When P.V. Sindhu won an Olympic silver five years ago in Rio de Janeiro, all she wanted as a gift from her parents was a puppy. They bought her a labrador, and she named it, quite aptly, Rio.

As the puppy grew, so did India’s expectations of Sindhu. She struck silver at the 2018 Commonwealth and Asian Games, and became world champion, a title she desperately wanted, in Basel, Switzerland, in 2019.

Now 25, India’s gold medal hopeful is wiser and more experienced. As she prepares for a second crack at an Olympic gold in July, Sindhu is training harder than ever. She wakes up at dawn, trains with Korean coach Park Tae Sang in Gachibowli, Hyderabad, and then does fitness training at the Suchitra Academy there. Lunch is at home, with some much-needed rest. Evening is for more training, followed by family time and playtime with Rio, before going to bed.

Early this year, in a major move, Sindhu moved out of the Pullela Gopichand Academy; she now trains at the nearby Gachibowli indoor stadium, away from the core group of shuttlers she grew up with. It has a large competition hall, similar to the one she will play in in Tokyo, and it would be easier to simulate those conditions.

Also, she no longer trains with chief coach Gopichand. The former All-England Open champion had laid the foundation of her game.

Though Park and Gopichand work in tandem, the familiar sight of the latter sitting near the court during Sindhu’s matches is a thing of the past. Park travels with Sindhu for competitions, accompanied by a physiotherapist and trainer under the Target Olympic Podium Scheme (TOPS).

Post-lockdown, Sindhu’s return to competitive badminton has been slow yet steady. The Badminton World Federation resumed the World Tour with the Thailand leg in January. Sindhu lost in the first round of the Yonex Thailand Open—her first tournament after a year—but reached the quarterfinals in the Toyota Thailand Open.

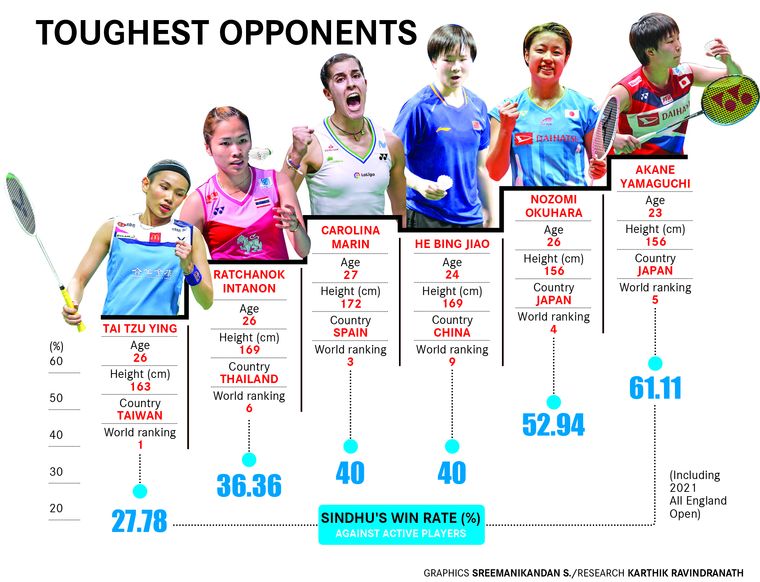

In the European leg a month later, she reached the final of the Swiss Open, but lost to world number one Carolina Marin. The All England Open followed, albeit with a depleted field. Sindhu beat Japan’s Akane Yamaguchi in a thrilling quarterfinal, but lost to 11th ranked Pornpawee Chochuwong the next day.

Former chief national coach U. Vimal Kumar, however, said there were no concerns about her form. “I was quite impressed with the way she played Yamaguchi,” he told THE WEEK. “It was her first good match after a long time. Sindhu is our best bet for an Olympic medal at Tokyo. All she needs is a couple of matches more and to work on some specific areas.”

He also stressed the importance of Sindhu being in a good place mentally. “Badminton is an individual sport,” he said, “and you have to be happy in an environment. For her, mental peace is very important.”

