Will Emmanuel Macron’s second term as French president mean more of the same? To everyone’s relief, he himself has assured “it won’t be the continuity of the previous five years, but it’ll be a new method to try to ensure better years”. It is unclear what this “new method” is.

During his first term, Macron’s neoliberalism spurred growth, employment and enabled France to economically outperform other European countries. Tough Covid-19 lockdowns were sweetened with aid packages. His vigorous backing strengthened the European Union. But domestically, he was labelled the elitist, arrogant “rich man’s president”.

Data supports street resentment: the rich have become richer and the poor poorer. Macron’s fuel tax unleashed the gilets jaunes, the “yellow vest” agitation that fomented and cemented widespread anger against him. His contentious pension reforms floundered as they provoked strikes and street protests, the biggest since the 1968 upheaval. Nobody wants more of this.

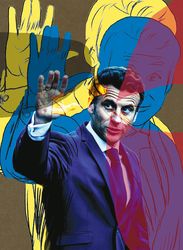

Now Macron promises to be “everyone’s” president. Prima facie, his 17 per cent lead over his rival, the far-right leader Marine Le Pen, in the runoff, appears impressive. But in France, nothing is what it seems. The French have a penchant for complexity, nuances, layers, argument and paradoxes. As they say “en même temps”—“at the same time”.

Macron won, but at the same time, he got two million votes less than in 2017. The far right lost, but at the same time, they won an unprecedented 42 per cent of votes. The two major right-wing parties together polled more than Macron did. Only a third of the electorate voted for him—the lowest for a winning president since 1969.

Macron was the first president in 20 years to win re-election. At the same time, 28 per cent of voters abstained, the highest in over 50 years. Two-thirds of the electorate that Macron must woo embody apathy or antipathy. Macron admitted, “Our country is full of doubts and full of divisions.” Touché.

Macron passed the re-election test. But a looming test can make or break his presidency—the June parliamentary elections. Macron swept the parliamentary elections in 2017. Since then, his party, La République En Marche, has lost all local elections. French society is deeply polarised. The traditional centre-left and centre-right parties that ruled France until Macron stormed the Élysée Palace in 2017 are fading into irrelevance.

The electorate is now fractured into three hostile blocs: centrist Macron, far-right Le Pen and far-left Jean-Luc Mélenchon. All three vie to get majority in the parliamentary polls and bag the prime ministership. If Mélenchon succeeds, he will overturn Macron’s welfare cuts and hire-and-fire labour policies. Le Pen will leash Macron’s pro-immigration and EU polices. The quarrelsome troika could create legislative gridlocks that could impact French and even EU lawmaking. But for now, EU leaders are hugely relieved that the nationalist, anti-EU, anti-NATO Le Pen lost the presidency.

Macron loves engaging with lofty matters. But now he wrestles with bread-and-butter issues: crime, health care, education and inflation that has hiked food, fare, fuel bills up to 29 per cent. He must focus on difficult domestic issues though he prefers to be a European gladiator and a global statesman. But the success of his foreign interventions during his first term, from Russia to Mali, Lebanon to Libya, range from minimal to dismal. Macron promises that Macron II will not be a repeat of Macron I, predicting his second and final term “will not necessarily be tranquil, but will be historical”. Certainly it won’t be tranquil. At the same time, not necessarily historical.

Pratap is an author and journalist.