On July 6, 2000, prime minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee arrived in Kolkata to inaugurate the birth centenary celebrations of Syama Prasad Mookerjee, his political mentor. Vajpayee was Mookerjee’s secretary when he was the president of the Bharatiya Jana Sangh. West Bengal chief minister Jyoti Basu, who had sanctioned the use of the Netaji indoor stadium for the celebrations, and deputy chief minister Buddhadeb Bhattacharjee were invited to the function. But Basu was away in Israel, and the state cabinet gave the event a miss. A furious Vajpayee later told journalists that the leftists had insulted Bengal by boycotting the event. But then Mookerjee’s politics had always been unacceptable to a large section of the Indian political establishment, especially the left, as they believed that he promoted communal politics.

Not all would, however, agree. Legendary communist and iconic parliamentarian Hiren Mukherjee wrote this in a tribute published by the parliament secretariat: “Mookerjee could not be glibly branded as a mere communalist, though in the heat of politics he often was. One could always discern the catholicity and, also within limitations, the rationality of his outlook. He cherished freedom of opinion and was far away from socialism, as one could be, but there was in him an innate liberalism. He made no bones about his Hindu Mahasabha links but he was a champion of civil liberties and kept himself above the narrowness of communal chauvinism.”

Mookerjee saw himself as the defender of Hindu rights, especially in his homeland—the Muslim-majority Bengal province of British India. He felt the Congress was not standing up to the Muslim League, especially during the frequent communal riots in Bengal. And he was a trenchant critic of Mahatma Gandhi’s version of secularism. Many Congress leaders agreed with him on the issue, but they stayed silent out of deference to Gandhi. Mookerjee, eventually, got slotted as a communal leader.

In 1952, when they both were members of the first Lok Sabha, Mookerjee jokingly told Hiren Mukherjee, “Do you know Hiren, they have allotted accommodation to me at Tughlak Crescent, mind you, not on Tughlak Road. And, I don’t bat an eyelid, yet some people call me a communal Hindu.”

FROM STUDIES TO STATECRAFT

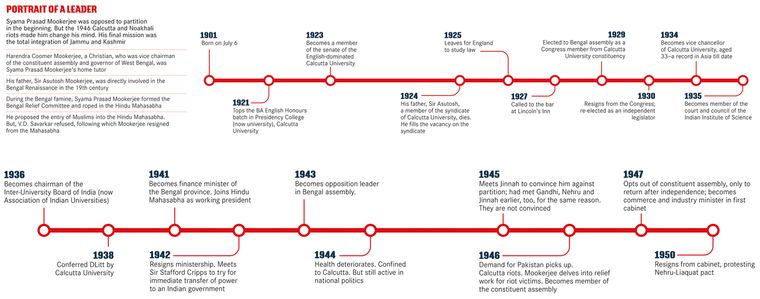

Mookerjee was born in 1901 into one of Calcutta’s most respected families. His father, Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, had served as vice chancellor of Calcutta University and as a judge of the Calcutta High Court. After completing his BA Honours in English from Presidency College, Mookerjee went on to pursue his master’s degree in Bengali language as he wanted to promote his mother tongue. In 1925, he left for England to study law and was called to the bar at Lincoln’s Inn in 1927. Upon his return to India, he turned his focus to higher education and, in 1934, was appointed vice chancellor of Calcutta University. He played a leadership role at several other prominent institutions such as the Asiatic Society and the Indian Institute of Science.

Throughout his career as an educationist, Mookerjee had never been influenced by religious considerations. His family members told THE WEEK that Muslim academics from all over the country used to visit him at his south Calcutta residence. Some came seeking his support to maintain their schools, colleges and students. “Legendary Bengali poet Kazi Nazrul Islam faced starvation at one point of time. It was Dr Mookerjee who saved his life,” said Anirban Ganguly, director of the Delhi-based Syama Prasad Mookerjee Foundation.

Mookerjee’s first brush with electoral politics came in 1929 when he was elected to the legislative assembly as a Congress candidate representing Calcutta University. He resigned a year later and got himself re-elected as an independent candidate after the Congress boycotted the assembly. Mookerjee became increasingly involved in politics after he was re-elected in the 1937 elections. He started associating himself with the Hindu Mahasabha, then headed by V.D. Savarkar.

