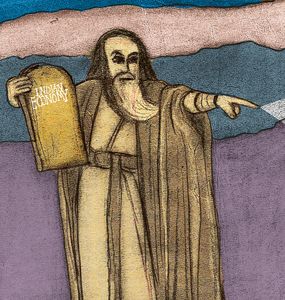

There are many definitions of what has been dubbed the Moses syndrome. My favourite one goes like this—“A delusion characterised by the belief that one has been chosen by God, destiny, or history to lead others to the Promised Land.” Some of the policy pronouncements of the ‘recently imported economists’—Raghuram Rajan, Arvind Subramanian and now Viral Acharya—read like that. “We have seen the light. Here are our Ten Commandments. Obey them or else the markets will be on fire, the rupee will tumble, growth will slip, debt and deficit will rise, and such like.”

Acharya, deputy governor of the Reserve Bank of India, may have valid concerns, but there is what may be called ‘Central bank dharma’—a manner of articulating one’s concerns that is fundamentally different from the rhetoric of a smart academic. For a senior Central bank functionary to begin his speech on economic policy and institutional autonomy in India with a story from Argentina, an economy in crisis, was bizarre. What was he smoking?

Many have already commented on the content of Acharya’s speech. One important consequence of his sharply worded speech could be that he is taken less seriously than he ought to be. The Indian state does not like excessive hype in the manner in which policy makers convey their opinion. I am surprised that RBI Governor Urjit Patel approved of the text. Patel has been around for a long time and would have closely observed the manner in which many of his distinguished predecessors articulated the idea of Central bank autonomy without deploying alarmist language.

There is a larger issue raised by the recent behaviour of the very bright, imported economists. There is no question that each one of them is very talented, with an enviable international reputation. But then, so were some of the grand old economists of the past. Manmohan Singh was an award-winning economist with terrific recommendations from his professors at Oxford and Cambridge. So were many other ‘imported economists’ of his generation. That earlier generation was as comfortable in the corridors of power as in lecture rooms. However, returning home they defined their audience as the political and policy leadership of India. Hence, they articulated their views in such a manner that policy makers understood them and respected them, rather than feel slighted by them.

There is now a clear danger that a chastened bureaucracy, repeatedly admonished by bright young professionals with an eye to their western peers, may think twice before inducting more imported talent at higher levels of government. A pity because India needs to draw on the vast pool of talent available within the global Indian diaspora.

The Indian system also has to learn to deal with the idiosyncrasies of a generation that has grown up being told that they were top of the class. The Moses syndrome is a common affliction of those who have climbed the professional ladder through their individual excellence. There is in them, therefore, a tendency to lecture those who have not yet seen the light of God.

Non-resident Indian professionals based in the United States are particularly prone to the Moses syndrome. It would be a pity if recent experience with imported economists created a bias against imported talent in general. However, those being hired for senior positions in government should be helped to get acclimatised to the Indian way of articulating opinion from positions of power. The Indian system places a premium on maturity and subtlety in policy articulation. It abhors hubris and intellectual arrogance.

Baru is an economist and a writer. He was adviser to former prime minister Manmohan Singh.