India does have a national cuisine. I confidently assert this after 20 years of exploring and writing about Indian food. This work has taken me to almost every corner of the country, into all kinds of kitchens from rural to royal. I have had conversations with hundreds of domestic and professional cooks, and enjoyed countless meals.

I am aware of a particular decisive, nationalistic ideal about food that has emerged over recent years. It is not my intention to feed this (pun unintended), rather to defuse it. India’s national cuisine is her regional cuisines, every one of them—from the kalari kulcha of Jammu and the chhena poda of Orissa to the raw fish and wild greens soup called pasa of Arunachal Pradesh and the ker sangri of Rajasthan. They have been developed over thousands of years. Every caste and creed has made a unique contribution to creating a food culture so varied and finely nuanced that it makes up the world’s most diverse cuisine. In my opinion, it is also the most remarkable and complex food culture in the world. Its unparalleled combinations of flavours and textures make it the most exciting to eat.

Also read

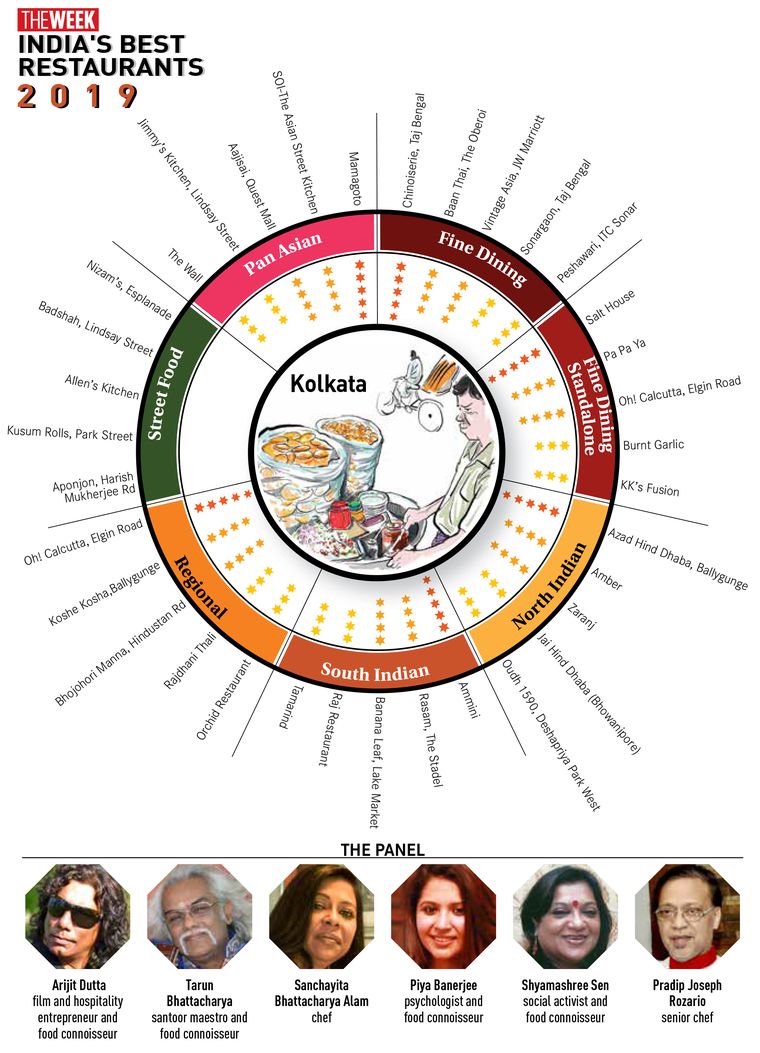

- The best restaurants in Kolkata in 2019

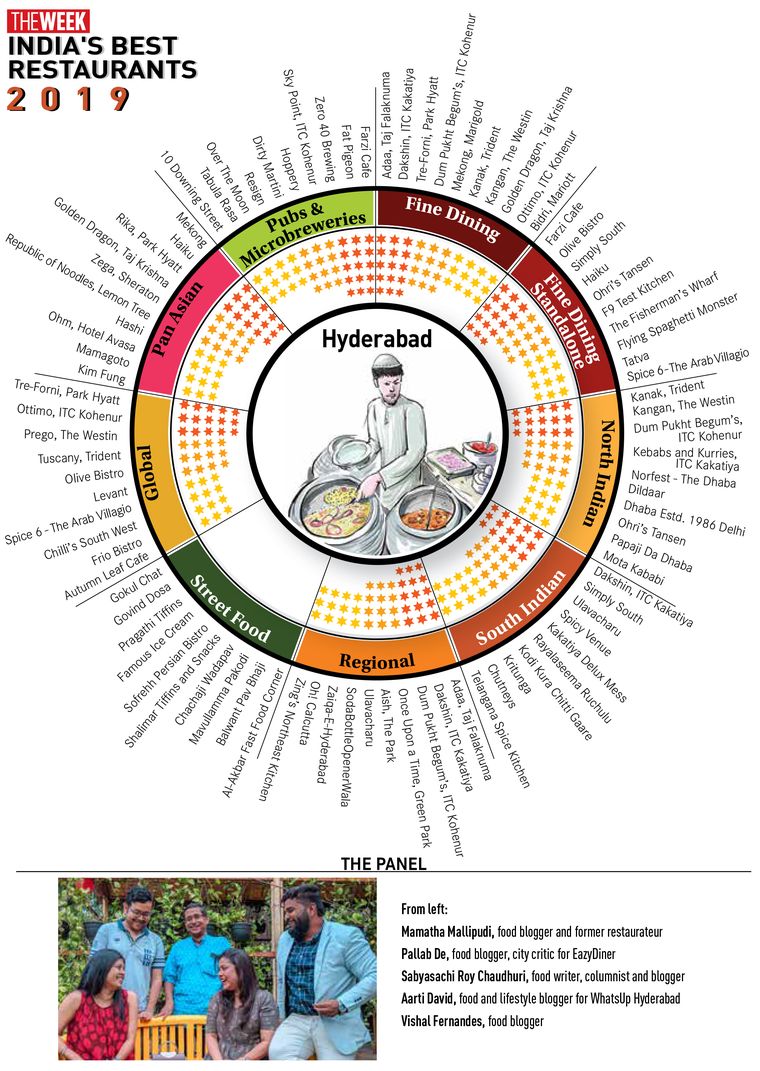

- The best restaurants in Hyderabad in 2019

- The best restaurants in Mumbai in 2019

- The best restaurants in Bengaluru in 2019

- The best restaurants in Chennai in 2019

- The best restaurants in Kochi in 2019

- The best restaurants in Delhi in 2019

- Back to the land

- Far east, near home

- Muse of mixology

The first time I came to India I did not come for the food. My only experience of it had been in Indian restaurants outside India, serving dishes from predominantly the northern part of the country, with a ‘chicken vindaloo’ and a ‘Madras prawn curry’ thrown in for good measure. Each of the dishes, all called curry, was almost indistinguishable from the other, made with too much oil and chili. The homogeneity of these offerings suggested to me that this was Indian food—a ‘national cuisine’. What a revelation it was to discover otherwise.

