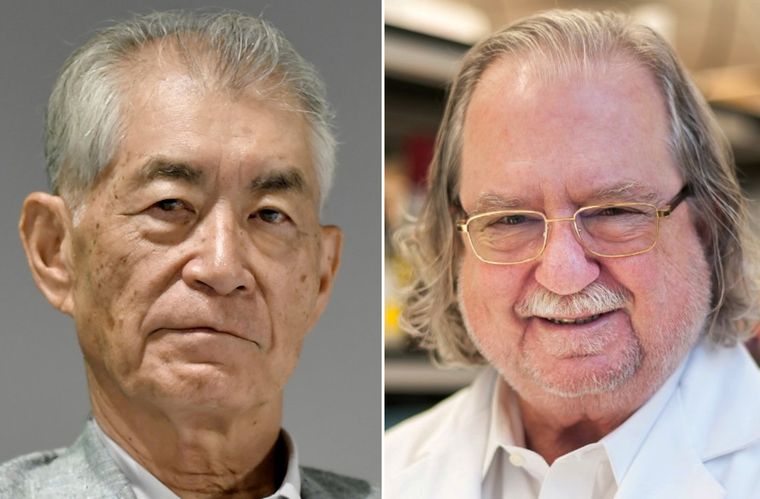

The Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for 2018 was awarded to James P. Allison of the United States and Tasuku Honjo of Japan for their work on boosting the body’s immune system to attack cancer. Immunotherapy, as this approach is referred to, is now one of the hottest areas of cancer research. Their research has led to the development of a form of immunotherapy, called checkpoint inhibitors, which can release the brakes on the immune system, blocking proteins that stop it from attacking cancer cells.

Cells of the immune system, called T-cells, patrol the body constantly for signs of disease or infection. When they encounter another cell, they probe certain proteins on its surface, which serve as insignia of the cell’s identity. If the proteins indicate the cell is normal, the T-cell leaves it alone. If the proteins suggest the cell is cancerous, the T-cell would lead an attack against it. Once T-cells initiate an attack, the immune system releases a series of additional molecules to prevent the attack from damaging normal tissues in the body. These molecules are known as immune checkpoints.

Tumour cells often wear proteins that reveal the cells’ cancerous nature. But, sometimes they commit an identity theft, dressing themselves in proteins of normal cells. Recent research has shown that cancer cells often utilise immune-checkpoint molecules to suppress and evade an immune-system attack. T-cells, deceived by these normal-looking proteins, may allow the tumour cell to go unmolested. Checkpoint inhibitors block normal proteins on cancer cells, or the proteins on T-cells that respond to them. The result is to remove the blinders that prevented T-cells from recognising cancerous cells.

Dr Allison identified a checkpoint called CTLA-4 and Dr Honjo found a different one, called PD-1. These discoveries made it possible to develop drugs that would set the T-cells free to fight cancer. The checkpoint inhibitors now on the market are used for treatment of cancer in lungs, kidney, bladder, head and neck; for the aggressive skin cancer melanoma, and for Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The first checkpoint inhibitor drugs to be approved were ipilimumab (brand name Yervoy), nivolumab (Opdivo) and pembrolizumab (Keytruda). Ipilimumab is based on the checkpoint CTLA-4, and the other drugs work on PD-1.

“Immunotherapy has been an idea for more than 100 years to treat cancer,” says Dr Carl June of University of Pennsylvania, the pioneer behind the breakthrough therapy for cancer using genetically modified CAR-T cells. “But, we did not have tools that were good enough to make it work. Now we have these, through years of basic research on the immune system and ways to modify genes.”

Named Kymriah by Novartis, the therapy using CAR-T cells was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2017, for treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in children and young adults up to 25 years, who did not respond to other treatments. In this form of immunotherapy, immune cells from the patients are removed and then genetically altered to help them fight cancer. These re-engineered cells are then multiplied in the laboratory and dripped, like a transfusion, back into the patient.

When discussing immune system and related therapies, vaccines cannot be far behind. However, in cancer treatment, vaccines have not been very successful. But, recently, research teams at Stanford University, headed by Dr Ronald Levy and Dr Joseph Wu, published results on two separate approaches.

Dr Levy’s team injected minute amounts of two immune-stimulating agents directly into solid tumours in mice and found that this could eliminate all traces of cancer, including distant, untreated metastases. Meanwhile, Dr Wu’s team is using pluripotent stem cells to create a vaccine that makes mice immune to breast, lung and skin cancers.

Unlike childhood vaccines, which are aimed at preventing diseases like measles and mumps, cancer vaccines are aimed at treating the disease once the person has it. The idea is to prompt the immune system to attack the cancer cells by presenting it with some piece of the cancer. The only vaccine approved specifically to treat cancer is Provenge, for prostate cancer.

Earlier, the standard care for cancer included surgery, radiation, chemotherapy and hormonal treatments. However, with the discovery of new drugs and research on experimental approaches, cancer patients now have treatment options ranging from monoclonal antibodies, targeted therapies, combination therapies, personalised therapy, cell therapy and immunotherapy.

Dr Ravi Vij, professor of oncology, Washington University School of Medicine, says that Rituxan (first monoclonal antibody therapy), Gleevec (first tyrosine kinase inhibitor therapy) and immunotherapy (check-point inhibitors and CAR-T cells) have been instrumental in changing cancer treatment.

Monoclonal antibodies used in cancer treatment are designed in a lab to target certain antigens—foreign substances in the body—that live on the surface of cancer cells. The first monoclonal antibody for treating cancer was approved in 1997, for treating non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Since then, more than a dozen monoclonal antibodies have been approved to fight breast, head and neck, lung, liver, bladder and melanoma skin cancers. Monoclonal antibody therapy has extended some patients’ survival by as much as 10 years.

Dr Parameswaran Hari, haematologist, Medical College of Wisconsin, says that the development of orally active small molecules called tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) starting with Imatinib for a type of leukaemia called chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) has reinforced cancer armamentaria. TKIs block enzymes called tyrosine kinases. These enzymes are responsible for sending growth signals in cells, so blocking them stops the growth and division of cells. “Now, there are a variety of enzyme inhibitors that are applicable in many cancers such as Sunitinib, Sorafenib, Dasatinib, Lapatinib and Miostaurin,” says Hari.

However, he opines that the use of combination chemotherapies with or without radiation to cure childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia, Hodgkin’s disease and testicular cancer was the step that changed the overall treatment scenario.

Innovations in cancer treatment aim to address a set of issues faced by health care providers and patients. These include aggressive treatment accompanied by unwanted side effects, tumour recurrence after treatment, surgery, or both, and aggressive cancers that are resilient to widely utilised treatments. Many scientists believe the discover of immunotherapy drugs to be a penicillin moment in the quest for cancer cure. The war on cancer is not over, since a full and total cure is still a work in progress.

Menon is scientific media editor at Trial/Applied Informatics Inc. She manages and hosts CureTalks, an international online radio talk show on cancer research and health care.