The 1937 elections resulted in a coalition government of the Muslim League and the Krishak Praja Party, a breakaway faction of the League headed by prime minister A.K. Fazlul Haq. Two decisions of the Haq government pushed Mookerjee deeper into politics. He was opposed to the decision to reserve half of the seats in the Calcutta corporation council for Muslims. Although Muslims were in majority in the province, they constituted less than 30 per cent of the city’s population.

Mookerjee was even more appalled by the government’s plan to remove Calcutta University from the supervisory role over secondary education in Bengal and give it to a board nominated by the government. He felt that it was a deliberate attempt to communalise the education sector. Despite his opposition, the Haq government passed the corporation bill, reserving 46 of 93 seats in the corporation council for Muslims.

BATTLE WITH BOSE

After the corporation bill was passed, new elections were scheduled to be held in early 1940. Subhas Chandra Bose, who was forced to quit as Congress president at the 1939 Tripuri session of the All India Congress Committee because of his differences with Gandhi, saw the corporation elections as a platform to demonstrate his popular support. He had launched a pressure group called the Forward Bloc within the Congress; he proposed that the Bloc and the Mahasabha together fight the League in the corporation elections.

Bose and his elder brother Sarat, who then headed the Bengal Congress, discussed the alliance with Mookerjee. Although Mookerjee supported the proposal enthusiastically, negotiations broke down at the last minute. The Mahasabha fought alone and won 50 per cent of the seats. “We defeated Subhas’s force whom Gandhi followers had feared to challenge,” wrote Mookerjee in the book Leaves from a Diary.

Bose, however, allied with the League to keep Mookerjee at bay. Shocked, Mookerjee wrote: “The great liberator and leftist who regarded Gandhi, Jawaharlal and the rest as moderates, and branded them as ‘compromise-wallahs’, was not hesitant to install a League mayor and placate the League for his own purposes. He was out to wage a relentless war on the League ministry in one breath, in another he was a warm and dear ally of the League while it ruled the corporation. Could Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde do any better?”

Bose, too, was shaken. The electoral drubbing and the uncomfortable alliance led to his leaving Calcutta to focus on the Azad Hind and the Indian National Army. In 1941, he left his homeland for the last time, via Afghanistan.

Mookerjee, however, did not forgive Bose for what he felt was a betrayal of the Hindu cause. He accused Bose of being autocratic and even of committing financial irregularities, citing certain observations made by Congress leader B.C. Roy. “Dr Roy made an astounding statement that there have been serious financial irregularities on Subhas’s part,” wrote Mookerjee. “Monies received as purses presented to the president have mostly been appropriated by himself—while according to previous practice 75 per cent should have gone to provincial Congress funds and 25 per cent to the central fund.”

SETTING THE SYLLABUS RIGHT

The strong performance in the corporation election, however, established Mookerjee in Bengal politics. Soon, he became working president of the Mahasabha. In December 1941, when the Muslim League withdrew support to the Haq government, Mookerjee helped cobble together an alliance that propped up Haq and kept the League out. He became the finance minister in the new government. To this day, Mookerjee’s detractors cite this experiment to bolster the allegation that he got into bed with the Muslim League for the sake of power.

In March 1942, when the education bill was taken up by the cabinet for discussion, Mookerjee told governor John Herbert that it was being proposed because of political reasons. He said the secondary education board should not be in the hands of the proposed 18-member political committee, which would be dominated by Muslim bodies, but should be controlled by government officials. The government was forced to drop the bill because of Mookerjee’s opposition.

The bill was proposed again in 1944. By then, Mookerjee had resigned his ministership and Khwaja Nazimuddin of the League was the prime minister. He continued to oppose the bill and threatened that if it was passed, he would launch a movement demanding a separate secondary board for Hindus. After listening to Mookerjee’s arguments, governor Richard Casey asked the cabinet to consider whether the bill would lead to communal disturbances.

