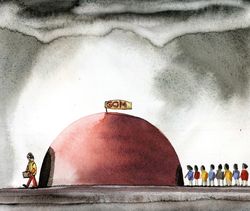

The phrase ‘group of ministers’ is anathema to the Narendra Modi government, as it was a much ridiculed tool of decision-making in the Manmohan Singh government. In the decade-long rule of the Congress-led United Progressive Alliance, the GoMs were constituted on every third important subject before the cabinet. Pranab Mukherjee, till he became president, headed the most number of GoMs; fellow ministers frequented his offices in different ministries.

When Modi did constitute these groups—for inter-ministerial issues that needed to be sorted out—they were given complicated names to avoid the acronym GoM. One popular title was ‘alternative mechanism’, but the names kept changing. A ministerial group headed by Home Minister Amit Shah to decide on disinvestment is called Air India-Specific Alternative Mechanism. But its recommendations need to go to either the cabinet or the cabinet committee on economic affairs, as it happened during the UPA government.

But, when the Covid-19 outbreak and the subsequent lockdown called for large-scale coordination among ministries, a group of ministers was constituted under the chairmanship of Defence Minister Rajnath Singh. The group met regularly in the initial weeks of the lockdown to solve complex issues.

But the frequency of the meetings came down as there were fewer issues to consider as the lockdown progressed, and also because another governmental mechanism took over. Instead of burdening ministers with routine subjects, the cabinet secretariat and the Prime Minister’s Office set up 10 committees of secretaries of ministries. These committees were tasked with specific issues like ensuring availability of drugs, protective gear and other medical equipment, transportation of goods and people, protection of migrant labourers, supply of food grains and other essential commodities, community messaging and propping up industries. Members included heads of large public-sector companies like the Food Corporation of India, Indian Oil Corporation, National Housing Bank, Employees Provident Fund, Indian Railways and National Highways Authority of India and various port trusts.

The secretaries would coordinate among themselves and consult with ministers only on policy issues. Officials deputed from the Prime Minister’s Office would give the final green light after consulting with P.K. Mishra, principal secretary to the prime minister. So there was a sense of quicker decision-making.

These committees also created the framework for the Rs20 lakh crore economic stimulus package and the slew of reforms announced by Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman. Some ministers wanted to announce measures relating to their sectors, but they were advised that it would be better if a single minister announced the whole package. Fellow ministers could take ownership by organising a big event to implement the decisions involving their ministries. Thus, Coal Minister Pralhad Joshi could organise a big virtual function to launch the privatisation of coal mining, which was attended by Prime Minister Modi.

The slew of reforms put a heavy load on the legislative affairs department of the law ministry, which had to quickly vet the drafts of ordinances issued by President Ram Nath Kovind and several new rules which were gazetted. It is to be seen how this new system to tackle the fallout from health and economic emergencies would redefine the minister-bureaucrat relationship in a government dominated by Modi’s power and persona.

sachi@theweek.in