‘FLY IN, FLY OUT’ was the only way foreign lawyers were permitted to function in India. Fly in, advise your client and fly out. There had been stiff resistance to the idea of foreign lawyers and firms setting up practice in India, and whether to open up the Indian legal system and in what manner had been one of the longest pending and most intensely debated issues. In this backdrop, the notification issued by the Bar Council of India (BCI), the regulatory authority for legal services in the country, on March 13 allowing foreign lawyers and firms to set up practice in the country, although with riders attached, came as a huge surprise for the country’s legal fraternity.

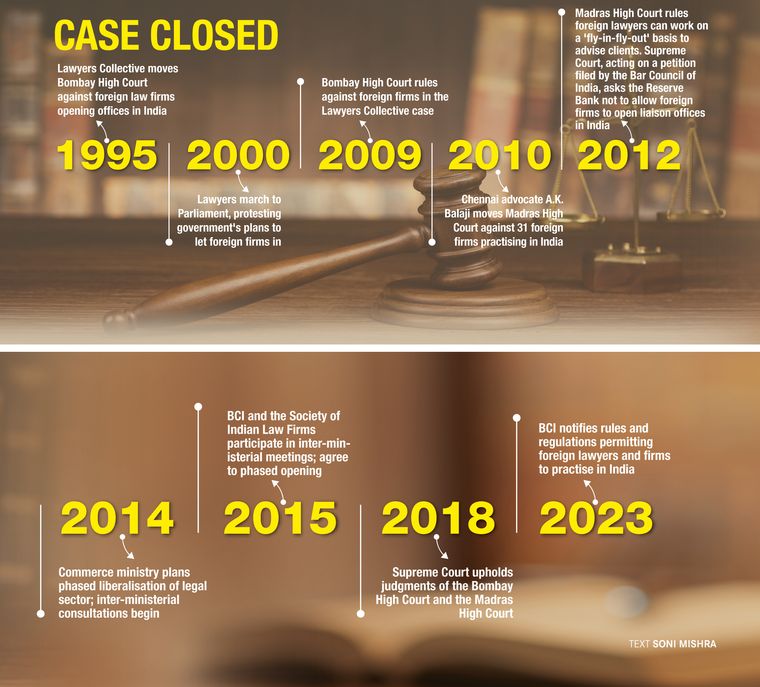

Post liberalisation of the Indian economy in the 1990s and especially since the BJP-led NDA government came to power at the Centre in 2014, the discussion on opening up the legal sector in the country had gained an element of urgency. It was discussed threadbare by policy makers, the Law Commission of India, the BCI and the representative bodies of lawyers. The discussions among policy makers took place even as the courts, including the Supreme Court, had their say in the matter. The BCI notification has only intensified the discussion. If there is guarded optimism among foreign players, the Indian legal fraternity is divided on the pros and cons of the move.

Foreign firms had been looking to tap into the growing Indian legal market, following an increasing number of foreign companies investing in the country post liberalisation. These companies had thus far been looking to international arbitration centres such as in Singapore, Dubai or London to meet their legal requirements. Many foreign firms had already set up India desks overseas to cater to clients operating in India and looking for legal services in another jurisdiction.

As per the Bar Council of India Rules for Registration and Regulation of Foreign Lawyers and Foreign Law Firms in India, 2022, foreign lawyers can practise foreign law and diverse international law and arbitration matters in India on the principle of reciprocity. They cannot practise Indian law and their functioning would be limited to non-litigious matters. They can be allowed to practise transactional work or corporate work such as joint ventures, mergers and acquisitions, intellectual property matters, drafting of contracts and other related matters on a reciprocal basis. However, they cannot be involved in any work pertaining to conveyance of property, title investigation or similar works. Foreign lawyers or firms would have to be registered with the BCI, which would be valid for five years.