As I travelled around India on this seminal visit, I noticed that, after every few hundred kilometres or so, the snacks and small meals served at railway stations and street food stalls changed. I had trained as a professional cook, and was a budding food historian then, so I was attuned to observing what people around me were eating, and my culinary curiosity was aroused. One evening, I was looking for somewhere to have dinner in Hospet, Karnataka, and I spotted a bustling restaurant. The signage was in Kannada, which gave me no idea of what was on offer, but I trusted my instinct that a place full of locals was likely to have good food. I sat down at a spare table. A plate of rice was placed before me, accompanied by a few small dishes and various sauce-like concoctions. There was no cutlery. I looked around to see how others were managing. I saw that they poured the sauces over the rice and mashed it into small balls, which they picked up and delicately ‘flicked’ into their mouths. I imitated them, and what followed can only be described as life-changing. I had never tasted anything like this food; it was zinging with flavour. It steered my palate and my intellect towards what has become my life’s course. In that restaurant, at that moment, I decided I was going to write a book about India’s real cuisine—her regional food. What resulted was The Penguin Food Guide to India. Yet, my appetite for exploring Indian food is barely satiated. I am currently focused on the country’s contemporary food-scape.

In a recent article which appeared in an Australian newspaper, about the success of Masterchef Australia in India, the journalist described the subcontinent as the “land of cricket and curries”. The notion that India has a uniform national cuisine comprising something singularly called ‘curry’ remains strongly entrenched in western countries. This is largely because a limited representation of Indian cuisine still prevails in many ‘Bengal Tiger’ and ‘Star of India’ restaurants, including in tourist joints in India.

