There is an open door, shut by a closed mind….” This is the line that grabbed me when I opened Asha Thadani’s catalogue, Broken—Dalit Lives, which introduced viewers to her just concluded exhibition of photographs in Delhi. Asha has been chronicling the lives of the most marginalised citizens of India, and reminding us powerfully that, “The human spirit is never in chains, imagination is never in shackles and creative expression through art, song, verse and dance, allows them freedom of the mind, in a defiance of the caste cabal.’’ Asha’s searing series of photographs, visualises the lives of 10 such dalit communities, in the fervent hope that at least a single door for a closed mind opens.

Asha is a photographic artist based in Bengaluru, and has been creating images that explore power structures since 1996. Her works have received international recognition and been shown at important museums like the Albert-Kahn Museum and Garden, Paris, and the National Centre for the Performing Arts, Mumbai. Nominated for the prestigious Henri Cartier Bresson Award (2015), Asha continues to address social injustices by deep diving into the human tragedy behind the most dehumanised segments of our society. She writes, “The dalit life has been one of isolation and pain, and systemic injustice.’’

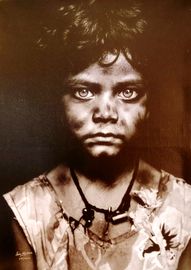

As I went through the wonderfully written text by popular podcaster, writer and magazine publisher, Ramjee Chandran, my eyes refused to focus! Let me explain. There was one particular image of a little girl, at the coal mines of Jharia, that shook me up. I simply couldn’t look the child in the eye without cringing in shame. I started to read the bone-chilling text accompanying this section, titled The Unseen Suffering, and my stomach churned—rogue mines employ four lakh people, including women, and children who are not yet 10. They live as bonded labour and work 18 hours a day. That little girl’s direct gaze—defiant, scorching, challenging—began to haunt me. And I reached out to Asha, through our common friend, the extraordinary Prasad Bidapa, to express what I felt about Asha’s powerful work. That little girl now resides in my home in the form of a life-size photograph, sent by Asha. It’s interesting to note that her presence has disturbed the domestic equilibrium enough for visitors who stop and stare and sometimes ask, “But why would you want such a picture on your wall? Doesn’t it bother you?” Of course, it does! Which is why it is there.

There is another, equally compelling portrait of a handsome, rugged young man posing with a cluster of goat heads. Yes, goat heads. I plead ignorance! I had no idea that a dalit tribe called the Holeyas harvest the brains of goat carcasses for a living; the brain being the part of a goat that fetches the most money. Dalit males who specialise in extricating the brain are as young as 10 or 12. Their life expectancy is 35 to 45. They often die of bites from the ticks on the heads of the goats being burned, or from toxic furnace fumes. The young man stares back, his eyes blazing—pride? Anger? Rebellion?

Some days ago Prime Minister Narendra Modi consecrated the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya with much pomp and ceremony. More than a century ago, in a village in Chhattisgarh, Parsuram Bharadwaj, a dalit, was stopped from entering a temple. He decided to express his protest by tattooing the word Ram on every part of his body, as a challenge to Hindu orthodoxy. Others followed. Today’s Ramnamis, looking for jobs in big cities, don’t wear their devotion to Ram as visibly. Asha calls the Ram tattoos, “A chant in writing.” It is the devotion of the defiant. I cannot wait to meet Asha—she has given so much ásha (hope) to India’s most wretched.