Many prominent foreign law firms such as Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan LLP; Clifford Chance; Ashurst; Allen & Overy; and Baker McKenzie are looking keenly at India as a legal market with great potential. Most of them already had services focusing on India but provided elsewhere, where their firms and lawyers could provide clients with legal services beyond the shackles of the ‘fly in, fly out’ restriction.

According to an official in a foreign law firm who spoke on condition of anonymity, international firms will be cautious in making their moves in the Indian market. First and foremost, they would want greater clarity on the terms and conditions on which they can function in India. There is also a desire for the issue to settle down a bit before they explore their opportunities here. Also, setting up office in India would be a gradual process and at present it would be difficult for them to spell out for certain when and how they will begin their India operations within Indian boundaries.

“We are reviewing the Bar Council of India’s announcement carefully,” said Allen & Overy. “It is early days and we will continue assessing the details and evaluating the options for our clients and our market-leading India practice.”

However, Piyush Prasad, counsel (foreign law) at WongPartnership LLP, Singapore, said that while the full scope of the regulations is not known yet and certain aspects may require clarification, “certain firms will be willing to take the first mover advantage to be on the ground in India for their clients, whilst others will watch the space with anticipation before entering the market”.

Indian firms, on the other hand, are divided on the pros and cons of the move. Many feel it is a step that was belated and the country has lost out on precious time to emerge as a force to reckon with in international arbitration and that the opening up of the legal sector will have a wide-ranging positive impact on the legal industry in the country. It is felt that the move would bring in greater professionalism and accountability, and enhance the image of the Indian legal sector globally.

“This is a watershed moment for the Indian legal industry. It is a welcome move that would result in more structured, professional and mature legal practices,” said Sameer Jain, managing partner, PSL Advocates & Solicitors.

As India attracts growing foreign direct investment, international corporates have been looking at other arbitration centres to sort legal issues so that they can seek the advice of their chosen firm. Singapore, in particular, has been a major beneficiary. International firms have also taken on board Indian lawyers to help with India-specific services.

Many Indian lawyers feel that while this was a highly contentious and intensely debated issue, it will help that a decision has finally been taken and there is clarity in the matter. According to Rohit Jain, managing partner, Singhania and Co., a big positive will be the greater opportunities for Indian lawyers. “Foreign law firms will have to take on board Indian lawyers, because their role is limited to foreign law and Indian lawyers will be needed to provide advice on Indian laws,” said Jain.

According to Prasad, when he was practising in India, his collaborations with foreign counsel had been an extremely enriching experience. “My hope is that a closer interaction with foreign lawyers will provide a platform for Indian lawyers to learn from the experiences of their counterparts and vice-versa,” he said. “As regards competition, it keeps the market participants on their toes and ultimately benefits the end user.”

There is a feeling that retainership for lawyers in the country will go up since the options for them increase manifold. This is coupled with the concern among mid-sized and small-sized firms of poaching of their talented lawyers.

Indian law firms, initially wary of the entry of foreign firms, had over time lowered their guard, convinced that the firms in the country could compete with foreign players. But they still wanted the government to open up the sector in a phased and sequential manner. It is pointed out that international players, especially the UK and the US, have lobbied hard for opening up of the legal sector. It is felt that the sense of urgency in the BCI announcement has come from the UK-India Foreign Trade Agreement negotiations.

Senior advocate Lalit Bhasin, president of Society of Indian Law Firms (SILF)―a group of 125 law firms―said the notification went against the Advocates Act, 1961, and the Supreme Court’s order of 2018 that stated that foreign lawyers and law firms cannot practise in India, litigation or otherwise. He also voiced concerns about there being an uneven playing field for Indian firms and lack of clarity on how reciprocity would be ascertained and ensured.

“Yes, it is bad in law,” said Bhasin. “These regulations have come out of the blue. We had a meeting in early March, convened by the commerce secretary. I was invited to attend as president of SILF. The Bar Council of India was invited, but they did not attend.”

If the authorities failed to address the concerns of the Indian law firms, he said they would be forced to knock on the doors of the Supreme Court.

Clarity is key here.