Nazimuddin thought the bill was important to checkmate Mookerjee and told the governor that his government had the support of the scheduled castes as well. “Dr Mookerjee would find it difficult to create any communal feeling. The teachers already have been attracted by the DA hike and would get substantial grants in improving schools,” said Nazimuddin, according to declassified cabinet documents. The governor, however, listened to Mookerjee’s objections and sent the bill to the director of public instruction. The government was ultimately forced to drop the bill.

SPARRING WITH SAVARKAR

Despite allegations that Mookerjee was a product of the Savarkar ideology, he was never a blind follower. Mookerjee had a mixed relationship with Savarkar. He was angry that Savarkar chose to ignore the Mahasabha’s decision to launch direct action if Britain failed to honour its promise of complete transfer of power. “I had joined Mahasabha in the full belief that I would not hesitate to fight the government at the right moment and thus pave the way ourselves towards national freedom,” wrote Mookerjee. He felt Savarkar had no desire to popularise the Mahasabha; he quit the party after Savarkar refused to initiate reform measures and give membership to liberal Muslims.

THE QUIT INDIA CONTROVERSY

Mookerjee’s critics maintain that he betrayed the Quit India movement by joining hands with the British. While he was initially opposed to the movement, declassified documents reveal that Mookerjee’s resignation from the provincial cabinet on November 20, 1942, was largely influenced by the brutal crackdown the British administration unleashed against Congress leaders.

In August 1942, governor Herbert informed the Bengal cabinet that viceroy Lord Linlithgow had declared the Congress an unlawful organisation and that there would be a stringent crackdown against the party. Haq said he agreed with the viceroy. Mookerjee was the only cabinet member to oppose the decision.

“It is essential to appeal both to people and British government through the viceroy. The attempt might fail but it would be a noble failure. And if the ministers fail, they might have to resign,” he said.

Mookerjee wanted to meet Gandhi in jail, but was denied permission. He wrote to the viceroy that the demand of self-rule by the Congress was a demand of all Indians. “What is regarded as the most unfortunate decision on the part of the British government was its refusal to negotiate with Mahatma Gandhi, even after he gave his emphatic assurance that the movement would not start until all avenues for an honourable settlement had been explored.”

In his letter, Mookerjee listed a series of conditions to be followed by the Indian national government if Britain granted independence to the country. One of the proposals was about the importance of guaranteeing minority rights. “There will be a treaty between Great Britain and India which will specially deal with minority rights,” he wrote. “In any case, any minority will have the right to refer any proposal regarding the future constitution to the arbitration of an international tribunal, in case it considers such a step to be necessary for the protection of its rights. The decision of such a tribunal will be binding on the Indian government and on the minority concerned.”

As the letter went unanswered, Mookerjee continued in office for only a few more months. A devastating cyclone hit Midnapore in early November, and Mookerjee felt that the relief and rescue efforts organised by the governor were inadequate. It was the last straw for him and he submitted his resignation on November 20.

FACE OFF WITH FAMINE

The dreadful famine, which devastated the Bengal province in 1943 and 1944, saw the death of more than 50 lakh people. Mookerjee had warned the cabinet in July 1942 that governor Herbert was misleading the viceroy about the food situation in Bengal. “Since the military is lifting huge amounts of resources, it would be required to send fresh statistics to the government of India,” he said, according to declassified files. Mookerjee strongly criticised the government’s decision to divert rice from Bengal to British troops in the Gulf and Ceylon.

After the governor denied the allegation, Mookerjee revealed that the decision was made by the concerned joint secretary in connivance with the Muslim League, without consulting the minister. “The joint secretary had without sufficient examination given the contract to an agent who had no organisation for doing the work and was effecting purchases at government expense through representatives of the Muslim League,” said Mookerjee. The Haq ministry was dismissed by the governor in March 1943 and a Muslim League government headed by Nazimuddin was appointed in its place. The new government constituted a civil supplies department to tackle the food crisis.

