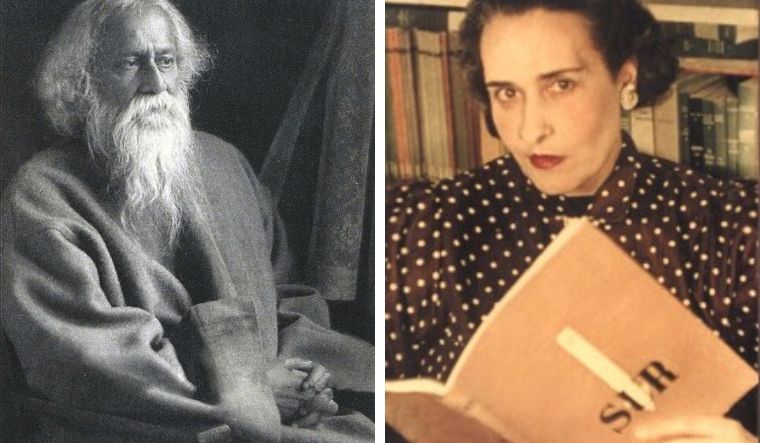

After reading the review of the film Thinking of Him, which explores the relationship between Rabindranath Tagore and Argentine writer Victoria Ocampo, many are curious to know if there was a carnal part to the platonic love.

Putting it the Argentine way, ‘It is complicated’.

The most frequently used word in Argentine vocabulary is ‘complicado’ (complicated). You may ask an Argentine about his country, politics, economy, debt, marriage, love, weather or the world. ‘Complicado Che’ is how they start their response and explanation. ‘Che’ is an endearing way of saying ‘friend’ in Argentina.

When it comes to the Tagore-Ocampo relationship, here is the first complication:

The ‘heroine’ drew a line; the ‘hero’ did not cross it. But he was tempted… he tried—just a touch… without crossing the line.

This is what Ocampo says in her autobiography: “One afternoon, as I came into his room while he was writing, I leaned towards the page which was on the table. Without lifting his head towards me he stretched his arm, and in the same way as one gets hold of a fruit on a branch, he placed his hand on one of my breasts. I felt a kind of shudder of withdrawal like a horse whom his master strokes when he is not expecting it. The animal cried at once within me. Another person who lives inside me warned the animal, ‘ be calm… fool’ It is just a gesture of pagan tenderness. The hand left the branch after that almost incorporeal caress. But he never did it again. Every day he kissed me on the forehead or the cheek and took one of my arms, saying “such cool arms”.

This was the farthest Tagore went physical. Ocampo's graceful and quiet but firm and cold non-response stopped him at this point.

Ocampo described her emotion for Tagore as a great “love tenderness” (amour de tendresse). A love into which nothing entered except the spiritual.Tagore has, of course, talked about his love and longing in poetic but subtle and suggestive ways in his notes and letters to her as well as poems.

More complications:

Tagore’s secretary Leonard Elmhirst (who accompanied Tagore in the South America tour) went beyond Tagore in exploration. He tried to kiss Ocampo when they were in the car. She slapped him and banged the car door so hard that the sound ‘shook the whole city’. Thereafter he apologised. She accepted it and did not make any fuss afterwards.

In her autobiography, Ocampo says that Elmhirst was infatuated by her. She had also felt a bit of attraction to him. That’s why she kept up contact with him for many years and had visited him in England. She even dedicated her book on Tagore to Elmhirst, calling him ‘a friend, friend of Tagore and friend of India’.

Ocampo had confessed to Elmhirst the story of her unhappy marriage in 1912 and how her husband treated her like a “conquered land”. She found a secret lover five months after her wedding. It was Julian Martinez, one of her cousins. Since divorce was not permitted and she did not want to upset her family, she continued to live in the same house with her husband but in separate bedrooms. In 1922, she moved out and lived separately on her own in an apartment. Neither Elmhirst nor Tagore knew about her secret lover. If they had known, those accidents might not have happened.

Tagore mistook Ocampo’s excessive devotion for something more. At the time of Tagore’s visit, Ocampo was in a state of transition after the break up with her husband and the strains of keeping the secrecy of her love affairs with her cousin. The society had thrown cold water on her aspiration to become a woman writer. At the same time she did not want to upset her family by open rebellion. She wanted to bring Tagore to stay in the large mansion of her parents but they refused. At this time of mental turmoil, she looked up to Tagore as a Guru from the East who might illuminate her spirit and reveal a new path for her. This is what made her to show extraordinary and explicit expression of her excessive ardour to Tagore.

But the old widower poet mistook Ocampo’s devotion as inviting signals. He thought, “he had received ‘a woman’s love’, the kind of love he had been hoping for a long time to ‘deserve’ the love that alleviates a man’s inner loneliness and is like a’ supply of water’ in his journey across a desert.” This was reflected in his poem Shesh Basanth (the last spring) which he wrote on November 21 during his stay as the guest of Ocampo.

While walking on my solitary way

I met you at the dusk of nightfall

I was about to ask you take my hand

When I gazed at your face and was afraid.

For I saw there the glow of the fire that lay asleep

In the deep of your heart’s dark silence

The old man did not fail to notice the tension of attraction between Ocampo and Elmhirst. How did he deal with it? He teased Elmhirst saying that he should marry her and bring her to Shantiniketan. He said this with his knowledge that Elmhirst was already engaged and soon to be married (actually in April 1925) to Dorothy, an American heiress. He told Ocampo that Elmhirst was in love with her. Mischief in the mind of the mystic poet?

For Ocampo, the explorations by Tagore and Elmhirst did not come as a shock. She was used to such advances. Since she was living as a single, separated and independent young and beautiful woman with rich inheritance, many men were tempted. A Spanish poet Ortega y Gasset, older than her, tried to seduce her couple of years earlier but she rebuffed him decisively. But she liked him as a poet and kept in literary contact with him. Later, she had many affairs with older and younger men. One thing was clear. She did not want to live with the label of someone’s wife or lover. She took her destiny in her own hands. She did not let others to mess with her life beyond a line she drew. Perhaps this is the main reason she declined the repeated invitation of Tagore to her to visit Shantiniketan. She did not imagine herself to be like the western ladies Nivedita and Mirabehn who had dedicated their lives to serve Vivekananda and Gandhi in India. Ocampo wrote, ‘I cannot envy them because I know that my Dharma would not have made their path as mine.

Of course, before and after Ocampo, many foreign and Indian women were attracted to Tagore and he was also interested in them. But it seems that Ocampo remained as the main muse for Tagore in the 17 years from 1925 to his death in 1941. Besides dedicating the ‘Purabi’ poems to her, Tagore is said to have written many other poems and stories as well as done paintings alluding to Ocampo.

Ocampo is credited with uncovering Tagore’s painting talents. It was she who saw his doodlings in Buenos Aires and encouraged him to paint more seriously. She organised the first exihibition of Tagore’s paintings in May 1930 in Paris at the Galerie Pigalle by spending her own money, organising a party and using her contacts. Encouraged by the Parisian reception, he started painting and holding more exhibitions thereafter.

For those curious to delve deeper, there is plenty of information in Ketaki Kushari Dyson’s book In Your Blossoming Flower Garden. She has done detailed analysis of words, actions and circumstances of the Tagore-Ocampo encounter and has written objectively.

For Argentine amigos, the Tagore- Ocampo relationship is like Tango dance— the man and woman touch each other’s bodies 'creating sparks' but 'without getting burnt'.

The author is an expert in Latin American affairs