The air was smokey and sulphurous,” said Varun Sivaram about what greeted him when he got off a train in Korba, deep in Chhattisgarh. With more than a dozen coal-fired power plants as well as India’s largest open-pit coal mine, Korba is a crucial link in India’s power sector, producing cheap electricity that powers the country’s development aspirations.

Korba is also one of the most polluted places on earth.

For Sivaram, senior adviser to US Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry, Korba is a “hellscape,” symbolic of India’s “deadly addiction” to cheap power from coal. To him, the question is simple, “Should India sacrifice development for breathable air?”

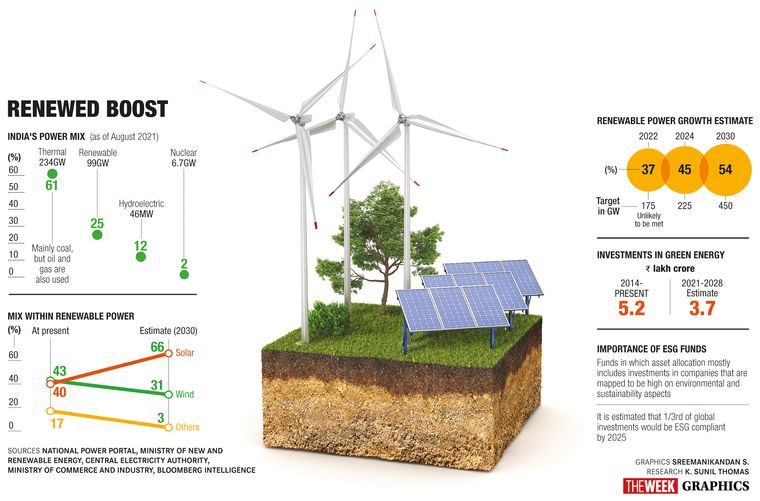

Two-thirds of India’s energy needs are met by polluting fossil fuels—primarily coal, but also oil and gas. India is the only major country that is increasing its coal consumption. Not surprising, as it has coal reserves that can satisfy its energy needs for at least 300 years. That lure of cheap energy, however, comes with a lethal sting in its tail—carbon emissions that are the third highest in the world, leading to not just air pollution, but global warming and climate change.

“There is huge international pressure on India to reduce,” said Debasish Mishra, partner at Deloitte India. “The only way that can happen is renewable energy, through solar plus storage.”

India has been lumbering along on increasing its non-polluting renewable energy capacity by setting up solar and wind farms over the years. But, lack of economic viability and little interest from state governments and distribution companies were obvious. India has often missed its clean energy targets, and will most likely miss the ambitious one to achieve 175 gigawatts (GW) of power through renewable sources by 2022. Currently, the total capacity, including small hydel projects, is estimated to be around just 100GW.

Cue in the richest man in the country to shake things up.

“We will transform our legacy business into a sustainable, circular and net-zero carbon materials business…(and) help transition India and the world from an industrial civilisation to an ecological civilisation,” declared Mukesh Ambani at the annual general meeting of Reliance Industries in July, signalling a pivotal shift for the conglomerate.

Reliance plans to pump in Rs75,000 crore into its new energy business, the biggest single investment in green energy in India. The plan includes building four factories to manufacture critical components for an end-to-end renewable energy ecosystem—solar photovoltaic (PV) modules, storage batteries, electrolysers to split hydrogen from water, and fuel cells to convert hydrogen into mobile and stationary power.

“Surya dev has blessed India with almost limitless sunlight,” Ambani said. “I envision a future when our country will be transformed from a large importer of fossil fuels to a large exporter of clean, solar energy solutions.”

For Reliance, it is both a paradigm shift that was the need of the hour and an opportunity it could not let go by. The company’s foundation is in oil and petrochemicals, which is likely to slow down in the years to come, and just like its foray into telecom and retail last decade, another shift was in order. The Union government’s production-linked incentive scheme (PLI) for solar PVs notified in April, which offers Rs4,500 crore in benefits to those who set up manufacturing units, has only sweetened the deal.

“The potential for renewable energy in India is nearly 1,000GW (currently we are at around 100GW). The economic impact of achieving the Paris agreement targets could boost the global economy by $26 trillion by 2030 and create 24 million jobs. This highlights the potential for this sector and justifies the interest shown by corporate powerhouses,” said Divakar Vijayasarathy, founder and managing partner of DVS Advisors LLP.

Ambani’s foray into green energy is significant beyond the investment amount or the fact that he will square off with fellow Gujarati billionaire Gautam Adani in a battle royale for the ‘green pie’. Adani is planning to invest $20 billion in 10 years across renewable energy generation, component manufacturing, transmission and distribution.

The sudden gold rush of big guns from private and public sectors into green energy could literally transform the face of India. “There is a huge interest from corporates who have installed some large capacities,” said Sanjay Aggarwal, president of the PHD Chamber of Commerce and Industry. “A lot of players have grown fast, because of the FDI and valuation they have been able to attract.”

