In late September, as Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan breathed fire and brimstone at the United Nations General Assembly over India’s alleged human rights violations in Jammu and Kashmir, hundreds of protesters outside the New York building were blaming Khan for something similar. These were his own tribesmen—the Pashtuns from Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Lending support to the Pashtuns—who held aloft the banner of the Pashtun Tahafuz Movement—were men and women from Pakistan’s Balochistan and Sindh provinces. Most of them were from the Baloch Republican Party, the Muttahida Qaumi Movement and the Jeay Sindh Muttahida Mahaz.

Their slogans echoed the sentiments of Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan, the Frontier Gandhi, who had decried the 1947 partition with the words: “You have thrown us to the wolves.”

To most Pashtuns, Baloch, people of Gilgit-Baltistan and even the Sindhis, the military-controlled Pakistan state is that wolf; it has been fattening itself at the expense of the tribesmen and the peripheral provinces for years.

At the time of partition, Muhammad Ali Jinnah had justified the creation of Pakistan by pointing to the identity crisis Muslims were facing at the time. However, in the 1970s, problems in the faith-based two-nation theory were exposed. Bangladesh was created based not on religion, but ethnicity and language. And, since then, newer fault lines have appeared on the body politic of Pakistan.

Chief among them is the Baloch movement, spearheaded by the Baloch Republican Party. “The situation in Balochistan is critical,” BRP president Brahumdagh Bugti, living in exile in Geneva for nine years, told THE WEEK. “No day passes without a village being attacked, civilians being harassed or a bullet-riddled body of previously abducted Baloch political activists being dumped in deserted places.”

Bugti himself had a miraculous escape in 2006. The military regime of General Pervez Musharraf had unleashed its firepower in Dera Bugti in Balochistan and had killed Bugti’s grandfather, Nawab Akbar Bugti, a former governor of Balochistan. Bugti, then 24, fled to Afghanistan and stayed there till 2010. He was then granted asylum in Switzerland. The Pakistan government labelled him a terrorist and blamed India for his escape.

While India had mostly been silent about Pakistan’s internal strife, Pakistani rebel groups have been looking to India for moral and material aid.

Then, in his Independence Day speech in 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi said that the Baloch, people of Gilgit-Baltistan and Kashmiris in occupied Kashmir had been thanking him for raising their issues globally. Since then, “The Baloch cause has gained significant traction around the world,” said Bugti.

Balochistan has strategic significance for India as it connects the Indian subcontinent, Central Asia and the Middle East. The people there have ties to both Indian and Central Asian cultures. The Baloch mainly speak two languages—Balochi, which is Indo-Iranian; and Brahui, which has Dravidian roots.

