So when does the world get back to normal? It is a question that is on the mind of half of the world’s 7.8 billion people who have been asked to stay put at home to avoid a virus that has made millions sick. Not until a good vaccine is developed, Dr Anthony Fauci, America’s top infectious diseases expert, told reporters recently at a White House press briefing.

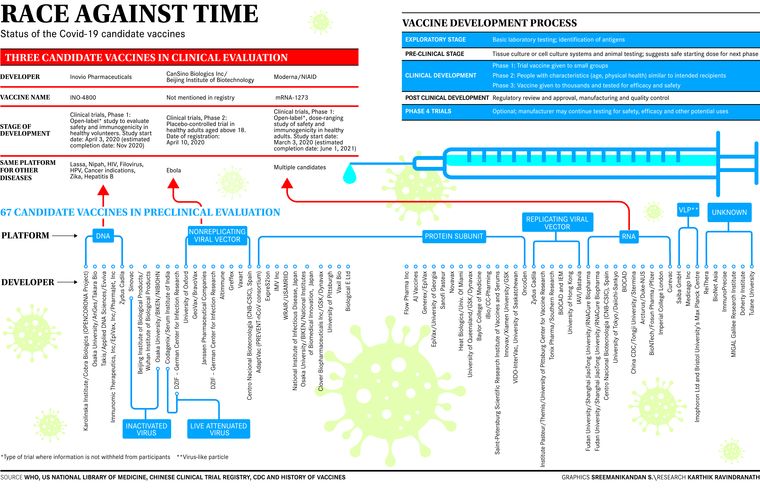

In normal times, experts say developing an effective vaccine would take anywhere between five and 10 years. But these are unprecedented times, and even scientists are being compelled to find newer ways to develop and test vaccines. Best-case scenarios for vaccine development have already shrunk the time frame to 12 to 18 months; globally, more than 100 vaccine candidates are at different stages of development. “Five of these have reached the Phase 1 trials, and 18 are in pre-clinical stage,” said Dr Shahid Jameel, virologist and CEO, Wellcome Trust/DBT India Alliance.

Closer home, Indian scientists, researchers and vaccine manufacturers are racing ahead, after Prime Minister Narendra Modi, in his speech on April 14, asked India’s young scientists and researchers to come forward to work on a vaccine against Covid-19.

For a country that is a leading manufacturer and supplier of vaccines, India definitely has some advantages in building one. According to the department of biotechnology, the government body that is leading the hunt for the vaccine development, four major companies—Serum Institute of India, Zydus Cadila, Bharat Biotech, Biological E Ltd—have a candidate each, besides academic research groups from the Indian Institute of Science, International Centre for Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology, National Institute of Immunology, and Translational Health Science and Technology Institute.

Vaccines are built by taking different approaches, said Jameel. They can either use inactivated viruses (for instance, the injectable polio vaccine); or live attenuated or weakened virus (the oral polio vaccine built in the 1950s) that is weakened to the point that it infects and multiplies, but does not cause disease; or subunit vaccines, where you take a part of the virus (protein), produce en masse and purify it and use it as a vaccine. The idea is to choose the antigens that best stimulate the immune system. One method of production involves isolating the specific protein from the virus or producing it using recombinant DNA technology and then administering it on its own. This reduces the likelihood of adverse reactions to the vaccine. “The hepatitis-B vaccine is one example of that approach,” said Jameel. Besides, vaccines being developed are also either based on DNA, RNA, or vector vaccine-based approaches.

“The selection of an antigen and the antigenic design of the potential candidate will have a profound effect in generating an effective immune response. Since spike protein of the SARS-CoV-2 is a potential target, one will need to decide whether full-length spike glycoprotein or part of the protein that binds with the receptor needs to be selected,” said Professor Sunit K. Singh, head, molecular biology unit, faculty of medicine, Institute of Medical Sciences, Banaras Hindu University.

For now, Premas Biotech seems to have worked around some of those issues. The Gurugram-based company, in collaboration with US-based Akers Biosciences, is working on its vaccine candidate using a mixture of three antigens produced in baker’s yeast. Its cofounder and managing director, Prabuddha Kundu, said that traditionally vaccines were made by injecting heat-killed or attenuated whole viruses or bacteria, but since that had side effects, the approach of late has been to take a part of surface proteins, purify and produce it recombinantly (by rearranging genetic material) to elicit an antibody response.

In the case of SARS-CoV-2, one of the top targets is the spike protein present on the outer surface of the virus, and is understood to be the weapon with which it binds to the human cells (receptors) and gains entry. But since there were concerns about mutations in spike proteins, Kundu said that his team had created a mixture of the spike protein and two other proteins found on the outer membrane of the virus. These, said Kundu, would be replicated on its genetically engineered platform of baker’s yeast (D-CryptTM). The platform has worked in the past, too—it has been successful in expressing 30 proteins similar to those in the structure of the selected Covid-19 antigens. “It is also safer, and cost-effective,” said Kundu, adding that the company has applied for animal trials with the Review Committee on Genetic Manipulation.

In Hyderabad, Bharat Biotech is collaborating with virologists at the University of Wisconsin (UW)-Madison and vaccine company FluGen on a “unique intranasal vaccine” called CoroFlu. The new vaccine is being built on the “backbone” of the trio’s flu vaccine candidate known as M2SR, developed a couple of years ago. “M2SR is a self-limiting version of the influenza virus that induces an immune response against the flu,” said Dr Krishna Ella, chairman and managing director, Bharat Biotech. “[FluGen cofounder Yoshihiro] Kawaoka’s lab will insert gene sequences from SARS-CoV-2 into M2SR so that the new vaccine will also induce immunity against the novel coronavirus.”

Also read

- Volunteer in Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine trials dies. What next?

