There are now over one million cases of COVID-19 globally. Nations everywhere are busy trying to contain the COVID-19 pandemic, while scientists and epidemiologists seek out the pattern of the disease’s spread, looking for preventative measures against it and a remedy if any exists.

While coronaviruses have been recorded before, the strain that causes COVID-19—SARS-CoV-2—is new. Of all the possibilities for the virus’s origin, its transmission from a wild animal to a human being cannot be ruled out. The cause for this can be traced to illicit wildlife trade, for which all nations, directly or indirectly, are responsible.

At present, the epicentre of the outbreak is alleged to be a wet market in Wuhan, China. Here, pangolins normally seen in South East Asia were traded and sold for human consumption. Recent research suggests that the pangolin served as the link between bats, which are known to carry coronaviruses, and human beings.

Bats, pangolins and human beings are not natural co-habitants, as all but the latter are wild. A species barrier prevents the transmission of microorganism between wild and non-wild. But, human beings are known to disrupt ecosystems, cut forests and eat wildlife. The presence of Malayan Pangolins (also known as Sunda or Javan Pangolins) in a market in Wuhan, China, strongly points towards the real culprit behind the genesis of the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic—illegal wildlife trade and trafficking.

Like many other wild species, pangolins are heavily poached and exploited, despite being protected animals. Malayan pangolins are hunted for their skin, scales, and meat for use in traditional oriental medicine. All species of pangolin are included in CITES Appendix I, which means that international commercial trade is prohibited.

Illicit Wildlife Trade and Trafficking

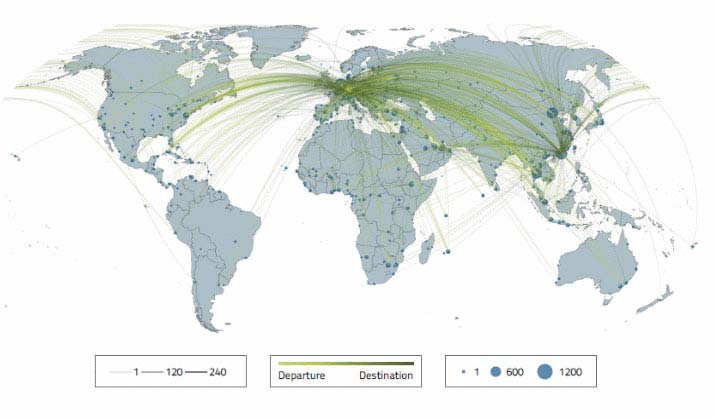

As per the World Customs Organization’s Illicit Trade Report, in 2018, customs administrations from 47 countries reported cases of wildlife smuggling amounting to 2,727 seizures of flora and fauna. Traffickers were discovered smuggling 59,150 pieces and 3,60,495.6 kilograms of various flora and fauna. Nearly all countries were implicated as a known or intended origin, transit or destination point. This illustrates the gravity of the manmade damage the world has to deal with in the decades to come.

Studies on the movement of wildlife contraband depict the demand and supply pattern. Being rich in biodiversity, the Indian subcontinent, Africa and South America are found to be the most vulnerable regions for wildlife crimes and trafficking. In most cases, China is identified as the destination. Rhino horns, ivory, live pangolins and its scales, turtles and tortoises, snakes and snake skin, mongoose, sea horses and sea cucumber, crocodile skin, porcupines and so on are trafficked in substantial quantity from various natural habitats across the world.

It would be interesting to scrutinize the trafficking attempts of some indicative species from India. During the last ten years, Indian Customs seized 27 python skins, 102 pieces of rat snake skins, 283 pieces of sea snake skin and seven pieces of water snake skin from various ports and airports. Further, 121 hand bags of snake skin origin were also seized during this period. Attempts to smuggle out 19.13 kg of dried snakes were also prevented effectively.

The pattern of smuggling of another indicative species, the star tortoise (Geochelone elegans; CITES: Appendix II) was studied over a period of ten years. Live turtles and tortoises were found to be illegally trafficked on both domestic and international routes, to be kept as pets or used in medicine or as food. Their shells are used in the manufacture of ornaments, frame of spectacles, cigarette holders, musical instruments and art pieces. The maximum number of seizures by Indian Customs was reported at Mumbai International Airport and the seized turtles were destined to wet and dry markets in Thailand, Malaysia and China.

Being rich in biodiversity, the Indian subcontinent, Africa and South America are found to be the most vulnerable regions for wildlife crimes and trafficking.

Being rich in biodiversity, the Indian subcontinent, Africa and South America are found to be the most vulnerable regions for wildlife crimes and trafficking.

It is an open secret that many Wuhan-type wet and dry markets are running in China, Thailand and Vietnam, where there is strong demand for exotic wildlife articles. In China, domestic wildlife farming itself is assessed as a billion-dollar industry. The rich and privileged class is the largest consumer of wildlife products, thanks to the superstitions surrounding traditional Chinese medicine and the false pride associated with the ownership of certain wildlife products. Articles like rhino horn, pangolin scales and tiger bones are used to make traditional medicines, used as potential aphrodisiac and as ingredients in body building tonics.

