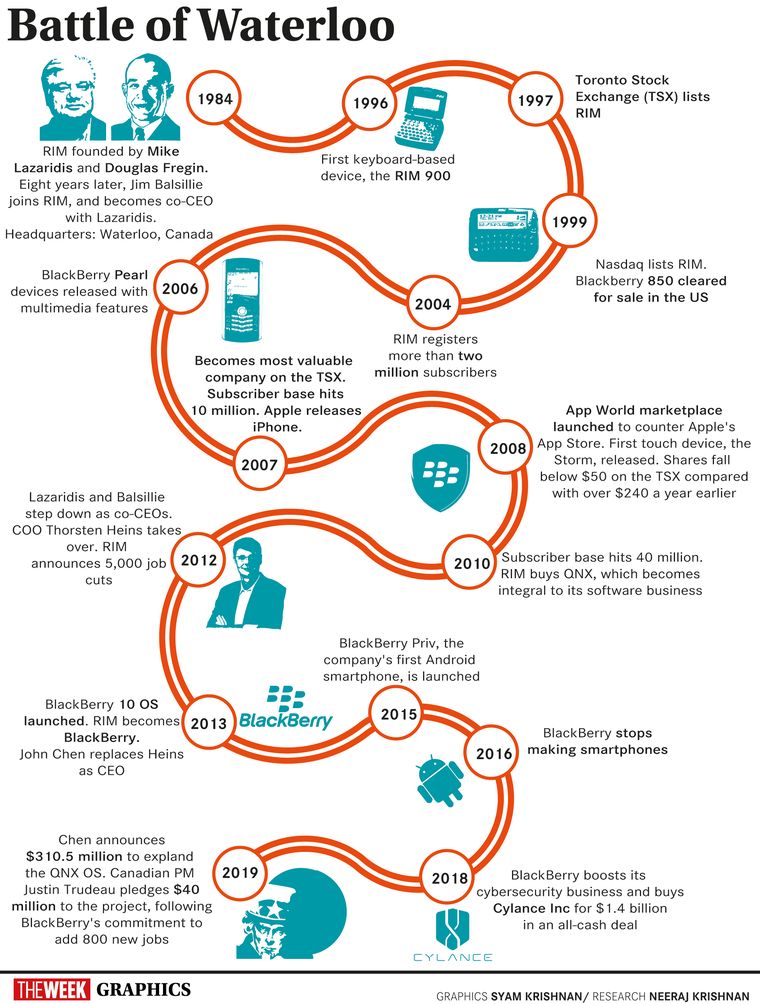

A decade ago, when Barack Obama entered the White House, he wore his faithful companion on his belt: a BlackBerry. He had to pay a price for his brand loyalty. His team took away many of the features he loved, and added security features befitting the phone of the US president. He may not have been allowed to keep the BlackBerry he wanted, but it was a BlackBerry nevertheless.

