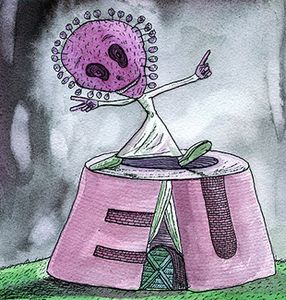

We have witnessed the coronavirus’s capacity to ravage lives and livelihood. Experts wonder if it can ravage and unravel the European Union, the world’s biggest and mightiest bloc. The person thinking this unthinkable thought is none other than French President Emmanuel Macron, EU’s doughtiest defender. In a Financial Times interview, he warns that the EU “as a political project will collapse” if the EU’s richer northern countries fail to bail out the pandemic-stricken southern members of Italy and Spain.

When Covid-19 erupted, instead of showing solidarity, EU countries distanced themselves from each other, closed borders and struggled to control the pandemic in their own countries. Italy did not even get masks from the EU, making anti-EU sentiments as lethally contagious as the virus. A poll revealed 88 per cent of Italians feel the EU failed them, prompting European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen to publicly apologise for “not offering a helping hand”. With an eye on his own nation’s right-wingers, Macron predicts the virus will fuel populist anger against the EU in Italy and Spain, unless the bloc shows solidarity.

But solidarity is just another word for money. Rich, financially disciplined northern countries like Germany and the Netherlands support giving emergency relief to the southern states—€100 billion to protect jobs. But they say the pandemic cannot be an excuse to waive loan repayments. Long before Covid-19 struck, Italy’s debt was unsustainable. Observes Italian investment banker Alessandro Ciravegna, “The Italian economy has underperformed on almost every metric for decades, due in large part to structural inefficiencies that Italians acknowledge but simply refuse to address.” For example, about 60 million tourists travel to Italy every year and Italy has a large global diaspora. Yet Alitalia has never been solvent. A thriving black economy means low tax revenues. Adds Ciravegna, “Foreigners who have ever had to deal with any part of the judicial system run and never return.”

The protestant northerners are seen as frugal, hardworking and law-abiding. The southerners, lazy and wasteful. Former Dutch Finance Minister Jeroen Dijsselbloem famously told southern Europeans, “I attribute exceptional importance to solidarity. But you also have obligations. You cannot spend all the money on drinks and women and then ask for help.” Southerners say the “conditionalities” attached to the funding are unacceptable, while northerners retort that even when parents pay for children’s education, it is on the condition that they attend classes and study hard. Pleads Ana Botin, executive chairman of the Spanish Santander Bank, “We are in this together. Countries with the broadest shoulders should carry more of the burden.”

Stoking the north-south stereotypes, Italy’s nationalist leader Mateo Salvini warned that if Germans do not give money, Italians would not buy BMWs. Germans blew a fuse at the notion that they must work full shifts in their factories, pay taxes and then donate their tax revenue so that Italians can cruise in BMWs. They asked where Italian solidarity was when German workers sacrificed pay hikes to make their economy healthy again.

This infectious virus, like a secret agent, enters through chinks in the armour. It cannot create cracks in the EU, but it can certainly widen existing ones, especially when the bloc lacks the immunity of social cohesion. Even today, there is no European national hero or monument that member states can agree on to adorn the Euro banknotes. Currently, they feature non-existent classical buildings. Two-thirds of Italians now feel EU membership is a hindrance. “This crisis is the EU’s biggest test yet,” warns Botin. One of EU’s founding fathers, Jean Monnet had said, “Europe will be forged in crisis.” It can also fall apart.