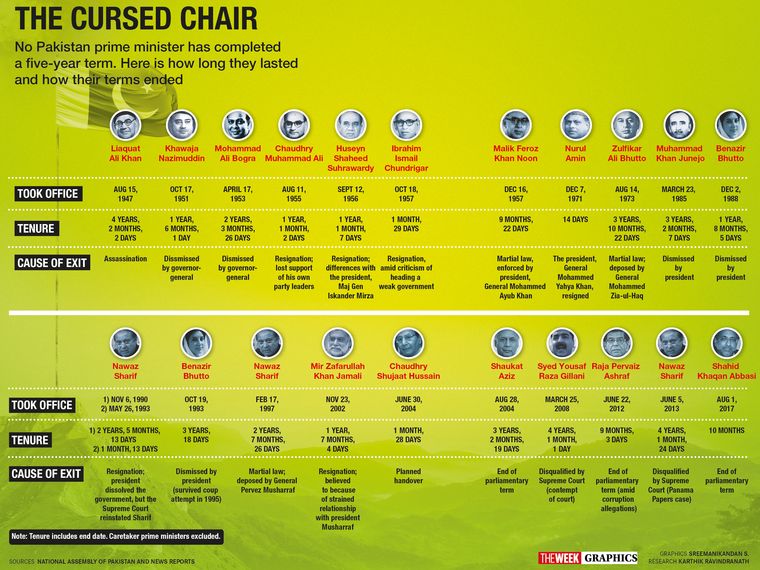

History in Pakistan is never the past. It looms large and is on loop. No prime minister has ever completed a five-year term. No prime minister has ever lost the no-confidence motion either. Only two faced it—Benazir Bhutto and Shaukat Aziz. Imran Khan became the first to duck the motion.

The slow month of fasting in Pakistan began with a bang as Khan dissolved the national assembly before the vote, in which the numbers were against him. Khan threw a googly, claiming that the motion was “foreign inspired” and “foreign funded”, and Pakistan slipped into a constitutional crisis.

Pakistanis now look to the Supreme Court for relief; the opposition has termed this a civilian coup. The only certainty is uncertainty. Early elections have been called by President Arif Alvi, in 90 days. A news report suggests that the Election Commission of Pakistan has expressed its inability to conduct elections at short notice.

“In a way, Imran Khan has played out the script that the military’s favourites always fall out,” said T.C.A. Raghavan, former high commissioner to Pakistan. “No one had expected this alliance to end this way.” The hybrid system has failed. Khan often said that his government was on the same page as the military, especially when it came to India. That is now officially over.

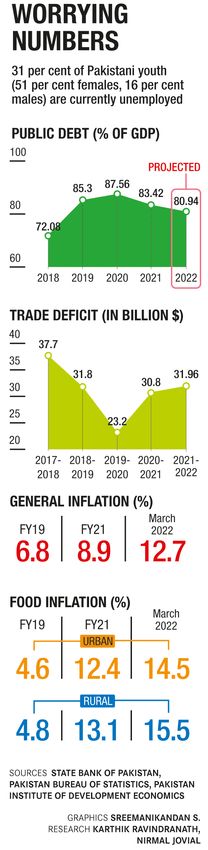

This is not the first time that Pakistan finds itself in the midst of a domestic crisis. Nor is it the first time that the Supreme Court has found itself arbitrating over a legislative issue, but it comes at a time when the economy is far from robust. “There’s a perfect storm playing out in Pakistan right now,” said Michael Kugelman, deputy director, Asia Programme, at the Wilson Centre. “There is political uncertainty and a worsening economy.”

With Sri Lanka still amid an economic crisis, another fragile economy in the region is cause for concern. The economy is projected to grow at 4 per cent, but in January, the Pakistan Bureau of Statistics put the consumer price index inflation at 13 per cent—the highest in two years.

Khan may have not created the economic crisis, but he has certainly contributed to it. Khan inherited an economy that had been mismanaged. “But they didn’t take the policy route,’’ said Haris Gazdar, an economist. “They took a populist route. They built a powerful narrative of corruption being responsible for the economic malaise, which has not been supported by the history of economics.”

At the heart of the change in dynamic between Khan and Chief of Army Staff Qamar Javed Bajwa is the numbers. “In Pakistan, there is a big penalty for economic mismanagement,’’ said Gazdar. The people in power are sensitive of their image and Bajwa is due to retire in November. This is the most important piece of the Pakistan stability puzzle.

