Congress veteran Kamal Nath, an old warhorse who has won many a battle in the political arena, electoral and otherwise, is fighting the toughest and most significant contest of his career. The 76-year-old is leading the Congress’s campaign to win Madhya Pradesh―the state has been under BJP rule for about two decades, except for a 15-month period after the 2018 elections when Nath was chief minister.

The party has once again put its faith in Nath. In what is a rarity for the Congress, it has named him the chief ministerial face for the elections. Usually, the party line is that the MLAs decide the chief minister after the elections. What is also surprising is the general acceptance of Nath’s leadership in the state unit, which is quite the feat for a party ravaged by vicious infighting in the past.

The seasoned leader, with a reputation of being a hands-on politician and a go-getter, has set himself a punishing schedule. Ever since pandemic restrictions were lifted, he has been on a hectic tour of the state, going right down to the block level, meeting people and also party workers. He has sought to amplify the perceived dissatisfaction with the Shivraj Singh Chouhan government. The Congress’s assessment is that there is now fatigue associated with the BJP rule as also with Chouhan’s own image as a leader and administrator.

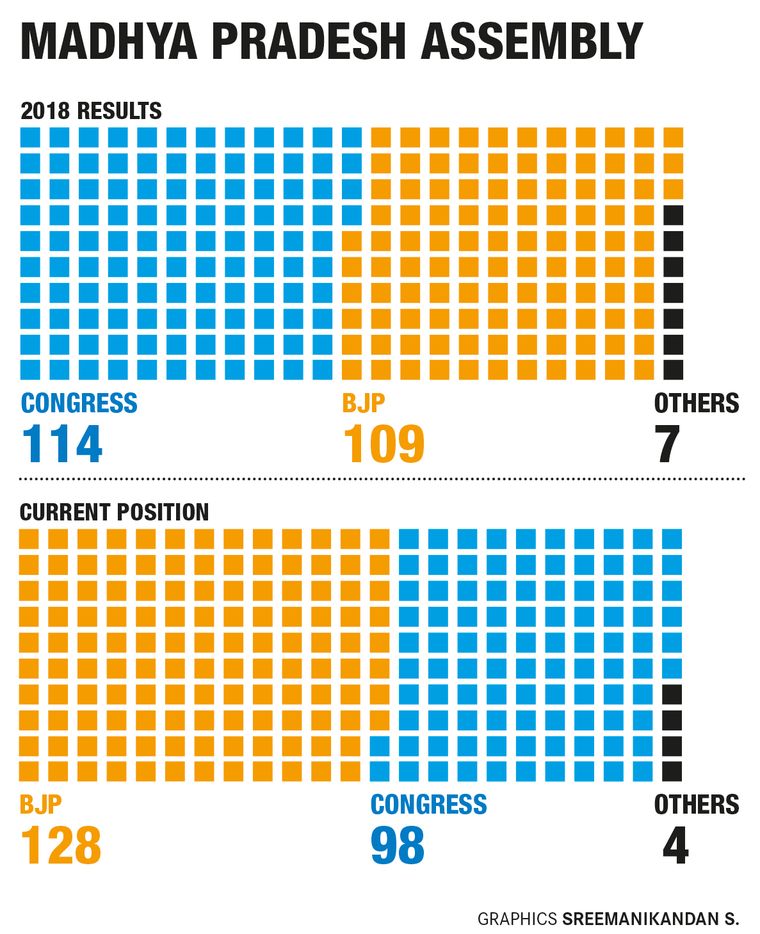

In the period after Nath’s government was toppled, in March 2020, he faced many challenges. MLAs were leaving to join the BJP and the party did not taste much success in the byelections.

The first indication that the tide was perhaps turning in the Congress’s favour came from its wins in supposed BJP strongholds in the 2022 mayoral elections. There had also been efforts to woo back leaders who had left with Jyotiraditya Scindia; the fact that some prominent ones returned was a morale boost. Samandar Patel, a leader known to be close to Scindia, made his way back at the head of a cavalcade of around a thousand cars from his constituency Jawad to Bhopal, a distance of more than 400km.

Closer to the elections, the Congress has carried out a Jan Aakrosh Yatra to highlight issues such as corruption and the Chouhan government’s alleged failure to act on issues of importance to farmers, youth, women and the marginalised. Central leaders such as party president Mallikarjun Kharge, former party chief Rahul Gandhi and general secretary Priyanka Gandhi Vadra have addressed rallies, but, taking a cue from the party’s successful Karnataka campaign, they are playing a secondary role. Nath is the prominent face on all campaign material and local issues are at the forefront.

Interestingly, Nath apparently said no to the first public rally of INDIA (Indian National Developmental Inclusive Alliance), which was to be held in Bhopal. It is learnt that he did not want any distractions for himself and the state unit.

Nath’s outreach has been based on a slew of populist promises, mainly his 11 guarantees that he promises to fulfil if voted to power. These include a monthly incentive of 01,500 to women, LPG cylinders at 0500, waiving farm loans, free electricity up to 100 units, restoration of the Old Pension Scheme, caste census and withdrawing cases filed against farmers during the agitation against the three contentious farm laws. He has sought to set the agenda and be in control of the narrative, and has not lost a chance to take a swipe at Chouhan for allegedly coming up with the same schemes that he announces.

“If you look at the Congress manifesto, all the aspirations of the people have been taken care of,” said Pratap Bhanu Sharma, vice president of the Madhya Pradesh Congress. “We have left nothing for the BJP to declare.”

The BJP, however, says the Congress has had to fall back on Nath because it has no other leader left to project. “The people of Madhya Pradesh remember the misrule during the 15 months that Nath was chief minister,” said state BJP president V.D. Sharma. “He stopped so many welfare schemes that were being implemented by our government.”

