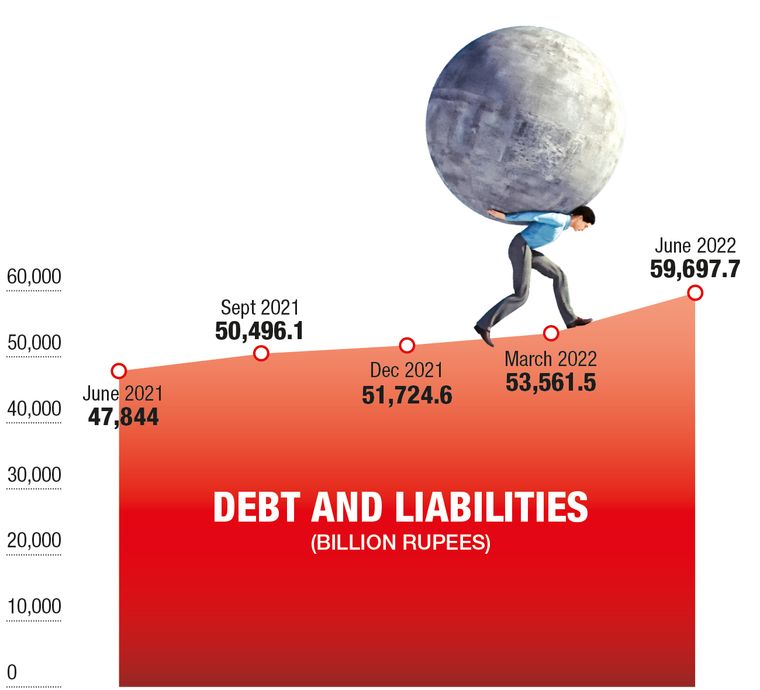

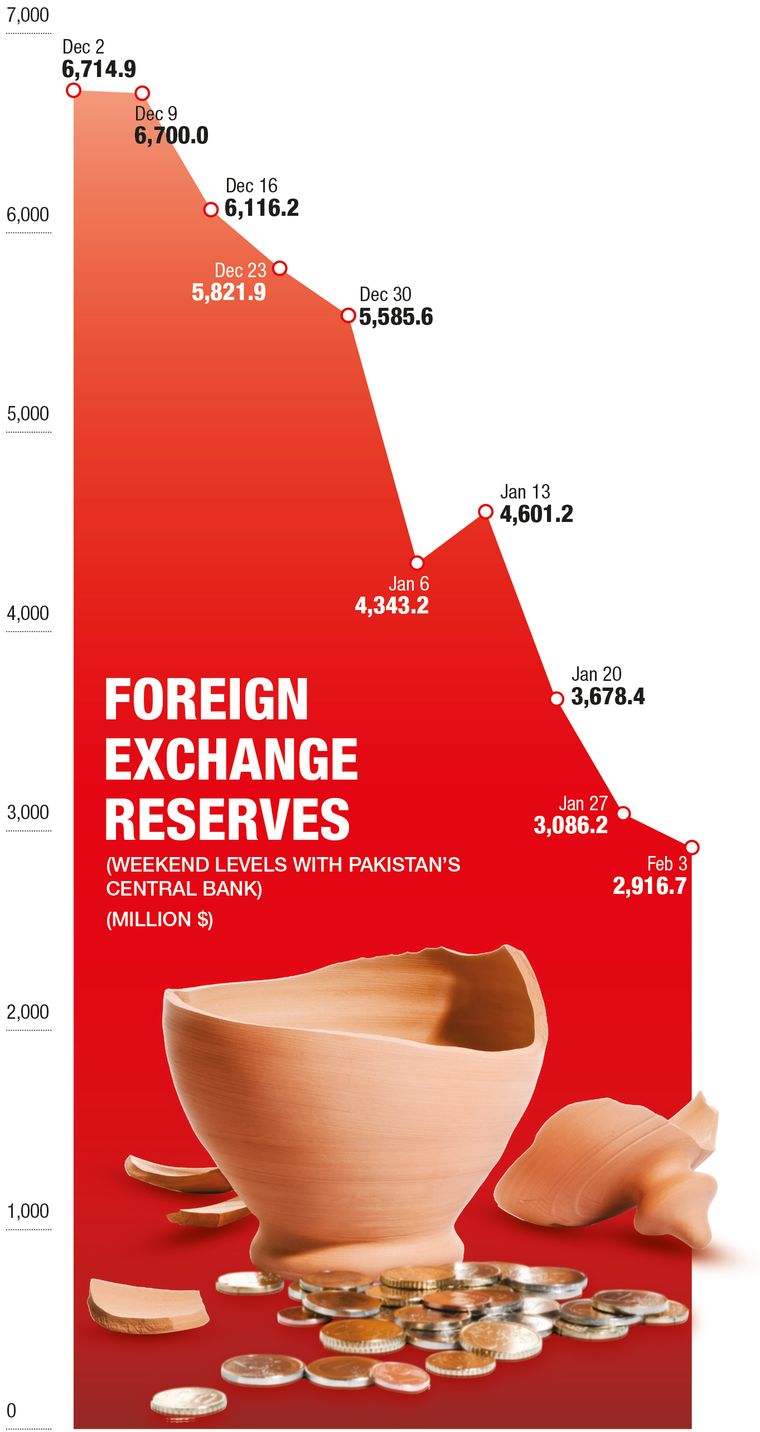

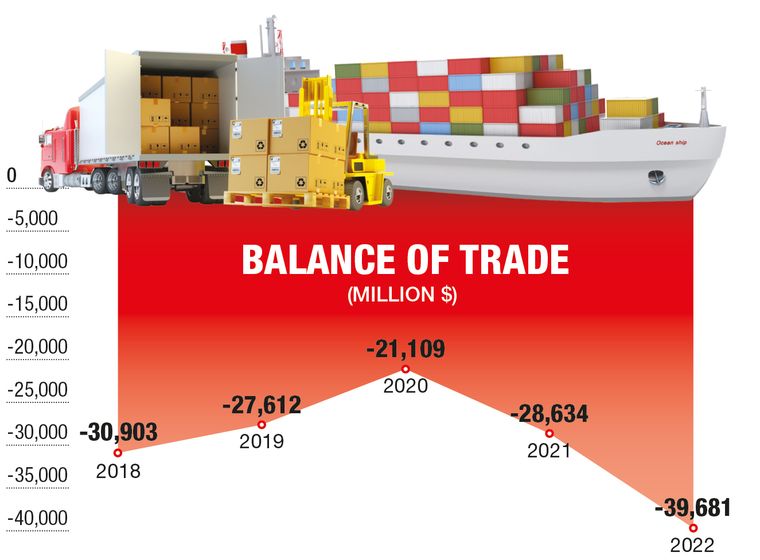

Without serious reforms, such as tackling the bleeding public sector enterprises and cutting the privileges enjoyed by the elite, Pakistan will continue to be in serious trouble. The International Monetary Fund is expected to sign off on yet another bailout package. This may provide temporary reprieve for the dollar-starved economy, but only for a few months. Within the next one year, Pakistan has to service its external debt to the tune of $22 billion. Exports are not increasing, while imports are inelastic, thereby leading to a perennial shortfall of foreign exchange, pushing the country into a debt trap.

