17 September 2009. A day I shall never forget. It was four in the afternoon when I was standing at a bus stop below Bhikaji Cama Place in Delhi. I had gone to the bustling business district with a friend to purchase computer material. I was waiting at the bus stop for a few minutes when a SUV pulled up and about half a dozen toughs pounced on me, pushing me to the ground as I struggled to free myself. They seized everything on me, dragged me into their car and sped away.

Little did I know that this marked the beginning of a ten year-long journey, as an undertrial, through seven jails in five states across the country. I was sixty-two years old and had come to Delhi from Mumbai for urgent medical attention, for a serious prostrate/urinary problem, as well as orthopaedic and hypertension issues. The abduction was in fact an arrest. The charge? That I was a member of the banned Communist Party of India (Maoist), with the media widely propagating that I was supposedly one of its top leaders…. What then is this ‘dangerous’ party, of which merely being a member invites a life sentence, and even bail is not possible?... Inside the car they were speaking Telugu amongst themselves, while one questioned me in broken Hindi…. The word ‘airport’, though, kept cropping up. The Andhra Pradesh Intelligence Bureau (IB) were known to fly people in helicopters to jungles in their state and bump them off, and report that they’d been ‘killed in encounter’. I assumed this was the end. But, at three in the morning, we reached a ‘safe house’ with high walls where I was finally allowed a few hours of sleep. The next morning, intelligence people from a number of states had gathered at the safe house but the main questioning was by the men from Andhra Pradesh. They claimed I was a politburo member of the CPI (Maoist) and wanted details of other members of the Central Committee and Politburo of the party—details which they seemed to already have; certainly more than what I knew. When they could not elicit any additional details from me, they used threats, but did no direct physical harm, probably given my age, and the fact that I was already ill and had just come from a hospital check-up. They were particularly keen on getting to the place I was staying in Delhi, in the working-class locality of Badarpur, where my friend Rajender Kumar (and later co-accused) had a rented accommodation, to get my computer and any other written ‘incriminating’material.

They tried all the standard techniques, stopping short of using physical force, to extract information from me; they’d raise the same questions again and again, quote others as having confessed, issue various threats and enticements of not putting cases, and so on. As the entire procedure was illegal (IB does not have the powers to arrest, I later learnt), they would not openly go to the room where I had been staying in Delhi though they tried to reach the room by other means.

By 20 September it appeared that news was leaked to the press that I had ‘disappeared’. I gathered this because in the morning there was a great flurry to urgently produce me before the Special Cell of the Delhi Police. On the way to the Special Cell office I was instructed to not mention that I had been picked up three days ago, and instead say it had just been a few hours. That afternoon, I was deposited at the first floor of the Special Cell office. There was a bit of black comedy to the whole situation, as this was the first time a ‘Naxalite’had been brought to their office. Having been used to Islamic terrorists, they knew little about what we creatures were.

*************

When I met Anu (Anuradha Shanbag) she was a student leader at Elphinstone College, and active in the Alternative University. The first time I saw her in class I saw an extremely bubbly and articulate student, raising questions, making points and being exceedingly communicative. I was very attracted to her naturalness, her spontaneity and liveliness…. At the time we met, Anu was in a relationship with a fellow student, a sportsperson who was not politically inclined and the relation ended sometime after her activities grew.

Injustice would trigger anger in her, she could get very annoyed, but it would not linger and she would move on. She never stood on ego or prestige nor did she hold grudges. And this was not an effort, it came naturally to her. My temperament and qualities were almost totally antithetical to hers. Soon after we met, she began working with me in Mayanagar and elsewhere in the city. In the early days, most of our time together meant meetings, lengthy study classes, or sitting at my Worli Sea Face flat making posters, with little time off. We would go out late at night to put up posters, and together with others sit at the Worli home to make the handwritten posters. At most, we’d see some plays together, many by her brother and Satyadev Dubey, mostly at the Chabbildas and Prithvi theatres. It was during the Emergency, when most activity came to a halt, that our love really blossomed and we got to meet more often and spend some time together.

*************

Indora (in Nagpur) was such a dreaded place that middle-class people were scared to go to that area after dark due to the impression that it was a nest of crime and were shocked to find we were living there. Such impressions are easily created in impoverished Dalit and Muslim localities because of inbuilt biases and a certain amount of petty theft due to extreme poverty that gets magnified.

A typical day in Nagpur would start with Anu cycling/ busing to university, over 15 kilometre away, leaving early in the morning after having breakfast. I would do some of the cleaning up of the rooms and then meet the Dalit members of the community in our basti.