- COVID-19 vaccine update: Oxford-SII 2nd phase tests begin; minister provides rollout timeline

- India set to play key role in making COVID-19 vaccine, say world's top experts

- India prepares five sites for final phase human trials of Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine

- Serum Institute to begin trials of Oxford's COVID-19 vaccine candidate by August-end

- Serum Institute to seek human trials in India in a week

CoroFlu’s safety and efficacy in animal models is being assessed at the UW-Madison’s influenza research institute, said Ella, which could take four to six months. “Post the results of animal trials, which is crucial, Bharat Biotech will begin production scale-up for safety and efficacy testing in humans. CoroFlu could be in human clinical trials by the fall of 2020,” he said.

Bharat Biotech is also working on a second candidate that will utilise the inactivated rabies vector platform, for which funding has been approved by the department of biotechnology. The department has also recommended funding support to Ahmedabad-based Zydus Cadila for advancing the development of a DNA vaccine candidate, as well as Phase 3 human clinical trials for recombinant BCG vaccine (VPM1002) planned in high-risk population by the Pune-based Serum Institute of India (SII). SII is also testing its vaccine candidate (in collaboration with US-based biotech company Codagenix) on the animal models and hopes to have a vaccine by 2021, its CEO Adar Poonawalla has said.

Despite the urgency, there are challenges in making a vaccine for SARS-CoV-2, said Kundu. “The tools that are normally available to us otherwise are not available here,” he said. For instance, they did not have specific antibodies to test antigens. “Despite that we have been able to work through this by developing surrogate models,” he said.

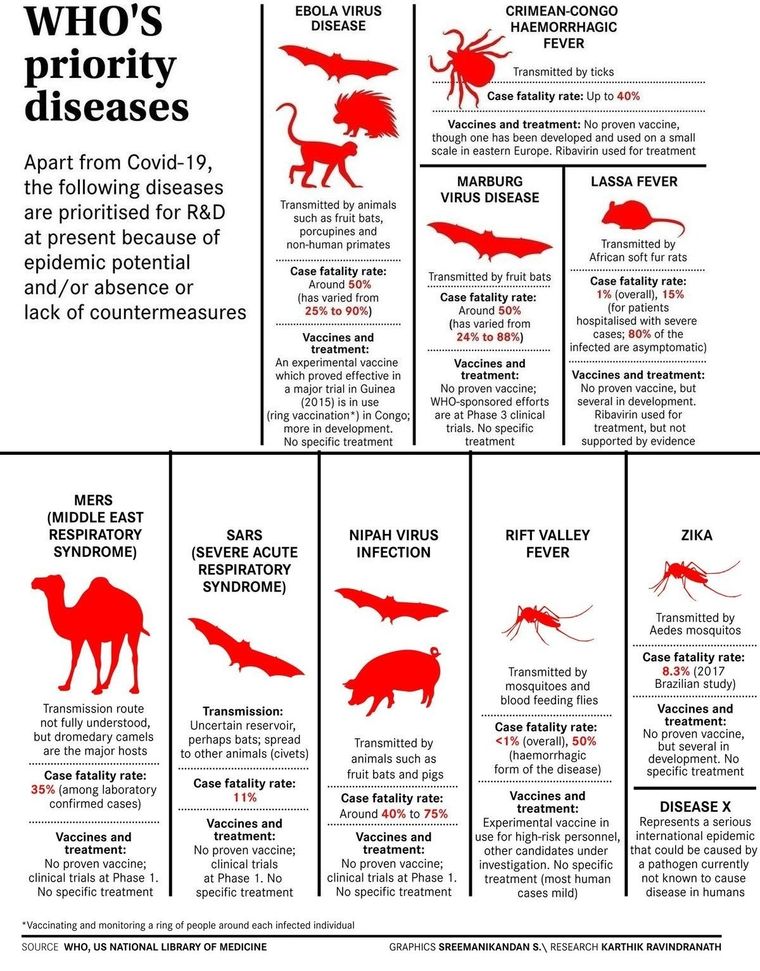

The amount of time that the immunity lasts in the body is also something that is still not known. “In the case of SARS-CoV and MERS infections, the natural immunity does not last long,” said Singh. “Based on that knowledge, one has to also decide the doses of vaccination to be given in order to have immunity for a long time. The challenge to produce in huge quantities to cover the population under a mass vaccination programme will also need to be taken on. That will require a global coalition, and not just a few companies.”

For those working on vaccines, what has helped, said Kundu, is that regulatory pathways are being fast-tracked and regulators are now willing to consider new scientific processes, and collaborations are happening. For instance, two global vaccine manufacturers—Sanofi and GSK—have come together to develop an adjuvant vaccine for Covid-19. Sanofi is providing the antigen that will be produced on its Baculovirus Expression Vector System platform, said its spokesperson. “The recombinant technology produces an exact genetic match to proteins found on the surface of the virus,” the spokesperson told THE WEEK. “GSK will provide its novel adjuvant technology—AS03.”

An adjuvant is a substance that is combined with a vaccine antigen to help stimulate a stronger and more targeted immune response. “This can help provide better protection or in some instances, like a pandemic, could reduce the amount of antigen required per dose, allowing more vaccine doses to be produced and supplied,” said the spokesperson. “This is a critical advantage in a pandemic setting. The AS03 adjuvant will help improve the immune response to the antigen and may also be antigen sparing. Due to the critical need for a vaccine to address Covid-19, Sanofi will be testing its own adjuvant as well.”

According to Jameel, the challenge in building a vaccine against Covid-19 may not be any different from making a vaccine for other diseases. “The power of technology available today is evident from the fact that since the pandemic began in January, we already have more than 100 candidates,” he said. “For India, the opportunity will be in manufacturing the vaccines that are developed eventually and making them affordable for all.”