I wasn’t expecting to react as strongly as I did when I visited Jallianwala Bagh.... I certainly wasn’t expecting to cry.

I’d imagined I’d struggle to connect with the horror, that it would seem abstract; an episode from a distant history... the garden is resonant with its memory. When you see the bullet holes that pock the walls, or peer into the well where so many died, you can’t help but imagine the terror the protestors must have felt.

My tears hijacked me when the time came to say goodbye to Mukherji. As chairman of the Jallianwala Bagh board, Sukumar Mukherji—‘SK’—is in charge of the garden. He had very kindly given me a personal tour and, as I thanked him for his hospitality, my voice faltered and I began to weep.

He didn’t seem surprised. Apparently, it is common for Indians and Britishers alike, to be overcome by emotion when they visit the site. But I have more reason than most to feel ashamed and humbled by what happened at the Bagh.

That’s because the demonstrators who were killed by British troops had gathered there to protest against a repressive law inspired by and named after my great-grandfather. I am talking about the infamous Rowlatt Act. The passage of what Gandhi called the ‘Black Act’ led directly to the events at Amritsar on 13 April 1919.

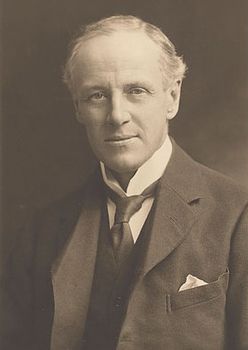

It was a truly draconian piece of legislation. The law suspended the most basic of civil liberties for those suspected of plotting against the Empire. It provided for stricter control of the press, allowed the authorities to arrest anyone who seemed suspicious to them without warrants, permitted indefinite detention without trial. You could be imprisoned for up to two years simply for running a ‘seditious’ newspaper. That is why thousands of Indians gathered in Jallianwala Bagh that day: Urged by Gandhi, they were there to express their disgust and fury at the legislation my great-grandfather, Sidney Rowlatt, had authored.

My link to this dreadful episode had been very much on my mind when I came to live in India with my wife and four children in February 2015. I was worried that my family name would make us targets for any lingering anger. It might also make it hard for me to do my job: Wouldn’t being a scion of an emblem of imperial evil be a handicap in my new role as the BBC’s South Asia correspondent?

A century on, it is worth remembering just how appalling what happened at Amritsar was.

Mukherji had led me along the route the commander of British forces, Brigadier General Reginald Dyer, took with his troops.... He showed me the well into which terrified people had dived for cover. One hundred and twenty bodies were recovered from it. As we turned back to the garden, Mukherji recalled his grandfather telling him how, their ammunition now almost exhausted, the General had ordered his troops to pack up and leave. The wounded were left writhing in agony on the ground. Dyer ordered a curfew, threatening to shoot any Indian seen out on the streets.

The Amritsar massacre was a turning point in Indian history.... Mahatma Gandhi, then a relatively marginal figure among India’s nationalist leaders, launched his first ‘satyagraha’—campaign of non-violence—in protest at the Rowlatt Act. According to the course book used by tens of millions of Indian high school students, ‘it was the Rowlatt Satyagraha that made Gandhiji into a truly national leader.’

After I’d wiped away my tears and recovered my composure, Mukherji and I weaved our way back through the crowds of Indian schoolchildren. I told him I was astonished that he appeared to feel no animosity towards me. ‘You feel shame, so I feel no anger towards you,’ he said....

Mukherji is right about shame, I reflected. I feel deeply ashamed of my connection to this appalling episode.... But do I—should I—feel in any way responsible?

Extracted with permission from the book, Khooni Vaisakhi published by HarperCollins India.