For Nath, who was seen as an outsider in state politics, this election marks a complete integration with the Madhya Pradesh milieu. The leader, who belongs to a business family, was born in Kanpur and brought up in Kolkata. He went to the prestigious Doon School and St Xavier’s College in Kolkata. He switched from business to politics over four decades ago. In the beginning, it was just about helping out friend Sanjay Gandhi during the turbulent 1970s. He soon became more closely involved with the party and joined the Youth Congress. In 1979, when Lok Sabha elections were announced, the party leadership asked him to contest. Indira Gandhi came for his nomination submission.

He won from Chhindwara in 1980 and did so eight more times. He also played a crucial role in the downfall of the Morarji Desai government by exploiting the internal problems in the Janata Party. Indira did not forget this, and she introduced him to the people of Chhindwara as her “third son”.

Chhindwara is Nath’s fortress; it was his connection to Madhya Pradesh even as he held important positions at the national level. Nath has nurtured Chhindwara and knows the lay of the land like the back of his hand.

There is an anecdote about BJP leader Prahlad Patel contesting against Nath from Chhindwara in the 2004 Lok Sabha polls. Patel had taken out a rally of jeeps and motorcycles as a show of strength. Nath responded by asking a mutual acquaintance to tell Patel that there was not a single jeep owner in the constituency whom he did not know. Patel lost to Nath by a huge margin, and when the message was finally relayed to him, he said, “Yes, he is absolutely right.”

Also read

- MP elections: Clashes in Dimani segment; Scindia says not in the race for CM post

- 'We are not playing any hindutva card': Kamal Nath

- How BJP is trying to overcome 'Chouhan fatigue' in Madhya Pradesh

- 'Our target is to win more than 150 seats': MP BJP chief V.D. Sharma

- Congress going the saffron way to win MP, Chhattisgarh, Rajasthan

Nath has the reputation of being extremely sharp, very particular about time management and strictly no-nonsense. He works long hours, and once, when asked about what time he wakes up, he said, “You should ask me what time I sleep.” Unlike the homes and offices of other politicians, there are no hangers on; not because he does not get visitors, but because he ensures his office deals with the people in a very efficient manner. However, it is said that the desire to run a tight ship could make him appear forbidding and aloof.

When Nath was made state unit president in 2018, he was identified more with the party high command than with people in his state. He was seen as an urbane, super-rich politician who did not have an understanding of grassroots-level politics. Some state leaders said this was his handicap in the 15 months he was chief minister; he did not have the required rapport and connect with the legislators or the party workers to prevent the exodus.

“When his government fell in 2020, Nath, it was felt, would move back to national politics,” said journalist and political expert Rasheed Kidwai. “But he did not. He proved the naysayers wrong by staying on. He took upon himself the task of retrieving lost ground.”

Nath got more involved in the nitty-gritty of state politics, from extensively touring the state to meeting leaders and workers. But there are sections in the party that feel that he still falls short in his connection with workers.

This gap, say his detractors, was visible in the protests and sloganeering outside his Bhopal house after the candidates’ lists were declared. It is felt that tickets ought to be given on the basis of feedback that one gets directly from the ground, based on one’s connect with the grassroots-level leaders and workers, and the process cannot be outsourced to agencies. However, Nath’s supporters say the tickets have been given on the basis of a very scientific selection process, based on multiple surveys. Nath, they say, has made an effort to deal with the disquiet over ticket distribution by reaching out to disgruntled leaders.

An important aspect of Nath’s politics in Madhya Pradesh is his association with another party veteran, Digvijaya Singh. They are known as the ‘Ram Lakshman’ of Madhya Pradesh politics, but there have been occasions when all has not seemed well between them. An example is the recent controversy over Nath’s “tearing of clothes” statement―he apparently told people coming with complaints from Digvijaya’s area to go and rip his clothes to vent their anger.

However, the two have stood beside each other at crucial junctures in their political career and continue to work in tandem. In 1993, Nath had helped Digvijaya overcome the claims on the chief minister’s chair by Shyama Charan Shukla. In 2018, Digvijaya sided with Nath when the party high command had to decide between him and Scindia for the top post in Madhya Pradesh.

Nath wielded significant influence in the state when Digvijaya was chief minister. And Digvijaya was seen as the power behind the throne when Nath became chief minister. Digvijaya, it is believed, has had to take a back seat in state politics because he is a prime target of the BJP and the RSS, which have labelled him ‘anti-Hindu’. He continues to work in collaboration with Nath in organisational matters and electoral strategy, and he is said to be building the ground for his son, Jaivardhan, to emerge as the next leader in the state.

Nath, on the other hand, has worn his Hinduness on his sleeve. He has often reacted to the charge of practising soft-hindutva by asking, “Kya BJP ne hindutva ka theka le rakha hai? (Can only the BJP practise hindutva?)”

He proudly declares himself a devotee of Lord Hanuman and has built a 101-foot statue of the deity in Chhindwara. He courted controversy when he hosted Dhirendra Shastri, the 27-year-old head priest of the Bageshwar Dham, at a religious event in Chhindwara, and appeared to be in sync with Shastri’s views on a Hindu Rashtra.

Nath’s critics say that his aggressive pursuit of faith could backfire. “The Congress is contesting this election on a communal plank,” said Aslam Sher Khan, hockey player-turned politician who has represented the Congress in the Lok Sabha and has been a Union minister. “This is the first time the party is carrying out such an experiment, where it wants to project itself as a better Hindu compared with the BJP. This could result in alienation of the Muslim voter.”

Nath is not affected by the criticism. He will do all it takes to win Madhya Pradesh.