He added that she and Park were working well together. “Maybe she could get a few better people to spar with,” he said. “[She] needs a few more matches like the one against Yamaguchi.”

Sindhu’s recovery from the Yamaguchi match, however, was a concern. “She is not unfit, all she needs is a very specific recovery plan,” said Kumar. “More than the coach, it is her physio who should be aware of that.”

He also felt that maybe Sindhu faltered in her strategy against Marin. “She tried to push the pace, [there was] too much focus on attacking Carolina,” he said. “Instead, she should have kept the shuttle in play. But I am not worried. Sadly, expectations are such that [people] want her to win all the time.”

But Sindhu soldiers on. Always friendly and polite, Sindhu remains, as former doubles player and fellow Hyderabadi Jwala Gutta said, “a sweet girl”. “Obviously, she has grown up a lot since she started, but I like that she is still grounded,” said Gutta.

The pride in P.V. Ramana’s voice was obvious as he talked about his daughter. “She is so sensitive and committed,” said the former volleyball player and Arjuna awardee. “She has never said no for any session. I know I have troubled her a lot, at times even on Sundays. If I tell her ‘Do this beta, why can’t we try this?’, she will do it.

“Earlier (pre-Rio), she was more emotional,” he added. “She has slowly become more aggressive on court and now, especially, I see that she is a bit more determined. Mentally, too, she is stronger.”

Said Gutta: “She knows there is a lot more responsibility on her shoulders, but she takes that pressure well. Her game is much stronger [now]. All she needs is loyal people who really want her to win.”

With Sindhu having played so many international tournaments, Gutta said she did not need much on-court guidance. It is off court that Sindhu’s badminton life has been making headlines.

Late last year, in the midst of a lockdown in Europe, Sindhu went to London to train at the Gatorade Sports Science Institute. The news became public only when she posted a picture of her with sports nutritionist Rebecca Randell.

“She asked us but we told her it was not the right time as there was a pandemic,” said Ramana. “We said she could go when she was free. [She said] ‘Daddy, when will I be free?’ So we told her it was up to her; she has grown up now!”

While both Sindhu and her father refuted reports of differences within the family over this decision, he did reportedly make some damning allegations against Gopichand, saying that the coach had not taken interest in her training after the 2018 Asian Games. He also said that she was not given a proper practice partner. While Ramana has at times gone public with his dissatisfaction with the coach’s methods, Gopichand has maintained a studied silence. Sindhu has had to step in more than once to defuse the situation.

Ramana has been a helicopter parent, standing at Sindhu’s side throughout her life. He could not go with her for the first two events post-lockdown as the family was in the process of moving to a new house. However, he had asked the physiotherapist/trainer to send him videos of her training sessions.

About the England stint, he said: “We are happy it was refreshing. Now she will not ask us to go and train there again.”

Ramana is satisfied with her training individually with Park and a separate set of support staff; Gopichand, meanwhile, has further delegated training of senior team members to the rest of the foreign coaches.

Ramana was confident that training without Gopichand “will not affect her at all”. “If you train her, she will give you her 100 per cent,” he said. “The quality of an athlete bringing laurels to the country is purely based on the commitment, hard work and desire of the player.” In fact, he said that if Gopichand could produce a Saina Nehwal or a Sindhu, he could produce more champions.

Gopichand, it seems, has made peace with the fact that Sindhu is no longer under his direct watch. However, he is still very much in the loop and he and Park take decisions on Sindhu’s game. He knows Sindhu is India’s best bet for an Olympic medal and, reportedly, does not want to say or do anything that might affect her preparation. For the time being, the distance between Sindhu and Gopichand has lowered any animosity between Ramana and the coach.

Ramana acknowledged the increased pressure of expectations on Sindhu, but said that he and his wife have been trying to ensure that it does not get to her. “We tell her, ‘You have got everything... now whatever you are getting is bonus, beta,” he said. “Play with all your heart and enjoy the game.’ That is all we tell her.”