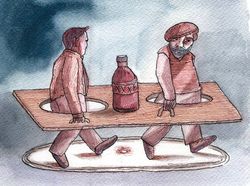

People get “high” after consuming good quantities of alcohol, but ministers and the top bureaucrat of Punjab are in high temper over a discussion on liquor policy. Finance Minister Manpreet Singh Badal, who has led the ministerial revolt against Chief Secretary Karan Avtar Singh, however calls it a “high” policy debate, not an ego clash.

But the row over liquor licenses between ministers and Avtar Singh—who was heading the excise department—has given light entertainment in a state hit by lockdown. Chief Minister Amarinder Singh gently chided Badal and his colleagues for walking out of a liquor policy meeting. During the meeting, Avtar Singh felt that ministers were supporting liquor sellers, while the ministers accused the bureaucrat of owning a distillery through his son. The chief minister felt that the ministers should have asked the chief secretary to leave the room, as he is below the ministers in protocol.

The ministers said they would boycott the cabinet meeting if Avtar Singh is present. Amarinder Singh asked his favourite bureaucrat to take leave for half day when the cabinet was meeting. When the ministers attended but protested the behaviour of Avtar Singh, the leader asked them to dictate an “unofficial” resolution of their intention to boycott. But he also asked them to pass an “official” resolution that the chief minister alone will decide on liquor policy. Within an hour, Avtar Singh was back at the side of the chief minister. However to keep peace in cabinet, Avtar was divested of excise and taxation departments a day later.

In several states, bureaucrats close to chief ministers have caused resentment among ministers. In Odisha and Bihar, chief ministers Nitish Kumar and Naveen Patnaik have favoured such “super bureaucrats” with Rajya Sabha memberships. In Haryana, Home and Health Minister Anil Vij—who has had differences with chief minister Manohar Lal Khattar—finds himself being overruled by the chief secretary on orders from above.

Under the government business transaction rules, if there is an irreconcilable difference on a subject between a minister and a departmental secretary, then the subject should go to the cabinet. At the Centre, the cabinet secretary is never the secretary-in-charge of a ministry and does not report to a minister. But in states, the chief secretary sometimes handles a department, and can have more than one boss. That is what has happened to Avtar Singh.

But there have been clashes in the Union cabinet, too. Deputy prime minister Devi Lal used to complain that prime minister V.P. Singh was using the cabinet secretary and other officials to thwart proposals from the agriculture ministry.

In 1994, there was a fierce exchange of words between the Union minister of state for food, Kalpnath Rai, and cabinet secretary Zafar Saifullah. The abnormal rise in sugar prices had become a crisis for the P. V. Narasimha Rao government. The civil supplies ministry proposed procurement of sugar at lower prices, which Rai opposed. Saifullah argued against Rai. The high-tempered Rai stormed out of the cabinet saying Saifullah and other officials were chaprasis (peons). The top bureaucrats were incensed and started a signature campaign.

Rao appointed a retired bureaucrat to hold an inquiry; when the uproar died down, he dropped Rai from the government. By then Saifullah, too, retired. In subsequent governments, food and civil supplies have been brought under one minister to avoid policy clashes supporting the producer and the consumer. Amarinder Singh would find his own solution to the “high” dispute at the pinnacle of the Punjab government.

sachi@theweek.in