Working amongst Dalits we hoped to arouse them not to accept their existing status that their religion sanctified. We encouraged them to stand up for their rights and study both Ambedkar and Marx. Ambedkar would give deeper insight into the caste issue, while Marxism would keep them away from identity politics and help them unite with other oppressed, even from other castes. The two ideologies would show them the path as to whom to target and whom to ally with—i.e. target Brahminism (the ideology) and those who propounded it and not all upper castes; on the contrary one needed to educate those from the other castes (like the OBCs and even upper castes) to drop their casteist feelings. We would encourage inter-caste love marriages to help facilitate this unity…. One had to counter identity politics amongst Dalits which the Dalit political leaders promoted for their vote-banks.

Many of the youth of Indora were attracted to our views and joined our organizations of student/youth, especially the cultural organization, Aavhan. Jyoti, the daughter of Khushal Chinchkhede (the postal employee whose first floor we rented), and her friend who stayed across the road, Jyotsna, were active in our organization.

In Nagpur, we used to travel all over the city on cycles in the notorious Vidarbha heat. Earlier our residence was reasonably near the university where Anu taught. Indora was virtually at the other end of the town. Her schedule was so hectic that only strict discipline, her high level of commitment to any task she took up, and her inexhaustible stamina enabled her to do justice to both her students and to her social activities…. Anuradha led by example, living the life she wanted the basti boys to lead.

*************

Soon after leaving her university job (Nagpur University), Anu went to Bastar and spent two years gaining much experience of life there and women’s issues amongst tribals…. Together with the other mahila (female) comrades, Anu helped to develop the women’s organization KAMS (Krantikari Adivasi Mahila Samgathan) in the area. KAMS is said to be the biggest women’s organization in the country with about 90,000 members and is, what Arundhati Roy calls, ‘probably one of India’s best kept secrets’….

Anu used to say those two years were the richest in her life…. [But] it was a tough two years, as life there is not easy, particularly for a 46-year-old with arthritis and yet to be diagnosed, systemic sclerosis.

************

When I entered the ward for the first time, it was past 7 p.m., so all the inmates were already locked up in their respective cells. As I was being taken to Block A, I was greeted by a warm smile from none other than Afzal Guru who, standing at the gate of his cell, said he was expecting I would be brought to this ward in Tihar after reading about my case splashed all over the newspapers.

He immediately offered any help as I was taken away by the guards to Cell No. 4, which already housed three inmates, including Delhi’s top don, the dreaded Kishan Pehalwan. They offered bedding and shared their dinner which they had not yet consumed. Of course, I was so shaken by the events that hunger and sleep both seemed distant. My first night in jail, with four of us cramped in a cell, was difficult to pass. The others in the cell were mostly criminals and we had nothing much to communicate with each other. Although each cell is meant to hold a single inmate, due to overcrowding, three inmates are often housed in a cell together—either one or three are allowed, never two.... Besides Afzal, there were many interesting persons like the Khalistanis, another don, and some Islamists….

Next morning, I was shifted to the last cell in the block of eight cells where my two fellow inmates were two Khalistanis (actually one was a smuggler of guns and drugs from across the border with Khalistani leanings). Even before being shifted to this cell, as soon as the gates opened, Afzal was there inviting me for tea in his cell; a routine that continued for over three years, till his hanging in February 2013. He had a knack of converting basically hot water into an excellent cup of tea. He had a half-litre white thermos flask (which I asked for as a memento after his hanging, but nothing was given) in which he filled the hot ‘tea’that came from the jail kitchen, to which he added milk powder and a few tea bags purchased from the canteen. We would have it with the two slices of bread (made in the jail bakery) provided by the jail…. As this was my first experience in an Indian jail, he was reassuring, helpful and mildly sympathetic to the cause of the oppressed people in India, unlike the Islamists, who saw no difference between the communist or other parties.

************

Afzal, though had strong faith in Islam—he did his namaz five times a day, observed a strict Ramzan, had a strong belief in the afterlife (Jannat), opposed idol worship and dargahs, had a mistrust of Shias—was not a fundamentalist. He was a Sufi and had done a detailed study of the six volumes of Rumi in Urdu. He showed a keen interest in socialism and would often quote Iqbal who he said once wrote: communism + God = Islam....

Afzal was well read, having studied people like Noam Chomsky and other anti-imperialists. He was the only person in jail fluent in English so we would talk in English or Hindi (he could speak but not read the latter)…. Afzal’s extensively detailed diary has not seen the light of day; probably burnt by now. In fact, none of his belongings were given to us, though we asked for them.

Excerpted with permission from Roli Books.

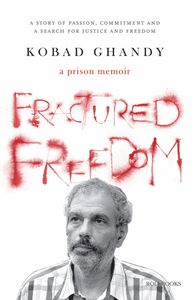

Fractured freedom: a prison memoir By Kobad Ghandy

Published by Roli books

Price Rs595; pages 316