LOVE AND VIOLENCE. Faith and betrayal. Goons and gurus. The boom-to-doom saga of brothers Malvinder Mohan Singh and Shivinder Mohan Singh is peppered with all these in good measure. Once the poster boys of India Inc (their pharma company Ranbaxy Laboratories and later ventures Fortis Hospitals and Religare Enterprises had all crossed billion-dollar valuations under their watch), they messed it up big time, as their businesses collapsed in just about a decade. Yet, as the drama plays out at the highest court of the land, it is clearly symptomatic of the many lacunae in India’s corporate regulatory framework.

It all started with money, lots of it. And greed. On the face of it, the amount that is making the headlines—Rs 3,500 crore the brothers are ordered by the court to pay Japanese pharmaceutical company Daiichi Sankyo—is grave enough. But it is loose change in comparison to the Rs 22,500 crore the brothers are said to have blown up since they sold Ranbaxy to Daiichi Sankyo in 2008 and ventured into a blitzkrieg of business expansion into multifarious areas. They lost control of their businesses—some sold to the highest bidder, while some were taken over by lenders. Even their sprawling bungalow in Lutyens Delhi was sold to pay the dues.

“We would now like to fight for our justice and pride... and not for economics,” the brothers said in a joint statement a few months ago. But that was before they turned on each other, even coming to fisticuffs. “He assaulted me. He injured me,” Malvinder alleged in a video he posted online, showing his injuries, last December. A few months earlier, Shivinder had alleged that Malvinder forged his wife Aditi’s signature in some documents, but they kissed and made up after their mother, Nimmi Singh, intervened.

The seeds of disaster were sown right at the time the brothers sold their family business, Ranbaxy, to Daiichi Sankyo. Ranbaxy had made a killing in the generic drug business to become India’s most valuable pharmaceutical company. At that time, Japan was modifying its drug laws to facilitate generic drugs, and acquiring a company specialising in it seemed like a fast way in for Daiichi Sankyo. Also, Daiichi got a drug maker with access to the lucrative American market.

The brothers got solid cash, nearly Rs 10,000 crore, and they promptly ploughed a chunk of it into their new businesses, Fortis (Rs 2,230 crore) and Religare (Rs 1,750 crore), which then kicked off an ambitious acquisition and expansion spree. A similar amount of money (one report puts it at Rs 2,700 crore) was transferred to companies owned by the family of Baba Gurinder Singh Dhillon, head of the Radha Soami Satsang Beas, a Punjab-based spiritual sect that commands lakhs of followers in northern India and abroad. It was only the beginning of a stream of cash flow from the Singhs to Dhillon, who is Nimmi’s cousin. The brothers say Dhillon was like a father to them, especially after the death of their own, Parvinder Singh, in 1999. On Dhillon’s advice, they appointed Sunil Godhwani as the head of Religare Enterprises.

At first, all seemed hunky-dory. Fortis grew rapidly—once even crossing Apollo to become India’s biggest hospital chain—and Religare’s multiple wings performed well. Dhillon, on his part, invested in real estate, cashing in on the spiralling land rates in Delhi’s satellite towns in 2010 and 2011. More money flowed in to the many companies floated by him from the Singhs or through a complex maze of their companies and subsidiaries.

Then, disaster struck. As the real estate bubble burst in 2011, Dhillon’s investments came a cropper, leaving him with huge debt. The rapid expansion of Fortis and Religare, all funded by massive loans, suddenly came back to bite the Singhs as the slowdown took hold. “Appropriate risk, appropriate growth, transparency in financial dealings and having an independent board which could question their actions were all steps that could have contained their greed,” said N. Chandramouli, CEO of the business consultancy TRA Research. A vicious cycle of mortgaging assets and shares to pay off initial debt plunged them deeper into the debt hole. According to information with the Registrar of Companies, assets worth more than Rs 15,000 crore were pledged, many of them possibly to pay off earlier debts.

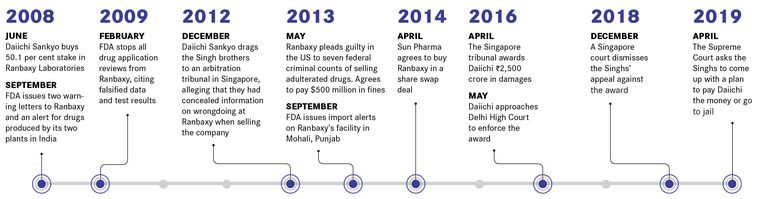

To make matters worse, Daiichi Sankyo alleged that the brothers did not disclose that the US government was investigating Ranbaxy when it acquired the company in 2008. A few months after the deal, the Federal Drug Administration, America’s powerful drug regulator, banned medicines from two Ranbaxy plants in India and launched an investigation into the company’s practices. In 2014, Daiichi sold Ranbaxy to Sun Pharma. In 2016, a Singapore tribunal directed the Singhs to pay about Rs 2,500 crore to Daiichi Sankyo (the total amount now is around Rs 3,500 crore, including interest and legal fees). The brothers, however, delayed the payment, prolonging the wrangling and setting the stage for the denouement at the Supreme Court.

In between, the Singhs lost control of both Religare (taken over by equity investors) and Fortis (bought by Malaysia’s IHH Healthcare last year). A month ago, in a complaint to the economic offences wing of the Delhi Police, Malvinder accused his brother, Dhillon and Godhwani of criminal conspiracy, cheating and fraud. He claimed the outstanding from Dhillon was Rs 8,646 crore as of 2016, and that he was threatened by Shivinder every time he asked for it. “Shivinder initiated these actions and permitted siphoning and malfeasance of funds with the ulterior motive of gaining control of the seat of the spiritual head of Radha Soami Satsang Beas, which was promised to him by Dhillon in lieu of the financial gains,” he said. Shivinder, however, said the fraud happened while Malvinder was running the company. Shivinder had renounced his corporate posts to join the ashram. He returned in 2015.

“It is not about individual honour... it doesn’t look good for the country’s honour,” said the Supreme Court while hearing the case against the Singhs. Corporate India’s recent track record when it comes to payments has not been very good. It begets the question, what needs to be done? “Corporate laws are well formed, but poorly implemented,” said Chandramouli. “It is difficult for those erred against to get justice. In a world which works solely on trust, it is important that transgressors of trust be taken to task.”