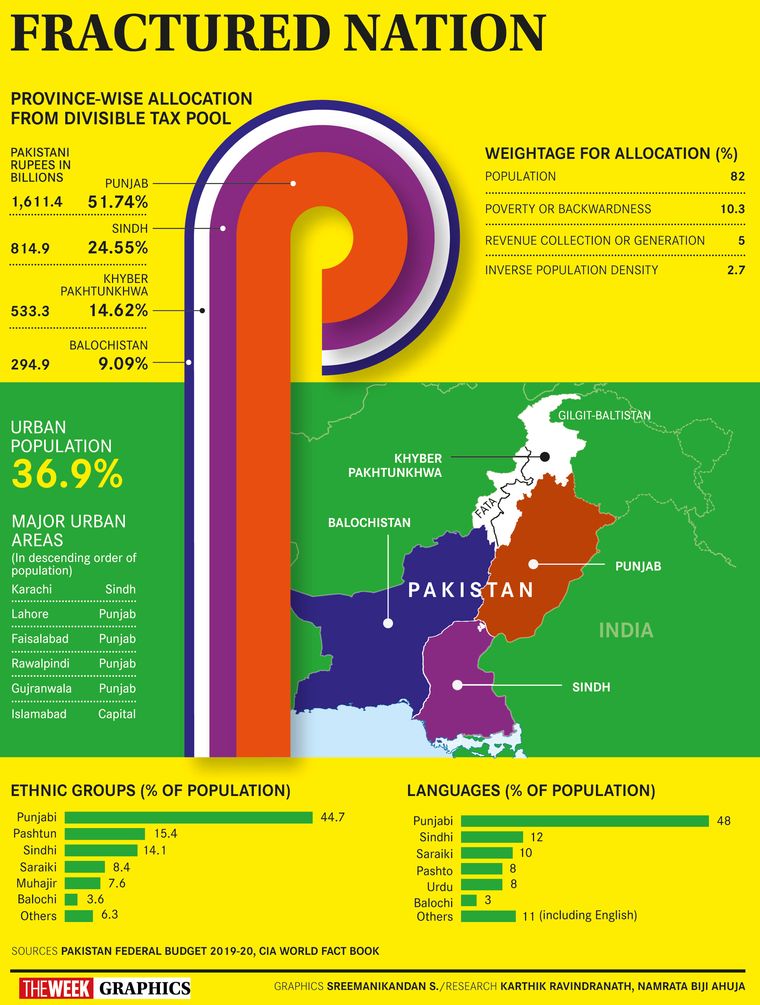

The Baloch allege that Pakistan, dominated by the Punjabi elite, is interested only in the region’s vast mineral reserves and other natural resources, including natural gas reserves said to be worth $1 trillion. The province, whose people are much poorer than the Punjabis and the Sindhis, gets a lower share in the national budget.

Khalil Baloch, chairman of Baloch National Movement (BNM), a prominent mainstream Baloch movement, said if Balochistan became an independent state, it could serve as a bridge between India and Central Asia, bringing peace and stability to the region.

The Baloch independence struggle dates back to 1839, when the Khanate of Kalat, a princely state, was forced to enter into a subsidiary alliance with British India. Khan Mir Mehrab Khan, who refused to surrender, was killed along with his 400 men. Kalat remained in the alliance till August, 1947, when a formal announcement of its independence was made by the standstill agreement, signed between the newly independent dominions of India and Pakistan and the princely states of the British empire. Kalat was independent for seven-and-a-half months; the Pakistan military occupied it on March 27, 1948. Since then, the Baloch resentment against the military has only deepened.

Moreover, the recent plan to build the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor has aggravated the inherent suspicion of the Baloch towards outsiders. “The CPEC is an illegal project; it aims to exploit the land, sea and resources of Balochistan,” said Bugti. “The increasing Chinese influence is dangerous not only for the Baloch, but also for the region and neighbouring countries.”

That the Chinese are building and managing the Gwadar Port has further alienated the Baloch. “The locals are not even allowed to fish, which is the main source of income for many households,” said Bugti.

Even the Human Rights Commission of Pakistan has been critical of the government, and especially the army. In October 2019, a fact-finding team raised concerns about enforced disappearances and targeted killings.

Even minor local issues—hidden CCTV cameras were recently found in women’s washrooms and smoking areas at the University of Balochistan—have added fuel to the fire.

“I wish Modi would realise that he needs to do a lot more,” said Khalil. “I expect the Indian support will not be based on short-term political interests.”

Though India has not given any material or military aid, its moral support to the cause is said to have prompted an uneasy Pakistan to allegedly abduct Indian national Kulbhushan Jadhav and accuse him of spying in Pakistan territory.

“I know for sure that Jadhav was not arrested from Balochistan... but I wish the Pakistani allegations were right,” said Khalil. “I wish India had supported the Baloch cause the way Pakistan is claiming.”

With or without India’s support, the Baloch struggle has of late taken a violent turn, with several armed outfits taking on the Pakistan military, especially its notorious Frontier Corps. So much so that the US recently declared the Baloch Liberation Army a terror outfit, apparently in a bid to mollify Pakistan.