I also discovered that while many Indians knew their country had different regional cuisines, they were often unaware of what these might be like, beyond a few, usually unappetising, stereotypes. For example, the general belief was that food in the south had “too much coconut oil” and was “too spicy”. I recall visiting a holiday resort in Kerala that served exquisite regional food. But many of the guests from north India turned up their noses at these local preparations of fresh seafood and tropical vegetables, and ordered the more familiar dishes on offer. This was not that long ago, but I am certain if I went back to that same establishment, I would find these same patrons enthusiastically tucking into its local food, as an eager appreciation for regional cuisine has emerged across India, most evidently in restaurants.

Why then, has India’s regional cuisine not gotten the recognition it deserves, and why is it now being taken up so enthusiastically? The answers are multifaceted, but permit me to address just two of the key factors. Regional cuisine has predominantly been confined to home kitchens. There was also the prevalent mindset that what was served in restaurants had to be something “worth” paying for, something that was different to “home food”. Hence, Indian restaurant menus tended to feature erstwhile royal or elaborate special-occasion dishes. I found I often had to convince people, who generously took me into their kitchens, that I really did want to learn about their ‘everyday’ food, as they could not conceive of this being worthy of wider interest.

A significant change today is that the Indian home is changing. People are moving away from joint families, where someone usually cooks, to live in smaller set-ups in big cities. Also, with growing participation of women in the workforce, ever-increasing daily commutes, and obsession with screen-based entertainment, people have far less time and inclination to prepare meals. Many do not even know how to cook. What they do have are increasing incomes, access to meal aggregation services and instant meal options. Inevitably, people start to miss home food. Savvy restaurateurs have responded by offering these familiar dishes in their restaurants, and in doing so, have made different regional cuisines more accessible to a wider audience.

An interest in trying out new cuisines has long been attributed to increasing affluence and social mobility. However, there is a distinctly contemporary factor that has been critical in bringing regional cuisines from homes to restaurants. I call this the ‘Masterchef effect’—the atomic boom in food-focused media in India, encompassing television, smart phones and cookbooks. This has created a heightened interest in cookery shows, eating out and food-focused travel. Here are some of my favourite restaurants in India to sample regional food:

Visit the coastal region of north Kerala to explore the distinctive food of the Moplah community. Their cuisine blends classic Indo-Muslim dishes with the coastal and tropical foods of their locale—fish, coconut, tamarind, curry leaves and rice. And a rich garam masala ground from aniseed, mace, star anise, cardamom, pepper, cinnamon and nutmeg. Try Moplah dishes at Zains Hotel and Paragon in Kozhikode. Take a walk down Sweetmeat Street to sample the local halwa. From October to December, try the crisp, fried, seasonal mussels sold in seaside stalls. To taste the best of Moplah cuisine, stay at Ayisha Manzil, a delightful boutique guesthouse in Thalassery.

Each of the seven states in the North East has its own distinct cuisine. The region is a must-visit for the adventurous food explorer. It is one of the most bio-diverse in India. One of the distinctive features of its food is the use of a large variety of wild, leafy green vegetables and herbs collected from forests, alpine meadows and river banks. There is a huge trend for fermented foods in the west, so it might be of interest to discover some of the 250 types of fermented foods and drinks produced in the northeast. As there are not many restaurant options, visit local markets and sample food from small vendors and street stalls. In Guwahati and Assam, Khorika and Paradise are good for local cuisine. In the Margherita district of Assam, visit Singpho Village restaurant to try the home-style food of the Singpho tribe.

In Bengaluru, one of my most recent discoveries was the Bengaluru Oota Company, a type of ‘restaurant’ that I think exemplifies several key facets of contemporary Indian food. It was started by two women, Vishal Shetty and Divya Prabhakar, who had a passion for food and hospitality, but did not want to open a traditional restaurant. Instead, they chose to convert a classic, small, mud-walled house into a 35-seat eatery and serve the regional food of their respective Mangalorean and Gowda communities. The cooking is done by local women. You have to book at least a day in advance. The menu changes frequently to encompass what is local, seasonal and available in the market on that day. While dietary preferences are accommodated, you do not choose what you eat. Just as if you were having a meal at a friend’s, this is regional cuisine out of the private home and into a place that feels like home.

Charmaine O’Brien is a culinary historian and author of several books on Indian cuisine, including The Penguin Food Guide to India, the first comprehensive work on Indian regional food.