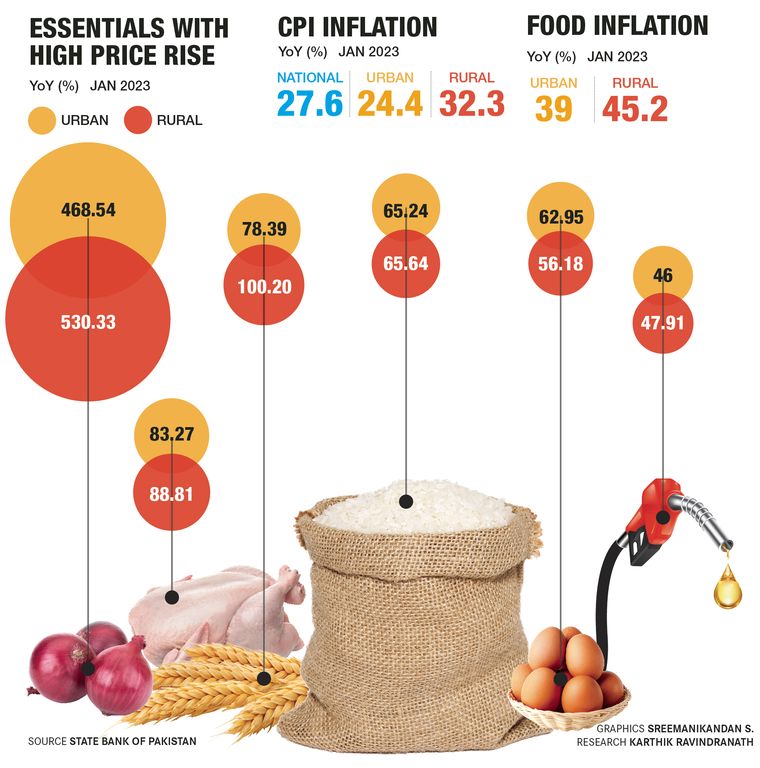

Pakistan's dependence on western aid since the 1950s acted as an elixir for its elites, particularly the military, the political class and corporate industrialists, who could conveniently delay the restructuring of the taxation system, redistributive measures and, more importantly, investing in education, science and innovation to create an export-led economy. With the exit of the United States from Afghanistan, and no immediate security imperative of the west, Pakistan's spoilt elites have been left high and dry. But the problem is not so much linked to the lack of western patronage, but the brazen inability of the ruling classes to give up their privileges, or, God-forbid, tax themselves. A recent study by the United Nations Development Programme estimated, obviously on the conservative side, that the elite privileges―if quantified―were worth at least $17 billion per annum. This figure includes the real estate barons, the pampered industrial sector and the military's corporate holdings, among others. The IMF is not asking for anything radical; all it asks for is expanding the tax net and reducing the budget deficit. In the past, when faced with similar demands, the standard policy response by successive Pakistani governments has been to levy more indirect taxes and pass the burden onto the general public, particularly the poor and the fixed income groups. That has been a standard playbook of increasing revenues, but the shelf life of this strategy is quickly approaching its expiry date as the political cost of transferring the burden to the citizenry has become untenable. If anything, the current government fears that increased energy prices and reduction of subsidies may result in political upheavals. Within the next few weeks, or perhaps days, the energy prices are going to soar and a new set of taxes―more than Rs170 billion―will be imposed. The rupee has already been devalued. The net devaluation in recent months has been more than 30 per cent. The biggest driver of inflation in Pakistan is the value of the US dollar, as it impacts the transportation of goods and services, imports that the manufacturing sector relies upon and basic necessities such as cooking oil and tea. The irony is that Pakistan's exported goods themselves use imported raw materials. Therefore, a 1 per cent devaluation has a multiplier effect. The inflation rate in Pakistan today is officially 25 per cent and, with the new measures, it is likely to cross 30 per cent.

The IMF programmes could lead to phases of stagflation in the short-to-medium terms, and this is the likely trajectory that Pakistan may face, given that there is no western cash assistance in sight. The solutions are well known: restructure the taxation system, mobilise domestic and foreign investment and undertake reforms in the energy sector that is a major source of the ballooning debt burden. The other two solutions are simple, but require long term political settlements: privatising the sick, bloated public sector enterprises that gobble up the biggest chunk of revenues, and rationalise defence expenditure. While these may appear to be unachievable at this stage, the country is moving towards that direction as its current expenditure levels are unsustainable. Undertaking major reforms and restructuring wasteful expenditures require at least a decade-long policy agenda that is adopted by all political players, including the military. At present, this is virtually impossible. The big political players―the ruling alliance led by Prime Minister Shehbaz Sharif and the opposition under former prime minister Imran Khan―are desperate to politically eliminate each other. The military has lost quite a bit of ground at the hands of Imran who is unwilling to forgive them for not saving his government.

Pakistanis are worried and for the right reasons. Hyperinflation, low growth, and rising unemployment paint a grim scenario at least in the short term. But this does not mean that the country cannot rescue itself. First and foremost, Pakistan's diaspora is a force to reckon with. It already sends $30 billion each year through official channels that keeps the economy and households afloat. Another $15 billion comes via unofficial channels, but there is much more than just hard cash that the diaspora can help with. Their immense expertise, technological prowess, knowledge and investment need to be leveraged and harnessed. Imran tried to do that, but such connections do not work in unstable environment and divisive politics do not inspire the kind of confidence expat investors need. The other low-hanging fruit is regional trade that, once again, requires a policy consensus. Economists have estimated that there is potential for trade worth $30 billion between India and Pakistan. There is hardly any trade with Bangladesh, the plans of importing cheap energy from Iran never materialised and trade cooperation with Russia is still in the embryonic stages. It requires firm and visionary leadership in Pakistan that can rally the civil society, the political parties and the media to open up trade with India and Iran.

Where the state faltered in providing education at different levels, a vibrant private sector has struggled to fill the void. Nearly half of all school-going kids in the most populous Punjab province attend private schools. Private universities and medical colleges are providing state-of-the-art education and train thousands of young professionals. This is where the state, as a regulator and facilitator, can play its role in not just ensuring quality, but also synchronising the skills imparted to students with the requirements of industries at home and abroad. Given its demographic transformation and leadership in a state of flux, Pakistan is a transitional polity. All its major leaders are on the verge of retirement, more than 60 per cent of its population is under 30, and there is a multitude of social movements―by the youth, women, transgender and ethnic minority communities―calling for a shift in the way the country is being governed. The traditional military and political elites are finding it difficult to stem this tide, and that is one reason why, to an outsider, Pakistan's situation seems so chaotic. Like all countries in transition, this will not be an easy and tension-free process. It will take many a systemic shock in the coming months and years, before there is a reset of the direction that Pakistan is headed in.

―Rumi is a Pakistani writer and public policy specialist who serves as director, Park Center for Independent Media, Ithaca College, New York.