As an unusually eventful year draws to a close, a development offers quiet reassurance about the health of our parliamentary processes. Amid frequent commentary on legislative disruption and partisan gridlock, I had the privilege of participating in a rare bipartisan exercise that has, thankfully, defied the prevailing circumstances.

Last week, the Select Committee on the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) unanimously submitted its report to the Lok Sabha after completing its scrutiny of the government’s proposed overhaul of the 2016 law. There was recognition that the IBC has helped turn around banks’ non-performing assets (NPAs) with recoveries in recent years of Rs50,000-Rs60,000 crore per annum. There was also broad consensus that a major reboot is required to tighten resolution timelines and incorporate several important suggestions from stakeholders.

I had the honour of chairing this cross-party committee, and what made the exercise particularly satisfying was the spirit in which MPs, from both the governing and opposition parties, worked—in a cordial, cooperative and professional atmosphere. Crucially, this work unfolded away from the glare of cameras.

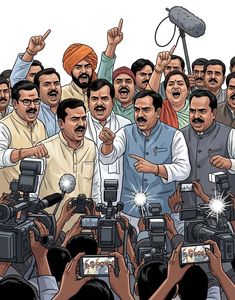

That absence is not incidental. While the proceedings of both houses of Parliament are broadcast live, boosting transparency, parliamentary committees remain outside this ambit. Decades ago, then speaker Somnath Chatterjee resisted calls to allow live coverage of committee hearings. His judgment, with the benefit of hindsight, appears prescient. Cameras, while valuable for public accountability, can also distort systemic incentives.

For elected representatives, the presence of cameras often triggers a performative instinct—the temptation to speak over colleagues, and, instead, address an external audience. In Parliament, this has often translated into grandstanding and disruption by the opposition, even when it compromises their ability to exert pressure on the government through questions, debates, amendments and other procedural tools. Committees, insulated from this dynamic, have therefore retained their character as spaces for genuine deliberation.

What TV cameras did to legislators, social media has now done to society at large. Social media platforms, through algorithm-driven amplification, increasingly shape how citizens encounter information. By flooding users with content aligned to their initial clicks, these platforms create echo chambers that crowd out alternative viewpoints and narrow discourse—conditions hardly conducive for reasoned discussions or inferences.

This amplification of selective perspectives runs counter to rational inquiry. Human progress has rested on questioning assumptions, weighing evidence and engaging with competing ideas. When debate gives way to emotional reinforcement, whether through political theatre or algorithmic feeds, the quality of collective decision-making suffers severely.

Against this backdrop, the work of the IBC Select Committee offers a modest but meaningful counter-example. It demonstrates what can be achieved when systemic incentives favour cooperation over confrontation, and when policy is examined through a pragmatic, problem-solving lens rather than partisan reflex.

The existing IBC has helped make India’s banking sector stand on a far firmer footing, even by international standards. This major reboot will further dramatically improve the situation. There are many parliamentary committees that have had similar outcomes. That is reason enough for optimists to hope for—and contribute to—a more effective democracy.

Baijayant ‘Jay’ Panda is National Vice President of the BJP and is an MP in the Lok Sabha.