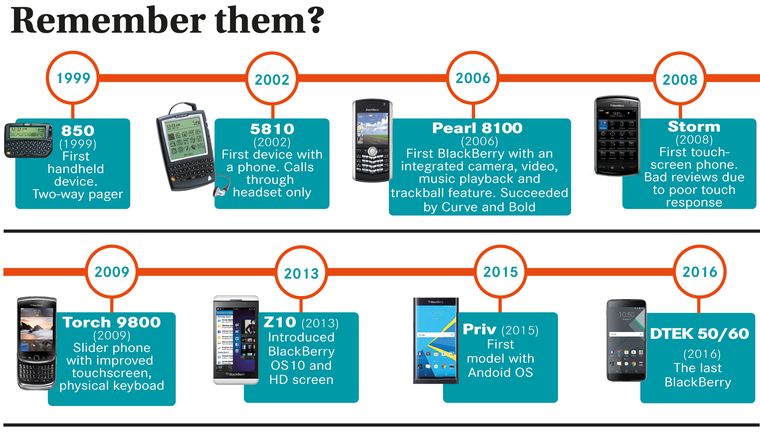

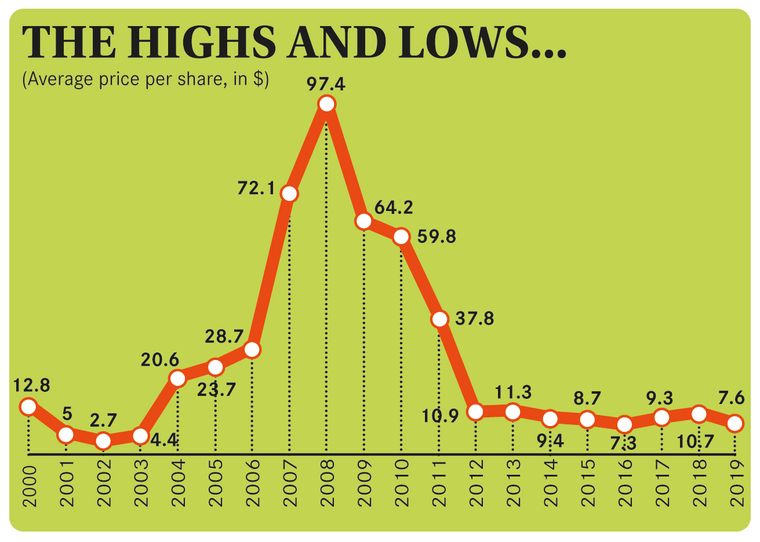

In the heyday of the Curve and the Flip it was a sign of sophistication to whip a BlackBerry out of your pocket. It was the must-have device from Wall Street to Dalal Street. The corporate world was so hooked to the brand that it earned the nickname ‘Crackberry’. But BlackBerry’s Achilles heel was its success. Those at the helm were so blinded by their product’s success that they failed to see the threat from Apple and Google. While the former came up with futuristic phones, the latter opened up the Android platform to other manufacturers who flooded the market with phones big and small. Between the iPhone and Android devices, all pockets were catered to. Apple served the faithful who could afford their expensive phones, while Android offered cheaper, and sometimes even better, alternatives. While all this was happening, BlackBerry shrivelled up thanks to lack of innovation.

At its peak in 2009, BlackBerry, the brand owned by Research in Motion (RIM), had 42.6 per cent of the smartphone market share in the US, Apple had 24.1 per cent, Microsoft 19 per cent and Google just 2.5 per cent. Four years down the line, Android commanded 51.8 per cent market share, Apple 40.6 per cent and BlackBerry 3.8 per cent. In the same year, another behemoth went on its knees, before finally filing for bankruptcy—Kodak.

Once synonymous for capturing memories, Kodak is now a distant memory. While it spent money on developing imaging technology for mobile phones and other digital devices, it held back from developing digital cameras for the fear of obliterating its film business. In 2001, it acquired Ofoto, a photo-sharing site, which could have been the predecessor of Instagram; but they used the site to try and get more people to print images stored in digital albums.

When Netflix approached Blockbuster—the world’s largest home movie video rental service—in 2000 for a potential takeover for $50 million, CEO John Antioco said that it was too niche and that it would not make any money. By 2010, Blockbuster had filed for bankruptcy while Netflix posted revenues worth $2.1 billion. Reportedly, Blockbuster’s final video rental had a telling title—The End is Here.

“Camera phones will be rejected by corporate users”—Mike Lazaridis’s (BlackBerry’s co-founder) famous comment from 2003 shows how blind the BlackBerry board was to changes in technology and consumer behaviour. When asked whether the iPhone would be a threat for BlackBerry going forward, then CEO Jim Balsillie said: “Apple and the iPhone is kind of one more entrant into an already very busy space with lots of choice for consumers. But in terms of a sort of a sea-change for BlackBerry, I would think that is overstating it.” Balsillie and others were proven wrong on September 28, 2016, when BlackBerry stopped designing its own phones. TCL Communication, BB Merah Putih and Optiemus Infracom currently design, manufacture and market BlackBerry phones under a license.

