T he Saxenas were a regular middle class family of four in Lucknow—the father an advocate, mother a homemaker and two sons in class IX and XI. Then, in May, the second wave of Covid-19 took away the mother and destroyed their happiness. The pandemic isolated them, first because the family was tested positive, and later, because no one was meeting anyone anyway. They tried resuming their normal lives online. But something had snapped. There was just nowhere to go, no friends who could lend a shoulder or share a joke. A few weeks later, the Saxenas were back in hospital; the elder son had attempted suicide. He survived. The family is now going to counselling, and hoping to make it back to some semblance of normalcy.

Almost everyone in the country by now has had a brush with the pandemic, be it getting infected, losing a loved one or taking financial hits. And almost everyone has encountered someone who has had some sort of mental problem because of the pandemic, be it anxiety, anger, depression, losing the will to live or actually trying to take their lives. Or even kill someone.

It is almost as if the nation is reeling under a collective post-traumatic stress disorder. A young doctor who was inundated with serious cases and had to make difficult triaging decisions ended up a nervous wreck herself. Wracked with guilt at having to select which patients to prioritise, given limited facilities, she first had sleeplessness, then crying spells and, then, totally lost the will to work. She reached out for psychiatric help and took a break from work—a guilt-ridden choice given the need for doctors. But she was brought back from the brink. Then there was the grandfather in Karnataka, who saw his entire family perish one after another, till just he and a grandson remained. Troubled with survivor's guilt—he could not understand why he was alive while the younger ones died—he tried taking his life. He survived, and is now trying hard to get back to his normal self.

Manisha Sharma, 35, was a cheery, chirpy woman till April, when she got Covid. Shut in her home, the only news she got from the outside world was of near and dear ones dying. Within weeks of her recovery, Sharma realised she was in bigger trouble, as she was not able to perform even everyday tasks without having panic attacks. The mobile ringing in the morning would bring a knot to her stomach; she still associates morning calls with bad news. She is on anti-anxiety medication, and thought she was improving till she heard of a colleague dying of cancer, and she experienced another meltdown. “I am recovering, but I can never be certain when the panic attacks will return,” she says. She also developed an aversion to closed rooms and hates being alone. All these bring back memories of her isolation days, and the helplessness she battled then.

The mental health problems during the two lockdowns were different. Last year, the trigger was job loss and the suddenness of being cramped into limited space. Home was no longer the best place. In fact, one couple, which decided to return to the joint family during the first lockdown, found the adjustment so difficult that the wife became suicidal.

This year, it was the sheer scale of death and devastation that triggered mental health issues. Add to it Covid protocols for funerals and mourning, which did not allow people to meet and share grief. For many, there was no closure, which is what these functions are largely about.

The brave new world that has once again returned to work, has brought with it a whole set of demons. There is mental baggage from the past, adding to the fears of the uncertainties ahead. Will there be a third wave? Is there a job after my graduation? Those with existing mental health issues have had it even worse. Already, several medical groups, including Alzheimer's Disease International, have flagged the issue that a Covid-19 infection could accelerate the rate of dementia in a patient. What this means is that even after the pandemic is over, the mental health burden will linger.

Can the workplace be empathetic to mental health? The silver lining is that conversations about mental health have started, people are realising it is no longer a shameful and taboo subject, notes Debanjan Banerjee, geriatric psychiatrist at NIMHANS, Bengaluru. “The discourse on mental health was long pending, the pandemic has brought it out in the open at least,” he says. One sees rays of hope in certain decisions of the judiciary. For instance, the Gujarat High Court recently said that depression can be classified as a serious illness in the context of the pandemic. It was ruling on the case of an engineering student whose admission was cancelled as he had not written his exams and earned the requisite credits. The student said that he had “severe depressive episodes with suicidal ideation” from January 2020, and his condition worsened by June 2020; he could not write the exams.

The Supreme Court recently told the government to consider Covid patients who had committed suicide also as Covid deaths. The bench of Justices M.R. Shah and A.S. Bopanna, said: “If the government is paying compensation to a particular class (of persons who died due to Covid), what about those who died by suicide because they were suffering from the illness? Ultimately, we have to consider the suffering of the people. Nobody will commit suicide without reason.”

For once, planners and medical experts had factored mental health during the pandemic into their planning right at the start. The Telemedicine Practice Guidelines 2020, in which the home patient treatment protocol included patients being repeatedly asked to discuss their fears and anxieties, was a welcome and proactive step. Many people reached out to helplines and counselling through telemedicine. “Last year itself, NIMHANS, in association with the Centre, had predicted there would be a rise in mental health issues because of the pandemic, and gave guidelines to all psychiatrists on identification and treatment for all groups, from paediatrics to geriatrics,” says Mayurnath Reddy, consultant psychiatrist with Yashoda Hospitals, Hyderabad.