“The military isn’t a monolith in Pakistan,” said Kugelman. “Khan’s relationship with the army chief may be shattered and several other top military leaders may have been turned off by his relentless anti-US and anti-west rhetoric. But, there’s no reason to think he’s lost the institution on the whole. He continues to have close ties with several key military leaders, including the previous ISI director who could be in the running to become the next army chief, if Khan finds himself back in power when Bajwa’s term ends in November.” He added that while the military did not do anything to prevent the opposition from bringing forward its no-confidence vote, it also did not stop Khan from dissolving the assembly. “And that is telling,” he said.

But, Khan has added to the fragility of Pakistan politics. Over the past four years, he has been unable to reach across the aisle to forge alliances. Khan has attended only around 10 per cent of the sessions—an indication of the low emphasis he placed on the process. With a wafer-thin majority and Khan’s crusade on corruption, which put major leaders behind bars, the parliamentary process has suffered.

Dissolving the assembly has added to the political chaos as it has left the Supreme Court dealing with a constitutional pickle. Whether the court will be able to stand up and prove its impartiality remains to be seen. Khan has also chosen to add a “foreign hand’’ conspiracy to this mix. He named the US’s Donald Lu, an assistant secretary of state, for threatening the Pakistan Ambassador Asad Majeed Khan with consequences if Khan survived the no-trust vote. The US chargé d’affaires in Pakistan was issued a late-night demarche. But, again, Khan is not the first leader to use the anti-American sentiment to his advantage.

Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto made the same allegation in 1977, when he claimed that the demonstrations spread across the country were being funded by the Americans. It is no secret that the relations between the countries have not been at their best. Khan had waited for President Joe Biden to make a call, which never came.

“The relations with the US had stalled for some time now,’’ said former Pakistan foreign secretary Salman Bashir. “It goes back to the last few months of the Obama administration. There were differences of perception. After [2021] August (Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan), I can imagine that there are issues germane to US politics that blame Pakistan for what happened.”

At the Islamabad Security Dialogue, Bajwa chose to defuse tensions and batted for Pakistan emerging as an economic melting pot, stressing on connectivity and friendship, especially within the region. “Pakistan does not believe in camp politics and our bilateral relations with our partners are not at the expense of our relationships with other countries,” he asserted, in reference to Islamabad’s close ties with China. Referring to relations with the US as “long and excellent’’, he said that Pakistan sought to broaden and expand relations with both China and the US “without impacting our relations with [either]”.

Khan is hoping that the anti-American sentiment will translate into votes. It is a narrative that will play to the heart of his voter: Pakistan is no longer a lackey of the west. It will resonate with the young Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf voters who passionately buy into the idea of the naya (new) Pakistan that is mukt (free) of corrupt opposition.

Will this have an impact on US-Pakistan relations? “There’s no denying that a blow has been dealt to US-Pakistan relations,’’ said Kugelman. “Khan has accused the US government, with no evidence, of trying to overthrow him. There’s no way they can just shrug off something like that. That said, let’s not overstate the damage to the relationship. Also, the military-to-military dimension of the relationship is unlikely to be impacted, and Bajwa’s conciliatory words make clear that he’s keen to continue cooperation with his counterparts in the US. That said, the future of US-Pakistan relations will be determined to a great extent by the next Pakistani government. If Khan returns to power, it’ll be a lot tougher to make things work.”

Also read

- Masterstroke or civilian coup? Imran Khan’s move divides Pakistan

- Imran Khan being punished for standing up for Pakistan: Former aide

- How Imran Khan transformed from Pak army's yes-man into a rebel

- Why Pakistan wants peace with India

- Shehbaz Sharif, the top choice to replace Imran, steps out of his brother’s shadow

It is yet to be seen whether his anti-US rhetoric will finally galvanise votes, but it certainly has managed to win friends eager to egg him on. Russia, of course, and China. “It will naturally make China very happy,’’ said Ayesha Siddiqa, a military expert and political commentator. While China may not be willing to do the heavy economic lifting for Pakistan, having extra leverage will certainly help. “The military leadership, especially Bajwa, do not want to be Sri Lanka and the balancing relationship will not be easy,” said Siddiqa. India may not choose to deal with Pakistan, but a stronger China in the region is not likely to make South Block happy.

Despite the uncertainty in Pakistan, it is clear that Khan will not be beaten easily. “Khan has always been a smart politician,’’ said Kugelman. “Critics’ claims that he’s dim-witted have always been wildly off the mark. You can’t become prime minister in a country with such a brutal political scene without having smarts. What he did may well be unconstitutional and therefore undemocratic, but it was also, on some levels, a stroke of genius. He denied the opposition, energised his rank and file, and strengthened his position ahead of early elections.”

The last ball is yet to be bowled.