According to declassified papers, Bengal exported two lakh tonnes of rice in 1942, despite the threat posed by World War II. Madras and Bombay, the other two major provinces, had set up channels to purchase and distribute food. But Bengal kept on exporting its rice stocks. “Calcutta had a large European commercial community which controlled the distribution of rice. Rice was exported by Shaw Wallace & Co, which was meant for industrial workers. Export to the Gulf, too, continued unabated,” said the declassified files. Suhrawardy, meanwhile, kept open inter-district and inter-regional rice trade, despite opposition from Nazimuddin. Suhrawardy said the alarming situation in the rural areas forced him to keep trade channels open. But the government reserves ran out in no time. Suhrawardy then imposed fresh agriculture tax and also hiked sales tax, causing the prices to skyrocket, accentuating the effects of food shortage.

To deal with the crisis, Mookerjee set up an organisation called the Bengal Relief Committee. He also launched an agitation against the government’s inept handling of the crisis. Nazimuddin recognised what Mookerjee was doing; in an oblique criticism of Suhrawardy, he said that Mookerjee would have lost his face had the food ministry been able to show some result.

In December 1944, Suhrawardy himself admitted failure and acknowledged the good work done by Mookerjee. “Because the government failed to step in to control and coordinate the activities of relief work, the Bengal Relief Committee and the Hindu Mahasabha took the lead in the matter of relief and acquired a disproportionate amount of authority and prestige,” said Suhrawardy.

RIOTS MOST FOUL

Suhrawardy’s mischief was not just limited to the civil supplies department. Declassified files show that he played a leading role in instigating communal riots on August 16, 1946, which was observed as Direct Action Day by the Muslim League, demanding the creation of Pakistan. There was widespread rioting across Calcutta, Howrah and 24 Parganas, in which thousands of people lost their lives. The number of Hindu casualties was higher as Suhrawardy took control of the police control room at Lal Bazar and directed police action. Mookerjee requested governor Fredrick Burrows to deploy the army, but it was delayed because of Suhrawardy’s intervention, resulting in more death and destruction. With no official help forthcoming, Mookerjee organised defence and counterattack teams for Hindus with the support of the city’s Marwari groups. Communal riots broke out a few months later in Noakhali, located in present-day Bangladesh. The situation was so dire that Gandhi rushed to Noakhali to bring the situation under control. In his report to governor Burrows, Suhrawardy accepted that a large number of Hindus were forcibly converted. “They were being fed and looked after in their villages, but they were being kept there virtually as prisoners,” wrote Suhrawardy. Mookerjee, too, wrote to the governor, highlighting the violence and conversions and, for the first time, demanded the partition of Bengal to protect Hindu interests.

PANGS OF PARTITION

The seeds of Bengal’s partition were sown during the time of the great famine. But it was kept in check by Suhrawardy and Sarat Bose, who were working hard to keep the province united. Bose’s grand-niece Madhuri wrote in her book The Bose Brothers that Congress workers in Bengal were opposed to partition.

“In May 1947, the majority of Congressmen in Bengal remained in favour of a free and united Bengal. Those not in favour were influenced by the pro-partition propaganda largely financed by the Hindu Marwari capitalists of Calcutta, with Shyama Prasad Mukherjee of the Hindu Mahasabha as the main spokesman,” wrote Madhuri, quoting her father Amiya Nath Bose. Madhuri, a human rights lawyer based in Geneva, told THE WEEK that the Bose brothers—Sarat and Subhas—were Indian nationalists whereas Mookerjee was a Hindu nationalist. “The disagreements and conflicts that arose between them can be explained by this fundamental difference,” she said.

Madhuri said including Suhrawardy in the united Bengal movement possibly did hurt the cause. “But for Sarat, achieving his goal of keeping Bengal united was paramount and he was ready to reach out to those he believed shared this goal no matter what their personal interests were,” she said. Mookerjee, however, trumped both Sarat and Suhrawardy using his influence in Delhi with Jawaharlal Nehru and Vallabhbhai Patel. Both leaders wanted to retain Calcutta at any cost.

THE POLARISATION DEBATE

Mookerjee remained a deeply polarising figure throughout his political career. He was not a blind dogmatist, but he feared that his homeland was facing the threat of creeping Islamisation orchestrated by the Muslim League and facilitated by the British government. The demographics of Calcutta—a Hindu majority city located in a Muslim majority province—indeed affected and shaped his thinking. He fought against giving Muslims reservation and other concessions. He took strong exception to the fact that government departments often ignored merit and used religion as a criterion for recruitment. In 1943, the Bengal Public Service Commission published a report on recruitment practices in the province. It revealed that the home department, for instance, often recruited only Muslim candidates from the merit list given by the commission, ignoring higher-ranking Hindu candidates.

