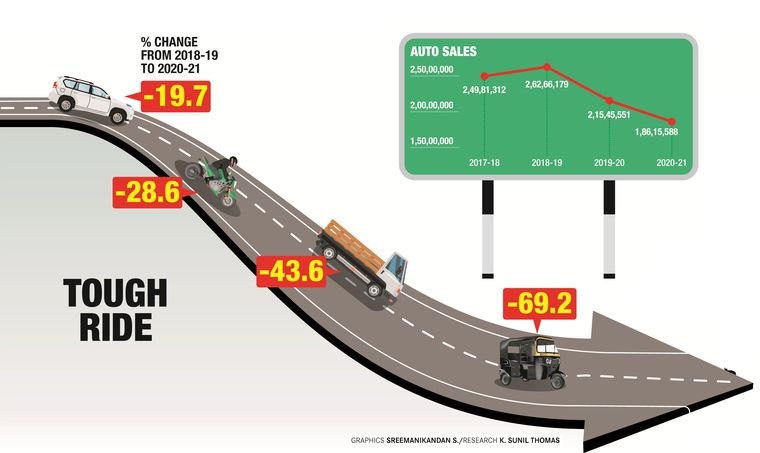

Indian automobile industry’s days of glory had started waning much before the coronavirus hit India, with a protracted slowdown putting the brakes on sales in late 2018 itself. Things have only got worse since then. What is staring at the once-poster boy of India’s post-liberalisation economic engine is a tougher tomorrow, where every day is not just a survival game, but one played to a whole new set of ways and rules.

“India’s auto industry will show a 20 per cent growth this year over last year. But if you compare it with 2018, the last time sales were growing, it is nowhere close,” said Rajeev Chaba, president and managing director of MG Motor India. “Having said that, Covid is unpredictable. Everybody is learning as we speak.”

Sales may go up. In fact, June sales figures showed healthy signs after two months of sales drop. But they are much lower than the boom years of 2012-2018. Still, the auto sector is coming out of the ordeal by fire shaken, stirred and smarter.

Lighter, too. “The automobile industry is glamorous with seven-star infrastructure, slick showrooms, music bands performing and pujas conducted when premium cars are sold. But Covid taught us that it is more important to be agile,” said Vinkesh Gulati, president of the Federation of Automobile Dealers Association.

Just before the pandemic hit, the auto industry’s biggest worry was the impending imposition of BS 6 emission norms, which involved jacked up prices and investment in cleaner technology. But then, when the national lockdown shut down supply chains, factories, showrooms and deliveries overnight, it seemed like the last nail in the coffin. “Automakers took a little time to figure out the risk, but quickly took corrective measures and rose to the challenge…the industry started continuously innovating,” said Rajeev Singh, partner and automotive leader at Deloitte India.

Buying a car or bike is a milestone for most Indians, and traditionally it involves umpteen visits to dealers and haggling over deals. All that went out the window as the industry quickly realised that many consumers were no longer comfortable with physical visits to showrooms. The solution? Digitisation.

“All possible processes were automated,” said Gulati. Manufacturers revamped their websites for immersive experiences, while dealers cut down on showroom sizes and salespeople as well as the use of glossy brochures, instead sending PDF files with all details to customers, following up enquiries on WhatsApp video calls. Premium brands like Mercedes-Benz cut down on inventory with its new direct-to-customer retail model by holding car models centrally. This has reduced the cost to dealers not only for keeping vehicles in showrooms, but also security and showroom rentals.

Digitisation is happening not just to the sale, but also for add-on processes like financing, insurance and registration. “From an average five to eight visits to a showroom before buying, now customers come in just twice or thrice,” said Gulati. “While you had to personally sign 20 papers earlier, now it is only two or so due to automation. Efficiency has gone up.”

“A lot of companies cut down on the number of people visiting corporate offices and plants, with people working from home,” said Singh of Deloitte. “Barring the core team in manufacturing and quality checks, functions like logistics, procurement and marketing, they managed from home.”