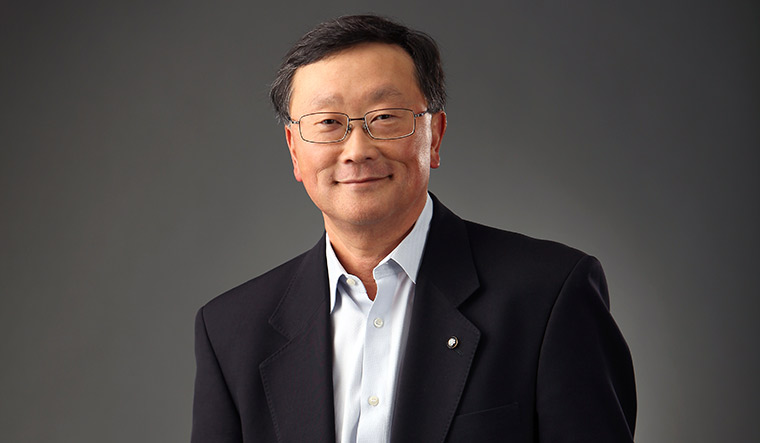

Though Blackberry stopped designing devices in 2016, RIM had begun to see signs of improvement from 2013— when John Chen took over as CEO. In 2013, RIM also officially changed its name from RIM to BlackBerry. While manufacturing smartphones or making them appealing to consumers may not have been BlackBerry’s strongest suit, it sure had a strong foothold when it came to cybersecurity. So, Chen focused on that. And, BlackBerry’s pivot from smartphone manufacturing to a software and services company has been a success story so far and with the way things are shaping up under Chen, the future looks good for BlackBerry.

“Our vision is to have a connected world in which you are safe and your data is yours and to be the world’s leading provider of the most trusted endpoint connectivity technologies. We provide a trusted foundation for the internet of things,” John Chen told THE WEEK.

Chen’s staff echo his vision. “Trust BlackBerry,” says Neelam Sandhu, vice president, business operations, at the office of the CEO. “The company has championed data privacy and never monetised user data. Even today, when the opportunity to monetise user data is vast and easy, we have not taken it. As well, a culture of honesty and integrity is apparent across the company and translates into our customer and partner engagements.”

Sandhu has been working with BlackBerry for over 10 years now, and has seen the transformation first hand. “During my first few years at BlackBerry, we were at our peak of success in the smartphone business,” Sandhu told THE WEEK. “It was when competitors entered the market and brought mobile apps to consumers, which we were not focused on, that we saw the decline in our smartphone market share. Since then we have pivoted from being a hardware company making smartphones, to a software and services company that connects and secures any endpoint. Looking back at the pivot, which was a massive undertaking strategically and operationally, I am in awe of how seamlessly it was done. It would make a great case study for strategic management and leadership programs. The environment we operate in has transformed as well. The market is now saturated with companies focused on ‘connecting and securing the world’ and the industry is recognising that the key—the differentiation—is in software and services, and not hardware, moving forward.”

BlackBerry’s acquisition of Cylance in an all-cash deal is testimony to the fact that things are looking good for the company. BlackBerry is drawing on years of secure communications expertise to position itself as a global cybersecurity leader. BlackBerry software connects and protects over 500 million endpoints today, including cars, drones, the international space station, documents, phones, smart metres, wind turbines, power stations, smart watches and more. Its software is in over 150 million cars on the road today, including Ford, BMW, Mercedes-Benz, Toyota, Honda, Jaguar Land Rover and Subaru. All of the G7, 16 of the G20 and all NATO countries employ BlackBerry services. As far as the corporate world is concerned, BlackBerry software is used by 77 per cent of Fortune 100 companies, 100 per cent of Fortune 100 banks, 100 per cent of Fortune 100 energy companies, 100 per cent of Fortune 100 freight companies and 83 per cent of Fortune 100 insurance companies.

With the world becoming increasingly connected, the main risk is the number of connected things. As the potential number of devices or end points that are connected grows, so does the attack surface area. The scale of this growth also poses a huge risk of manageability to people, which is where artificial intelligence and automated technologies come in. Risks to cybersecurity does not always come from hackers or other state actors. A lot of times it is from unintentional actions by people inside a network. It is in these areas that BlackBerry comes in with its three-and-a-half-decades of experience. BlackBerry’s heritage is security and that is what Chen is betting on: “Deliver the most trusted endpoint communications for the internet of things.”

BlackBerry recently launched BlackBerry Intelligent Security, which assumes a starting point of zero trust and then builds a trust score based on various factors. Those factors include, location, user behaviours—are you left- or right-handed, do you move your mouse in a certain way and so on—job function and more. The solution constantly verifies a user identity, not just at the point of entry into the network or application. They also announced artificial intelligence-based security for cars. The technology is set to transform vehicle safety across a range of capabilities, including predictive software maintenance and cybersecurity threat protection. “Not only do our technology advances provide greater security, they support CIO/IT organisations with the growing and often 24/7 workload they have, and they enable people to connect in new and safe ways that they can trust without a doubt,” says Sandhu.

BlackBerry’s journey may not have been the smoothest, but the software giant is certainly on the trajectory to becoming a global phenomenon again. Where Kodak, Polaroid and Blockbuster failed, BlackBerry became a shining example of making the shift. And the shift seemed effortless, though it may not have been.