In his practice, he has noted an increase in patients across all levels of severity and age groups. “There is a 20 to 30 per cent rise across all groups, and up to a 10 per cent rise in severe cases,” he says. The reasons are both a rising mental health pandemic and a recognition for treatment. The most common cases are panic attacks, in which a patient can, within the span of 15 minutes, go from normal to having palpitations and restlessness and a sudden feeling that she might even die. There are anxiety disorders and depression cases, and an increasing number of digital addiction cases, especially among the youth. Digital addiction manifests itself when the person shows symptoms of sleeplessness, anger and violence. Long hours of online existence during the pandemic resulted in this side effect.

Just how important timely counselling is cannot be better highlighted than by the experiences of Sarla Samaiya, 68, in Bhopal, who lost her husband and two sons to the pandemic this May. Samaiya may not be highly educated, but she knows that while her sons Subodh, 47, and Saurabh, 36, succumbed to the infection, her husband, Satish Kunar, 71, died because he lost the will to live after his sons' deaths. They all died within ten days of each other. “If he could have spoken to Dr Rahul (clinical psychologist Rahul Sharma) he might have survived. He kept pulling out his mask and refused to eat and drink after he learnt about our sons,” she says. She, too, was admitted at the Hamidia Hospital, where Sharma went to talk to patients. “When I first met her, all her grief and helplessness were bottled up. I listened to her, allowing her to express her feelings. On my third visit, she said that had her husband met me, he might have survived,” says the psychologist. He noted that while she was suffering from PTSD, she might not require major psychiatric intervention now.

Then there is Rakshina Khan, 38, who recalls the terrible times in hospital, for 50 days. Her oxygen mask may continue for more weeks, too. As she battled the disease, she worried about her children back home. In the hospital, there was death everywhere. One day, a patient jumped from the sixth floor ICU to his death. She used to feel so lonely that she would give tips to the hospital staff to talk with her. Then, Sharma visited her. “I could talk to him about everything, joys and sorrows and he listened to me,” she recalls. “He was clad in a PPE kit, but he would pat my head.” That tiny human touch, perhaps, saved her. “She was in need of emotional first aid and simply allowing her to speak out, feel comfortable and being attentive were a big boost to Rakshina’s energy levels and her will to beat her health challenges,” says Sharma.

For every person who was able to get timely help, however, there are many others who could not. Despite conversations having started, recognising a case as one needing psychiatric intervention escapes most people, even doctors. Reddy recalls how a patient came to him. She had repeated breathlessness and palpitations. The doctors did a battery of tests, but simply did not think of a psychiatric assessment. It was a friend, who had had similar issues, who recognised the need and suggested she meet Reddy.

If doctors themselves do not always recognise a case, expecting workplace empathy is a tall order at this stage. However, given the predictions of a rise in mental health problems over the next few years, triggered by the unsettling situation the pandemic has created, there is a great need for sensitising people about the issue.

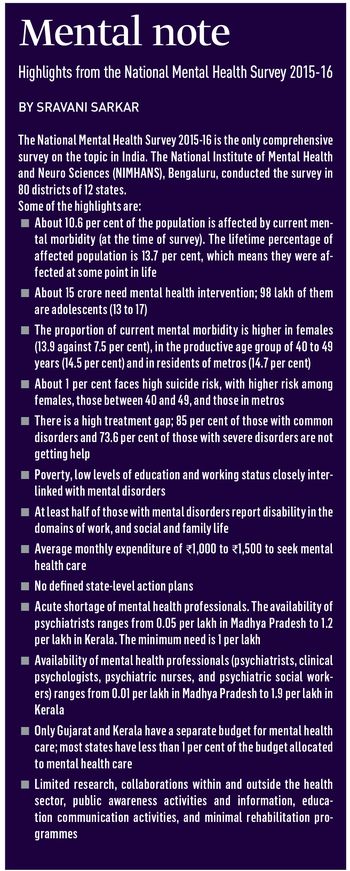

Then, there is this great shortage of mental health professionals in the country. As the most comprehensive study on mental health in India by NIMHANS shows (see box), there is a minimum need of one mental health professional per lakh of the population, but on an average, there is one psychiatrist for every 10 lakh Indians. The distribution, too, is not uniform, with some states like Madhya Pradesh having as low as .05 per cent psychiatrists per lakh population, while Kerala being better at 1.2.

While addressing this shortage is another matter entirely, experts say that the important thing at present is to ensure that available facilities are maximised. Banerjee notes that there are many people who are in the “pre-psychiatric stage” and reaching out to them could help stem their progress into a stage where they may require severe treatment and medication. “It is like identifying people who are predisposed to diabetes, and getting them to make lifestyle changes so that they either do not get diabetes, or can at least delay its onset,” he explains. And how exactly does one identify prospective cases? It often comes up at general screenings at primary and secondary health care sectors, just as one checks for anaemia and other conditions. “One or two simple questions to ask the patient’s state of mind, or an inquiry about their families can reveal a lot of information,” says Banerjee.

Also, target groups can be reached out to. People who have been in isolation for long periods are one such group, those who have had tragic losses another. Students who are anxious about their future after graduation are yet another. “There will always be a shortage of resources,” says Banerjee. “But if we have to tackle the rising mental health issues in the wake of the pandemic, we just have to optimise what we have.”