Interestingly, many new models have also upped their digital quotient, adding features like touch screens and facilities like live traffic, weather and music streaming through an internet connection on the go. “Features like the Internet of Things (IoT) and GPS systems will be prominent in automobiles,” said Pankaj Tiwari, chief marketing officer of the EV startup Nexzu. That, inadvertently, threw up an unexpected challenge in the process.

Connected to a global supply chain—particularly China—for components and raw materials, India’s auto sector has been left clutching at straws as a global mismatch of supply and demand made many parts unavailable or expensive. Besides the scarcity of steel, aluminium, copper and precious metals, the global semiconductor shortage hit production in Indian plants—top-selling car models have waiting periods running into months.

“Not imagining that consumption would come back so strongly after lockdown, we had allocated our requirement to other industries. But fortunately, or unfortunately, we came back very strongly,” said Vinnie Mehta, director general of the Automotive Component Manufacturers Association, the apex body of auto ancillary makers in the country. “The semiconductor problem is not going to go away very soon, as adding capacity takes two good years,” he said.

The over-dependence on China means that any further localisation would take years. India, for instance, is a large producer of steel. Yet, most of the specialised steel that the auto sector requires is imported from China. “We have the technology in the country and the capability, but sometimes it is cheaper to import from China,” said Mehta. “The volume is not high and hence it is not economical to localise.”

The solution to this, as suggested by a recent insight report by McKinsey, would be to focus more on the export market. “International markets, especially those in Africa that are similar to India, are experiencing a rise in per-capita GDP and reaching the levels at which automotive sales tend to expand significantly. By expanding internationally, Indian automakers will increase growth and sales volume while diversifying risks and reducing demand cyclicality,” said the report.

That last bit is crucial. Buoyed by the ever-increasing sales figures between 2012 and 2018, many manufacturers had invested in expanding their capacities—which have now become an albatross around their necks. While brands like Bajaj and Hyundai have been exporting for long, many others have just started looking at this prospect.

That is not the only pivoting the auto industry has had to deal with. While a mass-market shift to electric vehicles may still take a few years, the sector has realised that changes will be hitting it much more frequently. This ranges from new fuel options like ethanol being pushed by the government to shifts in consumer preferences.

The SUV trend visible before the pandemic has now solidified into an across-the-categories preference at the expense of sedans, the car category conventionally considered the centrepiece in any brand’s offering. Many carmakers got into the compact SUV category initially because market leader Maruti Suzuki did not have a presence in that segment. After the pandemic hit, consumers now see added value in buying an SUV instead of a sedan, as they are more suitable for family mobility, long trips and even weekend getaways. Hyundai’s Creta, for instance, was selling just above 6,000 units a month two years ago; now it is selling nearly 12,000.

“The kind of growth compact SUV has seen is not present in any other segment,” said Gulati. Conscious of the risk of infection, urban users are increasingly buying functional, affordable cars. Used cars are also finding more takers.

With an uncertain future and the march of technology that will require carmakers to adapt quickly, analysts believe that a shakedown and consolidation is inevitable in the auto industry. “Development cost for alternative technologies is very high. Rather than bearing the burden by themselves, alliances would help it get shared between two or three players,” said Singh of Deloitte. “The results can be equally shared—the vehicle (brand) may be separate, but the core technology could be common.”

For all the dramatic makeovers it has been subjected to, India’s auto industry will still be in the doldrums in the foreseeable future. It will take years to achieve real growth, and they will need to be on their toes to deal with faster changes in technology and consumer preferences. Electric vehicles are just waiting for a catalyst to go mainstream, while the spiralling petrol and diesel prices pose another clear and present danger.

“Covid has caused deaths and economic stress, and the fuel prices are going up. But at the same time, there are so many positives, with personal mobility becoming even more important,” said Tarun Garg, director (sales, marketing & service) of Hyundai India. “Vaccination is gathering pace. GDP estimates are still in double digits, which means the economy should come back. The Indian market has shown us that it is very, very resilient, especially if you look at the last two years. We are cautiously optimistic.”