“[The US] must rethink its decision and not follow a policy of appeasement that could be detrimental to the interests of the US and of the international community,” said Hyrbyair Marri, leader of the Free Balochistan Movement.

Many Baloch leaders now dread a fate similar to that of BNM founder Ghulam Mohammed Baloch, whom the Pakistan army allegedly killed in 2009, and BNM general secretary Dr Mannan Baloch, who was also murdered. Marri said that the freedom struggle was getting out of hand with rogue elements taking over. “Two wrongs do not make a right.”

While the Baloch movement continues to simmer, cries of revolution are more recently echoing from the restive Khyber Pakhtunkhwa region of Pakistan. Gulalai Ismail, a Pashtun Tahafuz Movement (PTM) member, made news in September for her sensational escape to the US. The Pakistan military had charged her with sedition, treason and for defaming state institutions. The activist, 32, now lives in Brooklyn, US, with her sister. “As a woman, it is more challenging because I have to fight at multiple levels,” she told THE WEEK. “I am fighting patriarchy, religious extremism and a militarised state all at once.”

Her ordeal began earlier this year when she aired her concerns about the rape of Pakistani women, especially the Pashtuns in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, on social media. She later became active in PTM protests and was one day told, by a friend, that a raid team was going to pick her up. She fled with bare essentials. “It is one of those moments when you do not have the time to feel frightened,” she said. Interestingly, Gulalai had won the prestigious Anna Politkovskaya award for human rights advocacy in 2017.

She continues her fight from Brooklyn, but is concerned about the safety of her parents in Pakistan. She said that instead of fighting the Taliban, the Pakistan security agencies were going after human rights activists. “The authorities are harassing my father as they could not lay their hands on me,” she said.

The Federal Investigation Agency arrested Muhammad Ismail for “hate speech and [spreading] false information against government institutions in Pakistan”. US assistant secretary of state Alice G. Wells, in-charge of South Asia affairs at the state department, has expressed concern over “reports of the continued harassment” of Gulalai’s family and her father’s detention.

The Pashtun’s freedom movement started in the 1950s. There was a call for an independent Pashtunistan, a historical region inhabited by the indigenous Pashtuns, now divided between Pakistan and Afghanistan. This demand continues to strain relations between the two countries.

The Pashtuns allege that they have been used as war fodder by the Pakistani establishment in its “dubious” fight against terror. When the army launched operation Zarb-e-Azb in 2014 (to fight terror near the Durand Line), the Pashtuns were sandwiched between the forces and terror outfits. They accused the Punjabi-dominated army of sheltering the terrorists they claimed to be fighting. These terror groups then tried to oust the Pashtuns from their own land, and when the Pashtuns resisted, the army, they claim, cracked down on them.

In May this year, the Pakistan army arrested two PTM parliamentarians—Ali Wazir and Mohsin Dawar—while allegedly firing on protesters near the Kharqamar checkpost in North Waziristan. The military’s public relations department later claimed that the armed protestors had initiated the gunfight. Wazir and Dawar were released in September.

Imtiaz Wazir, former chairman of the Pakhtun Students Federation—a student wing of the Pashtun nationalist Awami National Party—wants to unite students’ groups of the Pashtuns, the Baloch, the Sindhis, the Mohajirs and the Kashmiris. Imtiaz was born and brought up in North Waziristan, and has worked in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and the Federally Administered Tribal Area (a semi-autonomous region in northwestern Pakistan). A few years ago, he was forced into exile in Afghanistan and lived there for more than three years. He relocated to the UAE three months ago and has now applied for asylum in India.

Speaking exclusively to THE WEEK, Imtiaz said Pakistan had raised the Kashmir issue at the UNGA to divert public attention from genuine concerns. “The small ethnic and religious minorities in Pakistan have rejected the Pakistani narrative on Kashmir and stand by the Indian government and the peace-loving people of Kashmir,” he said. “My people and the Hindus lived together in Waziristan and other Pashtun areas as good neighbours for a long time. We are working on strengthening our mutual relationship.”

