As always, my phone went off at 7am with the consults for the day. I did a double take when I saw one of the names. It was a colleague and friend. 'No way', I thought to myself. Mike was a triathlete and someone I looked up to. I would marvel at his updates on Facebook as he trained for the Ironman Triathlon, which consisted a 2.4-mile swim, a 112-mile bicycle ride and a 26.2-mile run. I watched incredulously (on Facebook again) as he crossed the line 14 hours later and put him on my wall of fame. This was two months ago.

Now Mike wasn’t your typical triathlete, which made his feat all the more incredible. He was slightly on the heavier side, and he was battling a host of musculoskeletal issues. I looked at his EKG and labs, and knew what I was going to do even before I walked into his room. The EKG showed subtle indications that his heart was not getting enough blood and the tiny bump in his cardiac enzymes confirmed this. I walked into the room, and broke into a smile seeing him in the hospital gown. We shook hands, and he told me about the ache in his jaw and chest. We both knew that this was angina, the clinical manifestation of his heart protesting the lack of blood flow. What neither of us could understand was how he got through the Ironman just two months ago. Off we went to cardiac catheterisation lab.

How do you do a procedure on a friend, colleague and mentor without bias? I break it down into stages, like I always do, which helps me concentrate on the task at hand. I got the catheter into his coronary arteries and, as I took the pictures, I was amazed that he was still alive. All three arteries were significantly blocked. I wouldn’t have expected him to run a mile without dropping dead, forget do an Ironman. He needed bypass surgery; stents would be a band-aid. He took the news well, and his question to me was, 'Will I be able to compete in another Ironman?'

The science behind triathletes and cardiac events is evolving. An analysis published in the Annals of Internal Medicine last year looked into three decades of USA Triathlon events involving five million participants. The results showed a surprisingly high rate of 1.74 cardiac deaths or cardiac arrests per 1,00,000 participants. Now this may not seem like a high number, but is four times higher than in other healthy athletes. Interestingly, men account for 85 per cent of the events, the average age being 46. There is a significant rise in events in those above 60—an astonishing 18.6 events per 1,00,000 participants. So, if you are a male above 60, you better have a chat with your friendly cardiologist.

A deeper dive into the data shows that two-thirds of the events occurred in the swimming portion. The duration of the swim did not matter. In fact, the duration of the triathlon did not matter either, with half the deaths occurring in short-distance triathlons. Autopsy data shows that half the patients with events had existing coronary artery blockages.

How do we make sense of all this data? The cardiology community has long suspected that too much exercise can cause inflammation and lead to scarring of the heart. How much exercise is too much is of course the million-dollar question. My guess is that like most things in medicine, there is no magic number. It is different for different people, with genetics, age, preexisting heart issues and existing risk factors all playing a significant role.

The swimming portion is particularly interesting. If you have ever been in a triathlon, you know this portion can get nasty, with people swimming over you, pushing you under, not to mention kicking you in the face when you come up to breathe. The combination of a high heart rate, decreased oxygenation when pushed under, and underlying heart disease can potentially cause your heart to fibrillate—a terminal event without medical help. By the time someone spots you, drags you to shore and gets a defibrillator on you, it is probably too late.

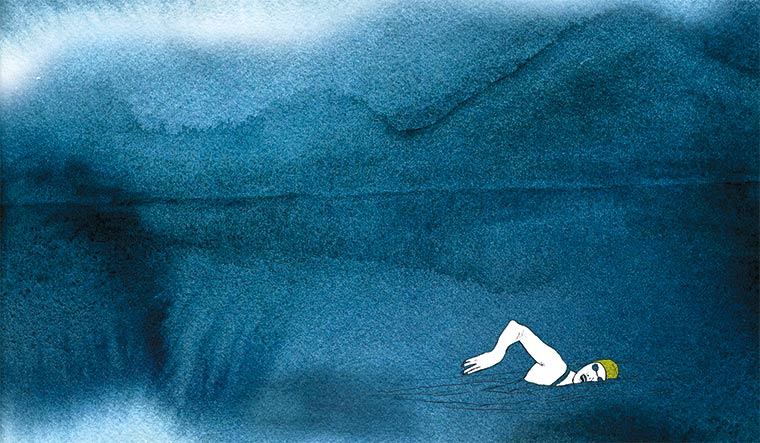

Four months later, I was looking at the ocean one Saturday morning, contemplating my swim. I had joined the local triathlon group two months ago, and was getting used to bringing up the rear. As the crew rolled in and the social event prior to the swim started, I saw a familiar figure—it was Mike. ‘Welcome back,’ I said. We grinned at each other and he gave me a hug and thanked me again.

The ocean was calm that morning; I watched the sun rise over the ocean as I kept turning to breathe on my left. It was a glorious sight, one that keeps me coming back. Mike came in last, a place usually reserved for me. I wasn’t called ‘shark bait’ for nothing. I waited for him at the shore and we shook hands as he came in. As we walked across the beach in silence, I glanced at him. The sun was on his face and he was smiling.