On the surface of it, there is little in common between Petyr Baelish and Donald Trump. Yet Baelish, or ‘Littlefinger’, seems to have encapsulated the US president’s philosophy on all that he has wreaked on the world in the past few days.

“Chaos isn’t a pit. Chaos is a ladder.”

That’s what Littlefinger told Lord Varys in season 3 of Game of Thrones, explaining how there could be a method in madness, how chaotic situations can be confusing yet ripe for the picking by the dextrous player who is aware of the high stakes and the high risks. “Many who try to climb it fail and never get to try again. The fall breaks them. And some are given a chance to climb. They refuse, they cling to the realm or the gods or love. Illusions. Only the ladder is real. The climb is all there is,” goes the famed monologue.

Does The Don know the high risks involved? And how exactly is he going to climb up the ladder from all these chaos?

Trump’s ‘Liberation Day’ tariffs came as a shock even to a world that was bracing for it, with sweeping import duties on almost all of America’s trading partners, with some special ‘love’ thrown at certain sectors like automobiles. The reason was that most nations had imposed higher import duties on American products, compared to the duties their own exports faced while coming to America. The US is the top importer in the world, with goods worth about $3.2 trillion landing up at its ports last year―that is almost as much as the total GDP of India.

“I don’t want anything to go down, but sometimes you have to take medicine to fix something,” Trump told the media.

But, as markets tanked, China retaliated and nations of the world strapped on their seatbelts and got into brace position. The question is, will the world now need an antidote to this medicine?

“The US still drives the world’s growth to a large extent, and many economies directly or indirectly are reliant on the US. If the new tariffs are not rolled back to some extent at least, there is a high chance the US economy itself will suffer significantly. If that is the case, the impact will not be limited to certain export sectors or certain countries. It will have larger impact globally, including on India,” said Vidya Mahambare, Union Bank Chair professor of economics and director (research) at Great Lakes Institute of Management, Chennai. “So it really depends on what happens in the weeks ahead and how long Trump can hold on to what he has announced.”

The alternative could be dire. Singapore Prime Minister Lawrence Wong, who went live in an address to a panicked nation that depends on global trade for survival, put it succinctly, “Liberation Day announcements by the US marks a seismic change in global order. The era of rules-based globalisation and free trade is over.”

It is no secret that Trump’s crosshairs are pointed at its neighbours (and big trading partners) Mexico and Canada, who use their proximity to access the US market, and the old ally Europe, which has shrewdly been using America as a geopolitical bodyguard as well as a lucrative market.

And then there’s China. Since trade relations were normalised between the two countries back in 2000, traffic has mostly been one way. In 2000, Chinese exports to America was $83 billion more than American exports to China; last year this deficit had ballooned to nearly $300 billion.

Beijing has used opportunity after opportunity to advance its position―from a Most Favoured Nation status by the US back in 1979 to normalising open trade and pushing for globalisation post the Cold War via the GATT and WTO negotiations which turned it to the ‘factory to the world’.

China, of course, was not going to take the crippling tariffs lying down, and has imposed reciprocal tariffs. “Because it’s a retaliation from the US across the globe, the retaliation to the US will also be across the globe,” said Madhavi Arora, chief economist with Emkay Global.

India is right now lost in the chaos, despite knowing that there could be an opportunity in all this. Prime Minister Narendra Modi was one of the first world leaders to meet Trump after he took office in January, and he sealed a deal to double bilateral trade to $500 billion by the end of this decade. More importantly, the countries might sign a bilateral trade agreement (BTA) by this autumn.

For the moment, India has decided to play it cool, with no plans to impose any reciprocal tariffs on the US, even while making overtures to Washington for a possible scaling down of the percentages. But is enough strategising happening on the opportunities the current chaos offer? How will India make use of the fact that many countries it was competing with have been slapped with higher tariffs, thus ostensibly giving it an advantage?

“If we have an advantage in the near term with a less tariff than other exporting countries, to become more competitive the government should provide production-linked incentives and capital incentives to expand the manufacturing supply base,” said Ankit Jaipuria, co-founder of ZYOD, an export-oriented textile sector manufacturing firm.

