She lay in beauty at the Kochi harbour like a bride, basking in glory. India’s first indigenous aircraft carrier, she has been the toast of the nation and the talk of the town. Kochi has been her home since February 2009, when the keel was laid at Cochin Shipyard Ltd. She will be called INS Vikrant and commissioned into the Indian Navy this month.

Two weeks ago, on July 28, after many successful sea trials, the shipyard handed over to the Navy the largest warship built in India. The mood at the shipyard, the biggest shipbuilding and maintenance facility in India, is buoyant, with men in red and navy blue putting the finishing touches to the aircraft carrier. It is a moment of pride, yet a poignant reminder: thirteen years have passed quickly and the shipyard’s ‘daughter’ will now be ‘married’ to the Indian Navy.

I asked Madhu Nair, the shipyard’s chairman and managing director, how the ‘father of the bride’ felt a few days before the ‘wedding’. He said, looking pleased with himself: “You should have seen the euphoria when she went for her first sea trial.”

The last six years were the most exciting and challenging, too. “Not just the shipyard, the Navy, various stakeholders within the system, came together,” he said. “Yes, there were technological challenges and inter-organisational issues to be sorted out.”

After all, 550 companies—big and small—were involved. Among them were 100 micro, small and medium enterprisess, each having its own work culture and methodology. “We had to iron out so many grey areas,” said Nair. “The kind of project management and networking we did, helped us to improve the speed.”

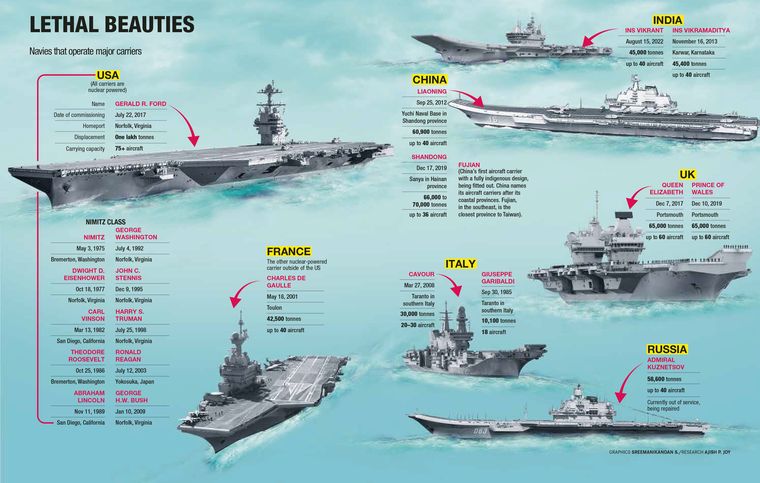

The size and scale of an aircraft carrier being mammoth, the learnings from building Vikrant are immense. “It is going to help us in future,” said Nair. “Earlier, people used to ask whether we had the capability to build a ship of such magnitude. Today, there are only five or six countries that can build an aircraft carrier, and India is one among them. The world has the confidence in us today.”

Over the years, Nair has played a pivotal role in building technology partnerships and bagging international contracts. Nair, who is from the temple town of Guruvayur, is a postgraduate in naval architecture and ocean engineering from Osaka University. He trained at IHI Kure Shipyard, which is Japan’s most modern shipbuilding facility. He joined Cochin Shipyard as an executive trainee in 1988 and became its chairman in 2016. Under him, it became a publicly listed company, raising Rs1,468 crore in an IPO. The Union government holds 73 per cent of its stake.

It was exhilarating as I walked on the top deck of the majestic Vikrant. Built at Rs20,000 crore, it is 262 metres long and 62 metres wide, and displaces 45,000 tonnes. Inside the ship, it was business as usual. It has 15 decks, a multi-speciality hospital, a pool, a kitchen and exclusive cabins for women. And, of course, the technology for carrying, arming and recovering fighter aircraft.