Imtiaz claimed that, in the past 16 years, the Pakistan military had killed at least 70,000 Pashtuns and had made many more “disappear”. “We fear Pakistan will send a larger number of its terrorists to Kashmir,” he said. “The Indian government and the international community must remain vigilant and Pakistan must be held accountable for any unpleasant situations.”

He also accused the Pakistani military of having a nexus with more than 75 terror groups on its soil. “We urge the US and EU members to impose economic and diplomatic sanctions on Pakistan and place the country’s military on a blacklist to force it to abandon its terror project,” he said.

He said the Taliban has been recruiting and training militants to restore its dominance across the Pashtun belt in Pakistan. “The Afghan Taliban and the Haqqani Network are freely operating and opening new offices in various districts of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan,” he said.

The Pashtuns are clearly worried, but so are the Urdu-speaking Mohajirs. They are Muslims who migrated to Pakistan from various parts of India after partition, and a large chunk of them settled in Sindh. But, over the years, they claimed to have faced discrimination and have become vocal about the demand for an autonomous region of Greater Karachi.

The Karachi-based Muttahida Qaumi Movement (MQM), previously the Mohajir Qaumi Movement, is one of the biggest political parties fighting for the Mohajirs. Its founder Altaf Hussain, living in exile in the UK since 1992, recently released a video appealing for asylum in India. In it, he said, “If India and Prime Minister Modi allow, I am ready to come to India with my colleagues because my grandfather, my grandmother and thousands of my relatives are buried there. I want to go to their graves and pray. I shall remain apolitical and continue my struggle from India. I request India to give asylum to a few Sindhis and the Baloch as well, who could continue fighting in a peaceful manner [from there].”

He added that India should support him at the International Court of Justice, where he will fight for the right of all the ethnic religious minorities of Pakistan.

Speaking to THE WEEK from his home in Mill Hill, London, he said, “I would urge the people of India not to forget that the Mohajirs were part of India before the partition. Our forefathers were misguided and trapped in the name of religion and participated in the movement for the division of the Indian sub-continent. It was a blunder and we are paying the price in Pakistan.”

Hussain, however, has not made a formal request for asylum. “I just expressed my views. I appealed to the Indian government for my people who are facing a brutal state operation since 1992.”

Hussain’s plea request, which has gone viral, has reached the ears of not just New Delhi, but also Islamabad. The biggest worry for Pakistan is that Hussain’s statement could trigger similar requests from other dissident groups.

The MQM recently built a “unity and alliance of oppressed nations” with the Mohajirs, the Baloch, the Sindhis and the Pashtuns. All four groups are planning to raise the issue of Pakistan-sponsored terrorism on the 11th anniversary of the Mumbai 26/11 attacks, by holding protests in various parts of the world.

With Imran Khan publicly supporting banned Khalistani leaders after opening the Kartarpur corridor, besides speaking on the Kashmir issue, India has got multiple counters, Hussain’s plea being the latest. Will India play this card or any other must have already been deliberated upon, although it may never be made public.

Also read

- 'Kulbhushan Jadhav was not arrested from Balochistan'

- 'Pakistani military using US aid for genocide of Pashtuns'

- 'Independence of Balochistan will benefit India in the long run'

- Pakistan has been playing dubious role in war against terrorism

- Sindh is a victim of political tyranny and exploitation

- Pakistan army accuses us of working for India: Activist Gulalai Ismail

- Fighter jets cannot be compared with pellet guns

Hussain’s plea comes at a time when Imran Khan is facing domestic trouble and the MQM is trying to revive its political significance. Dr Ashok K. Behuria, senior fellow and coordinator of the South Asia Centre at Institute for Defence Studies and Analyses, Delhi, said that Hussain could be trying to gain political mileage by reaching out to India now. “New Delhi does not have a uniform policy on the asylum issue, and Hussain’s appeal, in case it is made in a formal manner, should be treated strictly on the merit of the case, rather than on political considerations to spite any country, especially at a time when Pakistan is bent on sullying India’s image at the international level,” he said.