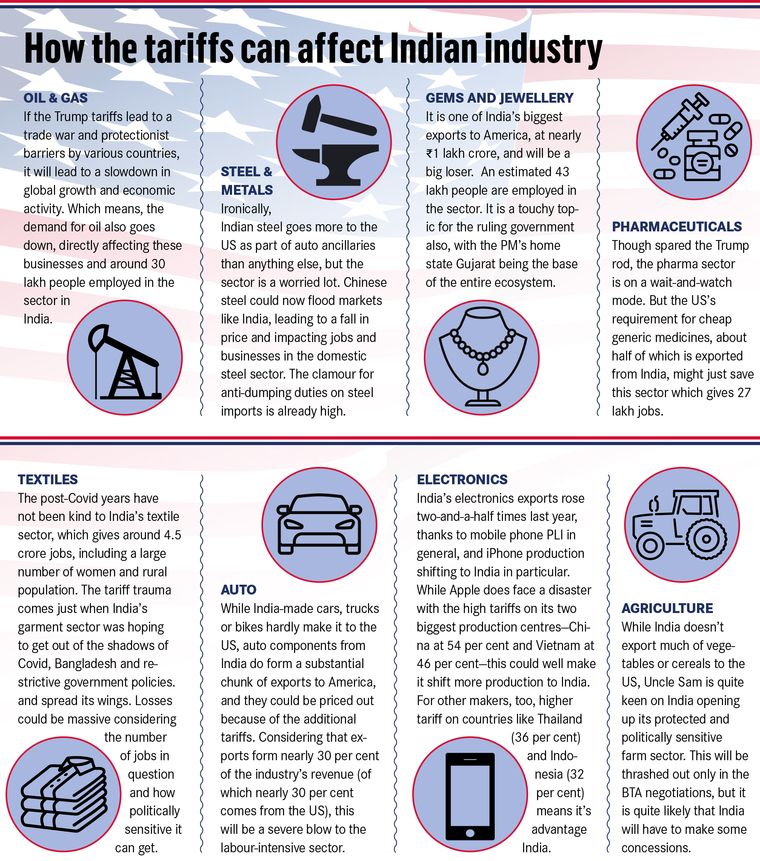

While India’s pharmaceutical sector, which supplies about half of the US’s generic drugs, has been spared, the auto components sector has hit a rough road. “Indian auto component industry generates 30 per cent of its revenues from exports, of which nearly 30 per cent is from the US. This may take some hit either due to lower sales or lower margins,” said Mrunmayee Joglekar, analyst at Asit C. Mehta Investment Intermediates.

Whether the government is focused only on rationalising tariff and sewing up a BTA or it is equally proactive on future strategies on expanding India’s export portfolio need to be seen. This is because it is not just about what you gain or what you lose―many scenarios are to be looked into and strategies developed at a policy level.

One lesser worry is the shutting down of raw materials, especially in the sensitive rare earths, renewable energy and nuclear technology space once a trade war starts raging. The second, and bigger, worry is the fear of big producers like China dumping products cheap in big markets like India.

The steel sector is particularly rattled about the latter. “Duty on Chinese steel in the US was 25 per cent; now it has been increased to 54 per cent. So they are going to dump everything in India and other countries,” said Panckaj N. Umrania, executive director at KND, a steel maker.

Immediate gains or losses apart, India would need to tighten its loincloth and take a hard look at what it wants.

“There will be a whole lot of simultaneous negotiations. With everybody, not just the US,” said Arora. “We have to be nimble, we have to be more strategic. And not just with the US and our existing trade partners, but with new ones. Everybody will be looking for new trade partners.”

India will have to look at improving capacities. The truth is that it doesn’t have the technology, manpower or production capacity to step in to fill the gap left by China and Vietnam in electronics, or Bangladesh in textiles.

Efficiency is another lacuna. While India’s industrial capacity utilisation averages above 70 per cent for big industries, it can be as low as 33 per cent for small scale units.

“What India needs to work upon is a focused process-oriented approach where it can provide cost benefit, cost efficiencies and reliability to global players,” said Jaipuria. “If through policy and collective action we are able to solve this, India is at the right place at the right time.”