The statistics are mind-boggling: the ship has 2,300 compartments, and 2,400km of cables have gone into its making. It has eight gigantic power generators, and can generate four lakh litres of water every day. I saw Naval officers checking the equipment, inspecting a MiG-29 fighter and a Kamov-31 helicopter on the maintenance deck. In every part of the ship, officials of the shipyard and the Navy were working in tandem. “We would need a sheet to cover a marking behind the helicopter. Could you please provide it today?” asked a Navy official. K. Pradeep, additional general manager of the shipyard, responded equally politely: “It will be done at the earliest. Please let me know in case you need any more assistance.”

Structural demonstrations have been done. But there is still more to do—operationally, Vikrant has to demonstrate its functionality, which may take some months. Prime Minister Narendra Modi is expected to commission the ship this month end, and it will most likely be deployed in the western sea.

“After commissioning she would need four or five months more of trials with all the equipment and aircraft on board. This is the prerequisite for the carrier to be deployed as [part of a] mainstream fleet of the Navy,” said an officer.

Pradeep said the first sea trial had a festival-like atmosphere, with 1,700 people from the shipyard and the Navy on board. “I was also there,” he said. “We went 200km into the sea. The ship’s kitchen served food to everyone on board. We checked even minor things like whether the machines could make 1,000 chapatis and idlis in an hour on the sea.”

But, shouldn’t the delivery of the ship have happened a while ago? “In 2007, we had roughly set 2020 as the deadline. If not for Covid-19, we would have delivered it on time,” said Nair.

He recalled a snatch of conversation from 2014. Nair was present when Arun Jaitley, who was defence minister, asked his chief of naval staff about Vikrant’s progress. “A presentation was made. After a couple of slides, Jaitley said: ‘Tell me, Chief, how other countries fare in time and cost perspective.’ The chief said they took 10 years. Jaitley asked how much time India was taking. ‘Around 13 years, Sir,’ said the chief.

“Jaitley closed his eyes for a while and asked what was the cost of building an aircraft carrier abroad. ‘Around five and a half billion dollars,’ said the chief. Jaitley asked: ‘How about India’s?’ The chief said, ‘Three billion dollars.’ Jaitley thought for a while and then said: ‘Isn’t it all about India then?’”

“When someone with a lot of pedigree and expertise in warship building takes 10 years, we take 13 years,” said Nair. “Cost-wise also there is not much of a difference. We have shown what Indian industry is capable of.”

Nair said Vikrant was originally schemed as an air defence ship. “As we moved into the project it was changed into an aircraft carrier. We went purely by the Navy’s vision. The size and scale that the Navy wanted were given to them,” he said.

The shipyard has commissioned a Rs1,800 crore dry dock spread over 15 acres, in another part of Kochi, which can construct bigger aircraft carriers. “Like the US carriers that can carry many more aircraft. The new dock in Kochi will have the capacity to carry 7,000 tonnes of weight per metre. The Navy, in Vikrant’s case, wanted a mid-size aircraft carrier. The monstrous size that the US Navy wants is different,” said Nair.

Vikrant’s flight deck will be STOBAR (Short Take-Off But Arrested Recovery) configuration with a ski-jump, which will give aircraft extra lift during take-off. The arrestor wires on the flight deck catch the tail hook and bring the plane to a stop. If the pilot misses all three wires, he has to make another attempt at landing.

“The US Navy uses catapult more, to launch aircraft from ships,” said Nair. “STOBAR and catapult are two different philosophies. The Indian Navy is keen on STOBAR. Both have their advantages and disadvantages. Electromagnetic catapult works well on some aircraft. It depends on the planes we use. If we have to use heavy planes, we need catapult, as we move forward. There are geopolitical reasons associated with it. The power you have to put on the ship is decided by various factors.”