These Oriental superstitions are proven incorrect by scientific scrutiny. Chemical analyses indicate that rhino horns and pangolin scales are made of keratin (a protein which makes up hair and nails) which has no specific medicinal value. However, false notions are hard to crack as can be seen from the reports of growing demand from Chinese wildlife markets for rhino horn extracts for the treatment of COVID-19. Bearing in mind that rhinoceros are not seen in China any more, the pressure would be on wildlife mafia in the neighbouring countries to procure them. This is an urgent and explicit red flag for wildlife and customs authorities in India.

Wet markets: A virus mixing bowl

A wet market is a place where live meat, fish and other marine animal products are sold. As the name denote, these markets are always wet. Water overflows from the tubs where live sea animals are kept, floors turn red with the warm blood of freshly-slaughtered animals and parts of alimentary tracts of fish and reptiles are scattered on the walkway. Turtles and snakes crawl over each other before they are cut into pieces.

The emergence of COVID-19 and the role of Wuhan market is still under investigation.

The emergence of COVID-19 and the role of Wuhan market is still under investigation.

Chinese, Vietnamese, Thai and Myanmarese wet markets are infamous for selling wildlife meat and other numerous articles of wild origin. In a Wuhan market-like scenario, various wild species and articles thereof are assembled for exhibiting to the consumers.

Live animals are kept in cages which are stacked one above other. Thus, a scene where a cage with bats or snakes on the top and cages containing turtles, civets, ducks, porcupine and pangolins stalked below them are common in these markets. The excreta and fluids from the species kept at the top will fall on those creatures kept below and entire stock act as a ‘natural mixing bowl’ that provides the virus an opportunity to jump from one organism to another.

In such a crowded and stressful condition, the immune response of these organisms goes down, virus-shedding escalates and susceptible animals become infected and further shed the virus. While handling the meat or the live animal, human beings contract the virus. Inside the human body, the virus undergoes a ‘mutation’ and can subsequently develop the capacity to transmit from one person to another, causing pandemics of the current magnitude.

The emergence of COVID-19 and the role of Wuhan market is still under investigation. However the 2003 outbreak of SARS CoV -1 was ultimately traced back to masked palm civets (Paguma larvata) and raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides) traded in a Shenzhen wet market in China (Clin. Microbiol. Rev.2006). Chinese authorities had temporarily prohibited operation of all the wet markets in 2003, but these were later reopened.

Why do Wuhan-like markets exist?

Wildlife farming, consumption of wild meat and trade in China has historical reasons like famine and poverty. Over a period of time it evolved as a culture and tradition. This led to huge demand for game meat and the domestic production was inadequate to meet the market requirement. International wildlife trafficking provided safe passages for wildlife articles, meat, sometime live animals to destination countries including China. Origin ecosystems like South Asian region (India, Bangladesh, Sri Lanka), Brazil and African Continent could not realize the far reaching implications for a considerable period of time. Though poaching and trafficking of wildlife is viewed as a heinous crime in these regions, such offences were not often deemed serious and weaker punitive measures were awarded. Thus lack of public interest and weaker enforcement led to huge hunting and trafficking of wildlife contraband in the last two decades, which allowed Wuhan-like markets to flourish.

What happens after the markets are closed?

Trafficking of wildlife is a market-oriented and dynamic, illicit business. Soon after the closure of Wuhan-like markets in China in January 2020, online sales of wildlife articles are reported to be booming. The post-SARS closure of wet markets in 2003 was also short-lived, due to pressure from the powerful wildlife industry in China. Adding to the wet market culture of cutting and eating live animals, decorating houses with animal products; the recent addition to this series is the crazy pet industry. Reptiles, turtles, wild lizards and other exotics species are fostered as ‘new age pets’ in many developed and developing countries. Close contact with these ‘pets’ offers opportunity for viruses like thye coronavirus to jump and cross species barriers. Unless strictly prohibited, the wild pet culture will be the next epidemic bomb.

The rich and powerful and their superstitions act as the driving forces for nurturing online and offline wildlife markets. Poor act as first line poachers who risk their health and lives to hunt and traffic these species across the borders. The effort of customs and wildlife enforcement agencies unearths only the tip of the iceberg. Actual rate of wildlife crime and trafficking from south Asian countries and Africa could not be estimated. The more the events of man-wildlife contact, the more the emergence of a novel epidemic. David Quammen in his book, Spillover: Animal Infections and the Next Human Pandemic, notes that “You go into a forest and you shake the trees—literally and figuratively—and viruses fall out."

Novel concerns and the way ahead

The role of public, NGOs, enforcement agencies and international organizations cannot be overemphasized in prevention of wildlife crimes.

The role of public, NGOs, enforcement agencies and international organizations cannot be overemphasized in prevention of wildlife crimes.

In 2010, Indian Customs had seized over 10,000 ‘read-eared turtles’ that were trafficked from China to India through the Kolkata International Airport. On further investigation it was found that the red-eared turtle species was classified as one of the most invasive species on the earth by the IUCN. The virus and microbial load they would have carried to the Indian ecosystem was another concern, though not studied. The role of public, NGOs, enforcement agencies and international organizations cannot be overemphasized in prevention of wildlife crimes. Mass awareness, huge public funding and strict policies along with globally co-ordinated enforcement are the keys to containing this menace and preventing another pandemic like COVID-19.

Dr Anees Cherkunnath IRS

Dr Anees Cherkunnath IRS

The opinions expressed in this article do not purport to reflect the opinions or views of THE WEEK. Views expressed above are the author's own.

Dr Anees Cherkunnath is an IRS officer in Indian Customs. He holds a PhD in Veterinary Science