Tata Power has announced that it would no longer build coal power plants, putting its future eggs all in the renewables basket. The public sector NTPC earlier this month told its investors that it planned to instal 60GW of renewable energy capacity in a decade. Indian Oil Corporation chairman Shrikant Vaidya recently said his company was “investing in solar and wind energy in a big way”.

“More than contributing, corporates are driving this space,” said Bose Verghese, head of green initiatives at Infosys, which became carbon neutral last year. “New technologies and innovations (in green energy) carry high risks and high initial costs. (So) corporates can invest in such technologies and help startups and entrepreneurs in this space,” he said.

Startups, too, have flourished in the game, more so with valuations than with actual power supply and net gains. Gurgaon-based ReNew Power, which supplies power from solar and wind farms, entered the unicorn club a few years ago. While investment worth Rs1 lakh crore is estimated to have flowed into this sector in the past three years, this year’s PLI scheme could increase this torrent. US giant First Solar recently announced a Rs5,000 crore investment to set up a PV solar module plant in India, while Hyderabad-based Premier Energies announced an investment of Rs1,200 crore over the next two years. Kolkata-based Vikram Solar and Mumbai-based Waaree Energies are looking at hitting the stock markets to cash in on the surging interest in the sector.

Globally, investments are now redirecting to businesses that are mapped to be high on the environmental and sustainability aspects, referred to as ESG funds. “Globally, many investors have declared that they will not invest in coal-based power generation or in refineries. In renewables, the profits may not be high, but the valuations are going high because investors believe that is the future. And their shareholders are asking them to invest in ESG compliant firms,” said Mishra. A recent study showed 90 per cent of millennial investors will invest only in green businesses.

But, as usual, there are challenges galore in India, particularly the gap between talk and action. For instance, 20GW of solar and wind power projects were auctioned in the past three years, but less than one-fifth of them have been commissioned. Then there is this disconnect between the Centre’s targets and state government priorities. “Many projects awarded by the Centre get stuck as state governments go slow in allotting land,” said an industry observer.

Policies could also do with a firming up. While Prime Minister Narendra Modi has often been emphatic in the government’s push for green energy—the latest target is to achieve 450GW by 2030—no roadmap is in place. This is particularly troubling because there is a conflict between the coal lobby and the international pressure to go carbon zero.

“In a country like India, a combination of solutions is what is required,” said environmentalist and AnantU fellow Ruchie Kothari. “But we definitely do not need any more coal. We may not have a definite strategy to get there, but it is definitely feasible.”

The wind may be blowing in favour of a cleaner, greener India and world. The biggest drawback of solar and wind energy, that they are intermittent, may be solved soon with the availability of better battery storage solutions. It is estimated that solar power, last auctioned at less than 02 a unit in May, could hit a price below 01 by 2030. These factors combined would mean there would be no credible reason left anymore to mine coal and use it to produce electricity.

“Storage, if available at the right cost and quality, is the ideal catalyst for large scale solar adoption in our country,” said Gagan Vermani, CEO and founder of the solar startup MYSUN. “The cost of storage has substantially reduced over the years (and is expected) to make financial viability by 2023.”

A green future beckons, and for India, it is time to walk the talk. Not just because it offers dividends and prosperity. Ambani was not really going hyperbolic when he said new energy was the “most exciting, most challenging and the most purpose-driven mission” he would be pursuing in his life.

More power to you

Technology is proving to be the disruptor in all aspects of life, and the power sector is no exception. Electricity produced in a conventional power plant and distributed through a wired grid could soon become a thing of the past.

Hydrogen

The buzz is the highest when it comes to hydrogen. The power potential of hydrogen was never in doubt, considering its intensive use in steel and fertiliser factories. The challenge was generating it in a viable manner. Electrolysers are used to split water into oxygen and hydrogen, but now it seems this could finally be done in an eco-friendly manner using renewable energy.

Fuel cells

Think those Eveready batteries, but strong enough to power up your home. Fuel cells storing green hydrogen, if tech advances keep pace as promised, could run anything from an off-shore oil rig to buses and cars.

Biomass

Go beyond those compost pits by your neighbourhood RWA. Energy from biomass―referring to organic matter like dead plants and organisms―is produced by harnessing methane, produced by biomass waste decomposition. It already contributes to more than 5 per cent of America’s energy consumption, derived from burning waste as well as from ethanol. The Indian government is seriously looking at using ethanol, made from sugarcane, as an alternative fuel.

Oceans

Ocean waves can produce immense energy, but the jury is still out on this one. The main problems stem from the need for heavy machinery, which may disturb the marine ecological balance, as well as the fact that this energy can be intermittent and would require either supply grid or storage solutions.

Body heat

Not an OTT title. Stockholm railway station uses the body heat of its 2.5 lakh daily users to power a nearby office building. A mall in the US redirects the body heat of its visitors through pipes into a storage tank, which is then used to heat the building in winter.

Cheers to that

Our personal favourite renewable energy source―alcohol waste! In Scotland, many whisky makers redirect grain used in the distilling process to power thousands of homes nearby. All the more reason to have an extra peg!