The Mohajirs apart, the Sindhis in Pakistan, too, have claimed to be victims of human rights abuse and religious fundamentalism. At the forefront of their struggle is the Jeay Sindh Muttahida Mahaz, which was declared a terror group by Pakistan in 2013.

Sindh is where maximum polarisation took place after partition. It was felt that Punjabi dominance, coupled with the inundation of the Urdu-speaking Mohajirs, was eroding the Sindhi identity. The idea of a separate Sindhudesh was born after Sindhi leader G.M. Syed drew inspiration from the Bengali language movement, which culminated in the Bangladesh Liberation War.

Syed became the first nationalist politician to demand independence from Pakistan. Today, JSMM chairman Shafi Burfat is steering the Sindhi struggle after being forced to flee Pakistan and take exile in Germany. “The partition of India rendered the rule of historically independent [people] like the Sindhis, the Bengalis, the Pashtuns, the Baloch and the Kashmiris into the hands of the Punjabi civil bureaucracy and the mercenary Punjabi army (both loyal to the British Raj) in the name of Pakistan,” he said.

The real identity crisis began when these nations were forced to abandon their pluralist cultures and politico-economic authority, he said. The Sindhis started their struggle for national rights in 1948, but wanted total independence in 1972. They claim to have suffered since.

“The Bengalis, being a satellite province and the better half of Pakistan, seceded through a struggle, after a mass genocide by the fascist Punjabi army in 1971, with the timely interference by India,” he said. “But the other nations, which were much weaker and smaller than Punjab, are struggling for their existential survival in Pakistan.”

Burfat cautioned Delhi against taking decisions to spite Islamabad, like choking Pakistan’s water supply from the Indus. India has often thought about this. “Punjab in Pakistan has already built illegal canals, reservoirs and dams on the Indus and has robbed Sindh of its water by force,” he said. “Any step by India to stop the Indus would heavily damage its friendly image in Sindh.”

These warnings aside, the rebel groups have largely been warming up to India. Pakistan, however, is in denial mode. Speaking to THE WEEK from Islamabad, Bashir Wali, former director of the Pakistani Intelligence Bureau, said that these movements have no traction. “If you ask anyone in Pakistan, they would not even acknowledge these movements exist,” he said. “It is a non-issue. There is no such thing as resistance movements in Pakistan.”

Behuria said Delhi’s policy of non-interference in internal affairs of other states has prevented it from exposing Pakistan’s fault-lines at international forums.

“Whether it is by acts of omission or commission, Pakistan is complicit of violating its own constitution, which recognises the rights of minorities,” he said.

Behuria hailed the BJP government’s policy to grant refugee status to persecuted Hindu migrants from Pakistan. Official data shows that 36,000 Pakistani Hindus were granted long-term visas between 2011 and 2018. These families, living in Delhi, Punjab, Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, have started applying for Indian citizenship. Similarly, India’s focused interest in its northern frontier was a much-awaited move, said defence strategists. “Gilgit and so-called Azad Kashmir were legitimate parts of the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir at the time of its accession to India,” he said. “So, when the Indian physical map is redrawn after removal of the special status, Indian claims on these parts occupied by Pakistan remain legitimate.”

As the fault-lines in Pakistan grow deeper, the highhandedness of its government may only fuel the fire. The tribals feel Imran Khan has reneged on his election promises. Khan had, on many occasions, accused the military and the ISI of killing innocent Baloch and suppressing the Pashtuns. Today, Khan seems to be justifying the actions of the same military and the ISI.

Only time can tell the future of these movements. But, one thing is certain—if the demographic lines of the subcontinent are to be redrawn, the process will be bloodier than before.