Even after India became independent, the ‘Hindu in danger’ theme remained close to his heart. When he contested the first Lok Sabha elections in 1952 from the Calcutta South East constituency, the plight of Hindus in East Pakistan was his key campaign plank.

TRYST WITH THE CONGRESS

Mookerjee wrote in his diary that Patel, Nehru and others had persuaded him to join the Congress because of his courageous efforts to retain parts of Bengal, especially Calcutta, with India, but he politely turned it down. He had his share of ideological differences with Gandhi on issues ranging from his economic philosophy, the Congress position on the Muslim League and on the status of Hindi as national language. Mookerjee believed that spinning wheels could resolve the issue of India’s clothing shortage, but it was not enough to make the country a great economic power.

In 1946, when the AICC session was held in Calcutta, Mookerjee was unwell and all senior Congress leaders except Gandhi visited him at his home. Gandhi sent him a note in Hindi before leaving Calcutta. And, Mookerjee replied in Bengali.

Mookerjee was part of independent India’s first cabinet headed by Nehru. “Most people are unaware of the fact that Gandhi and Patel asked Nehru to include Dr Mookerjee in the first cabinet,” said Ganguly of the Syama Prasad Mookerjee Foundation. Mookerjee worked for three years as minister of commerce and industries and prepared the blueprint for several major industrial projects like the Chittaranjan Locomotive Works, the Sindhri Fertiliser Corporation and the Hindustan Aircraft Factory. He quit in 1950 saying India was not doing enough to protect the Hindu minority in Pakistan. A year later, he launched the Bharatiya Jana Sangh, the predecessor of the BJP.

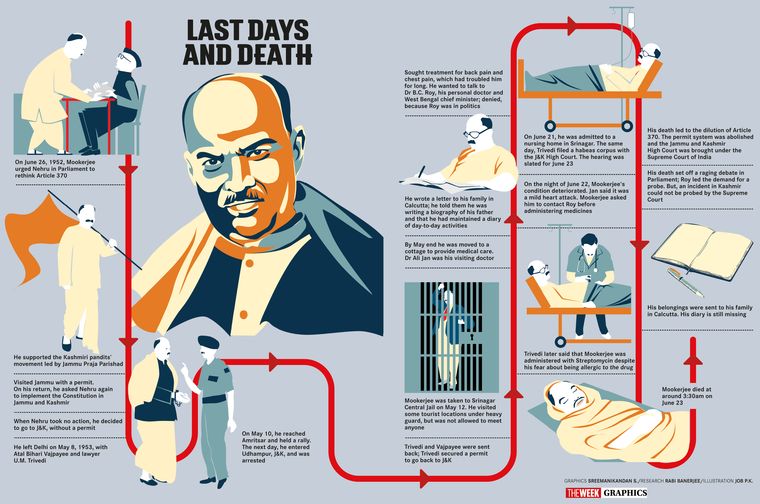

Mookerjee then turned his attention towards achieving Kashmir’s total integration into India. Non-Kashmiris required a permit to visit the state back then. Mookerjee chose to challenge the rule and was arrested on May 11, 1953, upon entering Kashmir. He was held in preventive detention, a provision against which he had vociferously protested in Parliament. As he was suffering from chronic rheumatoid pleurisy and heart ailments, he was soon shifted to a nursing home in Srinagar. But his condition deteriorated and he breathed his last on June 23. Despite multiple requests for an inquiry into his death, there was no probe, and his death remains controversial to this day.

“We differed sometimes very deeply on many issues and we agreed too on many issues and it is a matter of peculiar regret and grief to me that in the last days of his life an occasion arose on which there was very considerable difference between him and me,” Nehru told the Lok Sabha after Mookerjee’s death. “However, we are deprived of the personality who had played such a notable and great part in the country and who was after all fairly young and who had a large and good stretch of years before him. But that was not to be.