under this cloud of delusion, and delusion is a disease with no vaccination,” he says, laughing. “At the negotiations stage itself I say this is not working. There are massive stars that are very viable for sure. But there are also actors who believe they deserve a certain number. I certainly want to pay an actor their market value, but I don’t want to be taken for granted.”

Major production houses have their in-house legal departments, too, now courtesy of the large number of FIRs being filed against the industry. “People get offended so easily,” he says. “We don’t even know who we are offending half the time, but people are filing FIRS from various parts of the country. Our legal teams tell us whether something will be a problem. Sometimes there is a brand in the film that you cannot be derogatory about. Or, one cannot talk about a community or a religious practice that may seem offensive. Even when you make a film on the Indian Army, we need to get those permissions in place.” The ‘Radha on the dance floor’ song in Student Of The Year had objections on religious grounds. In Kabhi Khushi Kabhie Gham, a scene showed the national anthem being played, and an objection was raised as to whether the audience should stand up when that scene came on. “I think that case is still being fought somewhere,” he says.

JOHAR HAS BROUGHT homosexuality to mainstream cinema in his own way—whether it was acceptance through comedy in Dostana (2008) or Kal Ho Naa Ho or the absolute brilliance of the gay character of Rishi Kapoor in Student Of The Year. But he has always sidestepped discussing his own sexuality. He has also not politically committed on decriminalising homosexuality or fought for same-sex marriages.

“I don’t want such a large part of my life to be used as a headline. I think that’s what it will become, and then the impact of all that I do will be lost,” he says. “I have never hidden who I am. I would rather do the work on ground level. I believe the impact of what I have done through my cinema, through the things I have said in my book (An Unsuitable Boy, co-written with journalist Poonam Saxena), has already touched people in a way where they were able to start conversations with their peers and parents. I will continue to push that envelope. Me saying anything will just be sensational, it will just be ridiculed and reduced. But cinema is a far more impressionable medium.”

Dharma, says Johar, feels very strongly about the LGBTQIA+ community. “We deal with sexuality in as dignified a way as possible. As a company, we feel passionate about telling the stories that could make you awkward. Right from ‘Geeli Pucchi’ (a short film by Ghaywan starring Konkona Sen Sharma and Aditi Rao Hydari) in Ajeeb Daastaans to Kiara Advani having an orgasm to one of my songs in Lust Stories (anthology; 2018), we want to push boundaries,” he says.

There is a feeling that the film industry should have aligned to bring about a social or a political change, or when governments or their spokespersons try to ban a film. “I think the industry comes together when we have reason to,” clarifies Johar. “Of course, there are times I do feel we can come together more often. But we did, during the pandemic. We did come together against certain news channels that were saying inappropriate things about Bollywood. We got together and the bashing stopped. We were collateral damage for nothing.” He is referring to the 2020 defamation filed by four film bodies and 34 film studios before the Delhi High Court against certain media houses to “refrain them from making irresponsible, derogatory and defamatory remarks against Bollywood as a whole or members of Bollywood, and to restrain them from conducting media trials of Bollywood personalities”.

BEING AMONG THE first celebrities in India to have children via surrogacy is commendable. Johar is father to Yash and Roohi, who were born in February 2017. Yash is his father’s name, and Roohi is an anagram of his mother Hiroo’s name. “When I was 40, my mother asked me what my life plans were since marriage wasn’t on the cards,” he recalls. “I told her I really wanted to have babies. She was wonderful [about it], but I was taking my time. She reminded me again a year later. I only told her about it once the doctors informed me that three months of pregnancy was complete. The babies were expected in April, but they arrived in February. I had to officially announce their arrival from a flight to London once I knew a couple of newspapers were going to carry the story. I could go to the hospital only a month after.”

I was one of the two journalists who broke the news. I tell him how thrilled I was with the news, even though he and I are just professional acquaintances. “I am used to trolling, but surprisingly, my kids were met with so much love,” says Johar, with a smile. “Even now, when I put up anything about them, there is not a single negative comment.”

BEING A MEGA brand has made Johar invest in several companies, such as Tyaani jewellery, Nothing phone, a Mumbai restaurant called Neuma, and a lipstick brand called Pout. “There are some business opportunities I am leveraging as a result of the brand value I have created,” he says. “Everything I have done represents certain parts of me, my interests or aesthetics. I don’t want to be part of something I don’t understand. So don’t put me in a bitcoin company.”

The fashionable Mr Johar experiments with colour, large glasses, au courant styles, even heels once, and features regularly on the ‘best dressed’ lists. “Clothes are a ridiculous indulgence, you know, because of the kind of money that goes into buying them. But I enjoy them,” he offers. Much of his glamour also comes because he loves the movie industry, and the movies are a beautiful place. “I think if a leading filmmaker is talking about his next appearance, then it deserves importance. I love that men are also waking up to fashion. I have always said men playing it safe are not playing the game at all,” he says. “Vanilla is boring. I have never shied away from shine. You have to walk out of your house feeling great in what you wear.”

His Koffee With Karan, in its eighth season, is as much of a zeitgeist as his films are. It moves with the times, keeps up with woke conversations, and allows audiences to view the bare bones of movie stars, despite its glamorous dress code. “I feel the stars feel safe with me, even though the show ends up being a PR nightmare for them sometimes,” he says, laughing.

Everyone is dressed to please, everyone compliments their competition, and everyone is here seeking the audience’s approval. Everyone is seen as a professional with a new work ethic, not just a celebrity. “The younger generation is certainly much hungrier for work,” he says. “They will not let their personal lives affect their professional decisions. Ranveer Singh once told me that Koffee With Karan builds the perception of the kind of human being you are in a way that no other show can. But there is also voyeurism, you hear about anecdotes that happened in our homes.”

Johar has built his empire completely without the nudge of investors. “People have made gracious offers, but we will wait,” he says. “We plan to go bigger, wider, and create more content across platforms—digital, cinema or advertising.” He is also developing a new film to direct this year.

“By the time I throw my 60th birthday bash, I want to be a wider conglomerate,” he says. “And yes, I will still be in a sequined jacket.”