With 76 per cent of its constituents being indigenous, Vikrant is an example in the pursuit of Aatmanirbhar Bharat. “Probably, we can increase it to 85 per cent when we build the next aircraft carrier,” said Nair. “I wouldn’t argue that it has to be 100 per cent Indian. We are global. If there are certain things that are strategically blocked, then it is fine. When Russia blocked us steel [back in 2005], it set us back by two years. But, then, we developed that steel. Today, looking back, we are happy, because all the steel required for all warships is Indian.”

The steel was developed by Defence Research and Development Organisation, and initially produced by Steel Authority of India Ltd. It is produced by the Jindal Group and the SR Group today. Electrolytes were derived from Midhani. “What we have built is the best steel,” said Nair.

Cochin Shipyard, he said, can construct another aircraft carrier in a shorter time. It is ready to build INS Vishal, a second indigenous aircraft carrier, once the permission is granted. “It is being discussed at various levels. With the kind of expertise we have, the confidence we have gained, if the country desires it, and with the new dock, we will be ready for it,” said Nair. “We can make even bigger carriers and deliver them in shorter time, maybe in seven to eight years. But it is a decision that the Navy has to take. We are ready.”

The Navy has to decide how many carriers it needs. “Russians have moved forward with submarines. Americans want to move ahead with aircraft carriers. China does both,” Nair said. But, aren’t aircraft carriers sitting ducks? “We need aircraft carriers to establish our presence far away from our country. Islands cannot do that,” he said. “Aircraft carriers can take multiple hits and still survive. It can still perform. When one part stops functioning, the other parts do. No missile can damage Vikrant just like that.”

Vikrant is powered by four gas turbines totalling 88 megawatt power, and can last half a century. “Even on the first sortie we could go on full power,” said Nair. This is the first time that any warship in India could do that. You see, confidence shows. All helicopters of the Indian Navy landed on it.”

Also read

- INS Vikrant docks at Karwar base, Navy calls it 'landmark'

- INS Vikrant proof of India's skill and talent: PM Modi

- PM Modi to commission home-made aircraft carrier Vikrant today

- How an aircraft carrier projects power deep into the coast

- Need three aircraft carriers: Vice Admiral M.A. Hampiholi

- Aircraft carriers will deter China: Vice Admiral R.P. Suthan (Retd)

Shipbuilding technology after World War II moved to Japan, which is one of the three leading shipbuilding nations in the world today—after China and South Korea. “When it comes to technology and engineering, Europe is way ahead. But Europe may not be able to build large ships at the moment,” said Nair. “India can handle any type of defence ships. If we take a niche, size and scale, we have limitations. What is large in India is mid-size elsewhere. In our new dock, we can build even a two-lakh-tonne vessel. But, we don’t have to aspire to size. We should go for technology-oriented mid-size vessels for which there is a market.”

In the last three decades Cochin Shipyard has worked on INS Viraat and INS Vikramaditya, performing major overhauls on them. Yet, Nair felt there should be more awareness about shipbuilding in India. “Vikrant is helping in that direction,” he said. “In Norway, from every street you can see different ships and vessels. People are so used to them. Here, in India, our ports and shipyards are away from the cities, and there is limited access. Hence, people are not used to shipbuilding. In fact, many in India do not know about the difference between a port trust and a shipyard.”

Kochi has come a long way from 1928, when a modern ship entered its waters for the first time. It was SS Padma, built by Bombay Steam Navigation Company, the first Indian owned shipping company. Cochin Shipyard came into existence in 1972 and is celebrating its 50th year. It built its first ship, Rani Padmini, in 1981. More than 100 ships followed. Many of them were built for clients in the US, the UAE and Europe.

Nair clearly has a great sales pitch. Money cannot buy hearts, he said as I said farewell. “Today, every employee at Cochin Shipyard feels good that they have done something for society, for the nation. There is constant energy-churning here,” he said. “Vikrant has elevated all of us and made us better human beings. We will continue to work hard and serve the country to the best of our ability.”